Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Petrograd, Russia, 1917 - A World on the Edge

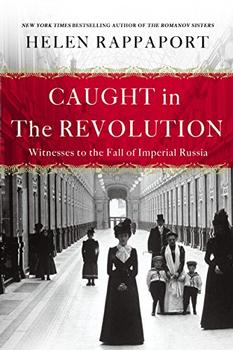

by Helen Rappaport

Embassy business struggled on, in the face of this mounting workload and predictions of imminent social breakdown. The first day of the Russian New Year, a day of intense cold, had been marked by a glittering reception for eighty members of the diplomatic corps in the ballroom of the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoe Selo. While US ambassador Francis – along with his nine members of staff – had eschewed the formal diplomatic paraphernalia of knee breeches, buckled shoes and plumed hats, choosing to wear a dress coat and wing collar, the rest of the diplomatic community travelled out in full rig, on the 'sumptuous' special train provided. From there they processed in sleighs laden with fur rugs through the swirling snow, past the frosted trees of the park, to the ringing of sleigh bells. All it needed was 'some baying wolves' to make it the classic Russian scenario, thought American diplomat Norman Armour. 'There this enchanted wonderland lay before our eyes,' wrote French diplomat Charles de Chambrun: 'The ornate façade of the palace stood waiting for its guests, illuminated by a thousand lights and surrounded by a semi-circle of whiteness.' Still, he wondered – as did many of his fellow diplomats – 'after all that had already happened, and all that people were saying, and all that was still brewing, how were we going to find the master of all this magnificence?'

'After shedding countless wraps' the assembled diplomats waited until the double doors to the red and gilded reception hall were thrown open by two tall Ethiopian guards in turbans and they were 'ushered into the most imposing room that I had ever seen, lined with endless gold mirrors and countless electric lights,' recalled J. Butler Wright. They were then arranged in groups in order of precedence, behind their 'dean', Sir George Buchanan, and his staff, when Nicholas II, simply dressed in a grey Cossack cherkeska, entered the room to greet them. During the course of the two-hour reception he conversed charmingly, with his usual smiles and handshakes, and in perfect English or French. 'He asked me how long I had been here, how I liked it, whether the cold was too severe and promised beautiful weather in the summer,' recalled Wright. Nicholas was a master of such empty pleasantries, but he became visibly uncomfortable when Sir George Buchanan seized the opportunity to impress upon him 'the necessity for a strong offensive on the Eastern Front to relieve pressure on the Western'. Norman Armour thought this inappropriate of the British ambassador on such a purely social occasion:'I watched as the Emperor twisted his astrakhan cap, displaying increased irritation as Buchanan talked on.'

Otherwise, the Tsar's responses in conversation were mundane, his eyes kindly but vacant. In the opinion of Charles de Chambrun, it was clear that he was 'not taking much interest in the replies'. Ambassador Francis, seduced by the Tsar's superficial charm, failed to notice his air of exhaustion: 'We were all impressed with the cordiality of His Majesty's manner, by his poise and his apparent excellent physical condition, as well as by the promptness of his utterances,' he noted in his diary.To his mind, the Tsar 'gave appearance of having supreme confidence in himself', so much so that he was happy to go off 'for a smoke' with US naval attaché Newton McCully and talk about 'the fall of Porfirio Diaz in Mexico' – rather than the state of Russia. But Wright, like his companion Armour, had thought Nicholas 'seemed very nervous and his hands fidgeted continually'. French ambassador Paléologue concurred: Nicholas's 'pale thin face' had 'betrayed the nature of his secret thoughts'.

All in all, it was an impressive gathering, of which much was made retrospectively by memoirists, Francis included, as marking 'the glitter and pomp of a dying era'. 'Little did any of us realize that we were witnessing the last public appearance of the last ruler of the mighty Romanoff dynasty,' he later wrote in his memoirs; the Tsar had seemed to have no idea that 'he was standing on a volcano'. Chambrun's overall impression was that Nicholas had looked 'more like an automaton needing winding up than an autocrat fit to crush all resistance'. A wider air of exhaustion and foreboding had been detected, too, by Ambassador Paléologue: 'among the whole of the Tsar's brilliant and glittering suite, there was not a face which did not express anxiety'. After enjoying the sherry and sandwiches and tipping the staff 'liberally', the diplomatic corps headed back to Petrograd. A few hours later Wright was drinking vodka and gorging himself on caviar and zakuski at Armour's flat on the Liteiny, to celebrate the New Year. In the days that followed,Wright enjoyed trips to the opera to see Tchaikovsky's Evgeniy Onegin, the ballet with Meriel Buchanan at a packed Mariinsky Theatre, bridge at Princess Chavchavadze's ('a rather brilliant gathering'), dinner at the Café de Paris and skating at an exclusive private club, where being a member of the diplomatic corps 'was always and everywhere an Open Sesame'. If the Tsar was standing on the edge of the volcano, then so too were most of the diplomatic community, along with the blinkered sybarites of Russian high society.

Excerpted from Caught in the Revolution by Helen Rappaport. Copyright © 2017 by Helen Rappaport. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A library is a temple unabridged with priceless treasure...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.