Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The engine drowns out everything, but I remember the sound of the power lines, the soft humming, in wet weather, water against electricity, a crackling. It has always given me goose bumps, especially in darkness, when you can see how it sparks.

All four of the moorings for visitors at the wharf are vacant. It's too early for tourists—the moorings are used only in the summertime, so I can take my pick. I choose the spot farthest out, mooring the craft astern and at the bow and put out a spring line to be on the safe side; the wind from the west could blow up without any warning. As I pull the throttle control completely astern, I can hear the reluctant gasps of the engine shutting down. I close the hatch to the saloon and place the bunch of keys in the breast pocket of my parka. The key ring is a big cork ball that ensures it will float—it produces a small bulge over my stomach.

The bus stop is where it has always been, outside the consumer co-op. I sit and wait—the bus comes only once an hour. That's how it is here; everything happens seldom and must be planned. I have just forgotten about it after all these years.

Finally it appears. I am accompanied by a group of adolescents. They come from the high school that was built in the early 1980s, the new one, the nice one, one of the many things the village could afford. They talk and talk about tests and homework assignments. I can't help but notice their smooth foreheads, soft cheeks; they are astoundingly young, without any marks whatsoever, without the traces of a life lived.

They don't even bother to glance at me. I understand them well. For them I am just an aging woman, a little shabby and unkempt in a worn-out parka, with gray locks of hair sticking out from beneath a knitted hat.

They have new, almost identical hats, with the same logo in the middle of the brow. I hasten to take off my own and put it in my lap. It is of course full of fuzz balls. I start picking them off one by one and my hand fills up with lint. But there's no point, there are too many of them to remove and now I don't know what to do with them, so I end up sitting there with a loose mound in my hand. Finally I release it down onto the floor. The wool floats weightlessly down the aisle, but the adolescents don't pay it any mind, and why should they look at a clump of gray lint?

Sometimes I forget how I look. After a while you stop caring about your appearance when you live on board a boat, but once in a great while when I see myself in a mirror on land, when the lighting is good, I am startled. Who is she, the person in there? Who in the world is that skinny old biddy?

It is strange—no, surreal, surreal is the word—that I'm one of them, the old people, when I am still so completely myself through and through, the same person I have always been. Whether I am fifteen, thirty-five, or fifty, I am a constant, unchanged mass. Like the person I am in a dream, like a stone, like one-thousand-year-old ice. My age is disconnected from me. Only when I move does its existence become perceptible—then it makes itself known through all its pains, the aching knees, the stiff neck, the grumbling hip.

But the young people don't think about my being old, because they don't even see me. That's how it is, nobody sees old ladies. It has been many years since a young person looked at me. They just laugh youthfully and openly and talk about a history quiz they've just taken, the Cold War, the Berlin Wall, what grades they got. And nobody mentions the ice, not a word about the ice, about the glacier, even though it should be what everyone is talking about here at home.

Here at home—do I really still call it home? I can't fathom it, after having been away for almost forty years—no, soon fifty years. I came home only to clean up after a death in the family, to grieve the compulsory five days after the funerals, first my mother's, then my father's. A total of ten days is all the time I have spent here during all these years. I have two brothers here, half brothers, but I hardly ever speak with them. They are my mother's boys.

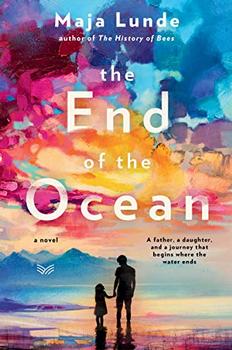

Excerpted from The End of the Ocean by Maja Lunde. Copyright © 2020 by Maja Lunde. Excerpted by permission of Harper Via. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Choose an author as you would a friend

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.