by Lisa Kaltenegger

For thousands of years, humans have wondered whether we're alone in the cosmos. Now, for the first time, we have the technology to investigate. But once you look for life elsewhere, you realize it is not so simple. How do you find it over cosmic distances? What actually is life?

As founding director of Cornell University's Carl Sagan Institute, astrophysicist Lisa Kaltenegger has built a team of tenacious scientists from many disciplines to create a specialized toolkit to find life on faraway worlds. In Alien Earths, she demonstrates how we can use our homeworld as a Rosetta Stone, creatively analyzing Earth's history and its astonishing biosphere to inform this search. With infectious enthusiasm, she takes us on an eye-opening journey to the most unusual exoplanets that have shaken our worldview - planets covered in oceans of lava, lonely wanderers lost in space, and others with more than one sun in their sky! And the best contenders for Alien Earths. We also see the imagined worlds of science fiction and how close they come to reality.

With the James Webb Space Telescope and Dr. Kaltenegger's pioneering work, she shows that we live in an incredible new epoch of exploration. As our witty and knowledgeable tour guide, Dr. Kaltenegger shows how we discover not merely new continents, like the explorers of old, but whole new worlds circling other stars and how we could spot life there. Worlds from where aliens may even be gazing back at us. What if we're not alone?

"We are living in an incredible time of exploration," says Alien Earths author Dr. Lisa Kaltenegger, and after reading her new book it's impossible to argue. Only in recent years have we developed the technology and skills to search other galaxies for exoplanets similar to Earth and examine them for signs of life. After all, the full title is Alien Earths: The New Science of Planet Hunting in the Cosmos, and planet scout Dr. Kaltenegger gives us exactly what we came for.

She offers insight into why our planet holds complex life to begin with, explaining a crucial elemental fusion. Earth exists within a galactic sweet spot, coined the Goldilocks zone by scientists — the perfect location in relation to the sun: not too hot (like Venus), not too cold (like Mars), and most importantly, able to hold liquid water. This is because "[L]ife on Earth is built on carbon scaffolding, and it uses water as its solvent (a powerful medium that dissolves substances). The abundance of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen in the universe means that life on other worlds, if it exists, is likely to be supported by water and carbon."

Dr. Kaltenegger herself is responsible for many advancements in the field. Early in her double career of astronomy and engineering, she was invited to Yellowstone National Park for a field study. There, she observed the array of colors indicating microorganisms within the famous geysers. She explains, "I realized that astronomers needed a color catalog of life — a database of diverse Earth biota and information on how they reflected incoming starlight — to compare to what our telescope would find on exoplanets." This experience led her to found the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell, gathering a team of scientists from fields far beyond astronomy to assist her in the hunt for cosmic life. Dr. Kaltenegger's excitement is tangible on every page of Alien Earths, as she guides readers through the universe and onto newly discovered star systems and exoplanets. (To learn about another exoplanet specialist, see our article on Sara Seager.)

The search was kicked off with the monumental Kepler mission in 2009. Harnessing a one-and-a-half-meter-long mirror, the telescope found habitable worlds by searching more than 150,000 stars at the same time. Kepler62 is one of the stars found, and it has two exoplanets, Kepler 62 e and Kepler 62 f, within the Goldilocks zone. Another star found is TRAPPIST1, which has seven Earth-sized planets, with three of them orbiting within the habitable zone: TRAPPIST 1 e, f, and g (although g is maybe a bit too cold for life). While an exoplanet orbiting within a Goldilocks zone shows it holds the capacity for life as we know it, scientists haven't discovered any just yet. There's also the chance that life could have evolved entirely differently somewhere else, in a way that is foreign to what we're used to — devoid of water and carbon, perhaps. Scientists continue to study these optimistic possibilities.

Though the Kepler mission could search far across the universe, scientists needed a different telescope that could search our closest star neighbors for exoplanets. Enter Dr. Kaltenegger's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) program. Once it was launched, using its "four seventeen-centimeter cameras, it searched the whole sky for tiny blips, tiny changes in the brightness of our closest stars." It has proven that every fifth star found has at least one rocky planet orbiting within its Goldilocks zone, which amounts to around three dozen exoplanets that "get about the same amount of light and heat from their stars as the Earth does from our sun."

Alien Earths is truly a pleasure to read — enlightening, compelling, and hopeful. The writing is woven with many scientific terms but is delivered in a highly digestible format. It reminds me of a quote attributed to Einstein: "If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough." Keeping this in mind, it's clear that Dr. Kaltenegger knows her stuff.

Marvelous and revelatory, Alien Earths will get you excited for our burgeoning, promising efforts to reach cosmic life on Earth-similar exoplanets. So much has already been learned in just a few decades, and we're only getting started. Thanks to Dr. Lisa Kaltenegger and her fellow scientists, we are closer than ever to meeting life on another planet. It's only a matter of patience, perseverance, and time.

Book reviewed by Christine Runyon

From the 17th century on, Johannes Kepler, Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, HG Wells, and Edgar Rice Burroughs were just a few artists who contributed to a burgeoning awakening of the collective imagination, melding scientific and cosmic theories with myth and character, shaping something entirely new — science fiction.

How science fiction evolved from simple stories into a huge pop culture phenomenon could be an article unto itself. But it's worth noting that in 1966, science fiction was transformed forever when Star Trek premiered on NBC. In the show, the Starfleet organization was conceived with the goal of exploring and learning from our neighboring galaxies in the universe. Sound familiar? As it turns out, NASA was heavily inspired by Gene Roddenberry's groundbreaking series, and this influence ripples through the past and present like the ridges on a Klingon's forehead.

So why do real-life scientists love Star Trek so much? The show was launched at a time when the United States was in the toddler stage of space exploration. Smithsonian Air & Space Magazine contributor Glen E. Swanson, who's also a former historian of the NASA Johnson Space Center, offers key context: "When the Apollo 1 tragedy occurred, people had been flying into space for less than seven years. Spaceflight was new and dangerous, and here was a show that made it feel routine. Star Trek offered hope to a nation and a space program in a moment when both had reason to doubt they would ever reach the moon, never mind the 'new life and new civilizations' promised in the show's opening-credits monologue."

Even the official NASA website formally acknowledges Star Trek's influence on their programs: "In the 2016 documentary 'NASA on the Edge of Forever: Science in Space,' host NASA astronaut Victor J. Glover states, 'Science and Star Trek go hand-in-hand.' The film explores how for the past 50 years, Star Trek has influenced scientists, engineers, and even astronauts to reach beyond their potential."

In 1977, when NASA needed a fresh set of astronauts to work on upcoming projects, they asked Nichelle Nichols, who played Lt. Uhura, to assist. The Star Trek actress went on a four-month long campaign for NASA, and even filmed a recruitment video (see below) urging women and minorities to apply. The following year, NASA hired a new crop of 35 astronauts, "for the first time including women and minorities."

Trekkies (or Trekkers — choose your nomenclature) know that Star Trek is an enjoyable tool for understanding ourselves and each other. Our failings and misunderstandings, possible solutions to societal problems — all are speculated and commented upon in Star Trek. It shows us the future could be optimistic and peaceful, on Earth and beyond. According to Gene Roddenberry, "It's a program that said there is basic intelligence and goodness and decency in the human animal that will triumph."

For scientists, Star Trek and other works of science fiction offer elements of intrigue for the perpetually questioning and searching mind. According to Dr. Lisa Kaltenegger's new book, Alien Earths, "Astronomy and science fiction can be a quirky, unusual, and entertaining part of life ... Most astronomers I know enjoy science fiction, sometimes questioning how to implement its finer plot points."

When your job revolves around investigating the existence of life on other planets, it only makes sense. Delving into sci-fi led astronomers to wonder if we might find planets and star systems like those we read about and watch on TV. In Alien Earths, fun connections are made to works in the genre, including Star Trek.

"The triple-star system 40 Eridani is about sixteen lightyears away from Earth and consists of a slightly smaller orange star (40 Eridani A), a white dwarf (40 Eridani B), and a red sun (40 Eridani C). In the Star Trek franchise, the planet Vulcan, the home world of commander Spock, circles 40 Eridani A."

The significance of Star Trek and other sci-fi like it cannot be overstated. A child obsessed with the genre may one day grow up to be a scientist destined for the stars, fueled by the big ideas seen on screen. Daring to dream the impossible, working to make it a reality.

by Leigh Bardugo

A MOST ANTICIPATED BOOK OF 2024 by The Washington Post, NPR, Goodreads, LitHub, The Nerd Daily, Paste Magazine, Today.com, and so much more!

In a shabby house, on a shabby street, in the new capital of Madrid, Luzia Cotado uses scraps of magic to get through her days of endless toil as a scullion. But when her scheming mistress discovers the lump of a servant cowering in the kitchen is actually hiding a talent for little miracles, she demands Luzia use those gifts to improve the family's social position.

What begins as simple amusement for the nobility takes a perilous turn when Luzia garners the notice of Antonio Pérez, the disgraced secretary to Spain's king. Still reeling from the defeat of his armada, the king is desperate for any advantage in the war against England's heretic queen―and Pérez will stop at nothing to regain the king's favor.

Determined to seize this one chance to better her fortunes, Luzia plunges into a world of seers and alchemists, holy men and hucksters, where the lines between magic, science, and fraud are never certain. But as her notoriety grows, so does the danger that her Jewish blood will doom her to the Inquisition's wrath. She will have to use every bit of her wit and will to survive―even if that means enlisting the help of Guillén Santángel, an embittered immortal familiar whose own secrets could prove deadly for them both.

Luzia, the heroine of Leigh Bardugo's novel The Familiar, is a young woman employed as a scullion in the home of the decidedly middle-class Marius and Valentina Ordoño. Although she appears to be just an ordinary servant, Luzia can perform simple magic — unburning a loaf of bread, fixing torn clothing, turning six eggs into a dozen. She does her best to keep this talent hidden; it's the age of the Spanish Inquisition, and she fears coming to the institution's attention, well aware that her gift would be viewed with mistrust. Making her situation even more precarious is that she's a "converso" (a Jew who's converted to Christianity) and would very likely end up being tortured and then burned at the stake if arrested. One day her mistress accidentally sees one of these "milagritos" — little miracles. Eager to improve her status, Valentina invites important people to dinner and forces Luzia to perform. As Luzia's fame spreads and her talent grows, she comes to the attention of wealthy and powerful men who intend to use her abilities to improve their status at the court of Philip II — ultimately putting her life in grave danger.

Bardugo's prose is lovely throughout, with lush descriptions that bring each scene to life:

"A woman had entered the ballroom. Her hair was smooth and so black it shone nearly blue. Her milky skin seemed to catch the candlelight so she glowed like a captured star. Her staid gown was black velvet and covered her completely, but it was so heavily embroidered with diamonds and metallic thread that it no longer looked black, but like quicksilver, sparkling beneath the chandeliers."

She brilliantly conjures up a sense of magical wonder while casting it against the menacing shadow of the Inquisition. It's this tension that drives the plot and keeps the pages turning.

The author's attention to historical detail is also superb. She completely captures the everyday life of the times (Luzia must walk to a fountain to get buckets of water, sleeps on a cellar floor and attends mass daily). Beyond that, many of the characters are real-life historical figures, including Lucrecia de León (see Beyond the Book), Antonio Pérez and Miguel de Piedrola. While none are major characters, they're inserted so skillfully that their inclusion feels like a natural outgrowth of the story.

The real highlight, though, is Bardugo's fictional characters and their development. I was especially impressed with the depth she gives each. We gradually learn, for example, that Luzia isn't as oblivious and obedient as she appears to be, and we come to understand why she takes the risks she does. Valentina, too, transforms in unexpected ways by the end. Each character, in fact, is imbued with complexity, and it's this intricacy that makes the novel such a winner.

The Familiar should be of interest to a young audience in addition to an older one with its emphasis on fantasy, both magical and romantic. It's a fun, fast read that reminded me of The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, and those who enjoyed that book will likely find this one equally enchanting. It will also appeal to historical fiction readers, especially those interested in Renaissance Spain, and it's sure to become a book club favorite.

Book reviewed by Kim Kovacs

The fictional heroine of Leigh Bardugo's novel The Familiar interacts with several characters based on people who really did live in Spain during the 16th century. One of these is a young woman based on the figure Lucrecia de León, also known as "Lucrecia the Dreamer." Like the main character Luzia, Lucrecia comes under government suspicion for having certain abilities that are not easily explained, a detail that is consistent with the facts of De León's life.

The fictional heroine of Leigh Bardugo's novel The Familiar interacts with several characters based on people who really did live in Spain during the 16th century. One of these is a young woman based on the figure Lucrecia de León, also known as "Lucrecia the Dreamer." Like the main character Luzia, Lucrecia comes under government suspicion for having certain abilities that are not easily explained, a detail that is consistent with the facts of De León's life.

Spain's ruler, Philip II, moved his court and imperial residence to Madrid in 1561, and by the end of the decade the city had become a hotbed of political intrigue. Conspiracies and rumors ran rampant and talk against the king was common. Many felt the monarchy had become corrupt and greedy, working for the benefit of the wealthy rather than its subjects. Prophecies were used as a tool to both validate the king's rule and to protest his policies.

Lucrecia de León was born into this environment in 1567 or 1568, the daughter of a solicitor of modest means who received little education. She had vivid dreams from an early age and could relate them in stunning detail. When some of the dreams came true, people started asking her to divulge her visions to them. She began charging a fee for the information, against her father's wishes.

As Lucrecia grew into adulthood, news of her talents reached the ears of a powerful clergyman, Alonso de Mendoza. Mendoza was obsessed with prophecies and arranged to have Lucrecia's dreams recorded regularly. Ultimately these "Dream Registers," compiled from November 1587 through April 1590, would contain over 400 entries.

Lucrecia ran afoul of the government in February 1588, when her dreams predicted the defeat of Spain's Armada, and the deaths of Philip and his son and heir. Her arrest was ordered by the vicar of Madrid. Mendoza appealed to the papal nuncio and the inquisitor general, asking for time to determine if Lucrecia's dreams were a gift from God. He prevailed and she was released, and the following August the Spanish Armada was, indeed, crushed as she had predicted. She consequently became even more popular.

During this same time, the king's secretary, Antonio Pérez, fell from favor. Once Philip's confidant, Pérez manipulated and deceived him; when this betrayal was discovered, Pérez was arrested. He escaped from prison in April 1590, with the help of a supporter who also championed Lucrecia, and she came under suspicion of plotting against the monarchy and supporting Pérez as a result.

She was questioned — sometimes under torture — for the next five years. She may have been held for so long because some of her visions had come true, and so some wondered if she was divinely inspired. The court finally issued a verdict in July 1595, convicting her of blasphemy, witchcraft and sedition, among other things. Her auto-da-fé — a public ritual of penance — was held five days later. She was sentenced to 100 lashes and imprisonment for two years, followed by permanent expulsion from Madrid. This was actually a light sentence, as many accused of such serious crimes were burned at the stake. There's no documentation as to why she was shown such leniency, although the authorities may have concluded she was just an ignorant girl who was used by unscrupulous enemies of the crown.

Lucrecia's ultimate fate remains unknown; she disappears from the historical record at this point.

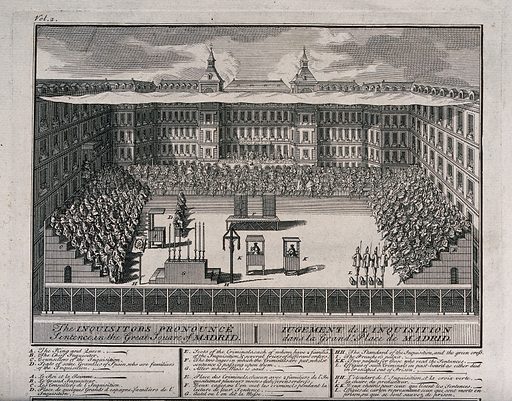

An auto-da-fé in the Great Square in Madrid

Illustration courtesy of Wellcome Collection via Look and Learn (CC BY 4.0)

by Amor Towles

Millions of Amor Towles fans are in for a treat as he shares some of his shorter fiction: six stories based in New York City and a novella set in Golden Age Hollywood.

The New York stories, most of which take place around the year 2000, consider the fateful consequences that can spring from brief encounters and the delicate mechanics of compromise that operate at the heart of modern marriages.

In Towles's novel Rules of Civility, the indomitable Evelyn Ross leaves New York City in September 1938 with the intention of returning home to Indiana. But as her train pulls into Chicago, where her parents are waiting, she instead extends her ticket to Los Angeles. Told from seven points of view, "Eve in Hollywood" describes how Eve crafts a new future for herself—and others—in a noirish tale that takes us through the movie sets, bungalows, and dive bars of Los Angeles.

Written with his signature wit, humor, and sophistication, Table for Two is another glittering addition to Towles's canon of stylish and transporting fiction.

Amor Towles's short story collection Table for Two reads as something of a dream compilation for those of us who have dearly wished we could spend just a bit more time in the company of his characters and in the fully imagined settings of his novels Rules of Civility (2011), A Gentleman in Moscow (2016) and The Lincoln Highway (2021). It appears that the author may have felt that way, too.

Although we get just a short whiff of the Moscow location of Towles's Gentleman in Moscow in "The Line," the first of six stories that make up the New York section of Table for Two, the general sensibility, gentle humor and expert storytelling we associate with Towles and, perhaps, his greatest character, Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, reverberate through all of the stories, particularly the wry first-person narrative of "The Didomenico Fragment." Here, retired art expert Percival Skinner recounts his attempt to broker the sale of a fragment of an important Italian Renaissance painting of the Annunciation. His family has increasingly mutilated the masterpiece, as each successive generation has cut it into smaller pieces to pass down equal sections to their children in an ever-shrinking inheritance. This is only one element of the story, but it demonstrates how Towles can present us with an absolutely absurd proposition in such a reasonable manner that we don't even blink as we easily visualize the dwindling artifact. In this story, as in others in the volume, readers are kept engrossed by one surprising plot twist after another; Guy de Maupassant would be proud.

The second, and perhaps more satisfying, Los Angeles section of the book contains the novella "Eve in Hollywood," which serves as a sequel of sorts to Rules of Civility and reintroduces the intrepid character Eve Ross, now busy creating a new life for herself in late-1930s Hollywood. (I will note here that the novella stands alone and will still appeal to readers who have not read Rules.)

We last heard of twenty-something Eve at the end of Rules of Civility when she left New York still reeling from a series of traumatic events. Readers were told that, on the way to her parents' midwestern home, she suddenly changed her mind and extended her train ticket to Los Angeles. Later, she was glimpsed in a photograph from a gossip magazine in the company of a "boisterous Olivia de Havilland." From these two small pieces of information, Towles has constructed his novella.

Eve ends up at the elegant Beverly Hills Hotel, where she gathers a small collection of wonderful, eccentric friends, including the charming young actress de Havilland, who has just completed her role starring as Maid Marian opposite Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood. The reader will be forgiven for again thinking of the Metropole Hotel setting of A Gentleman in Moscow. There is something about a grand hotel that Towles just can't seem to resist, and thank goodness for that. But instead of the grey Moscow skyline, Towles now harnesses the evocative setting of Los Angeles in the years just before the Second World War when Hollywood was at its peak of glamour and the jasmine-scented air felt ripe with possibility.

Of course, one can't write about Los Angeles of this period without giving a nod to the great LA writers of the era, particularly Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, and Towles includes an exciting mystery subplot in which Eve gets to the bottom of a blackmailing scheme using nothing but brains, clever repartee, friends with the right skills and a surprisingly handy recipe for concocting a drug-laced Micky Finn to knock out the baddies.

The introduction of real people into the mix, such as Olivia de Havilland and the film executive Jack Warner (see Beyond the Book), works wonders to establish a strong sense of time and place, as does the snappy dialogue that feels straight out of the mouths of Nick and Nora Charles in any of the Thin Man films. In all this is a delightful group of stories to dive into, and Towles will not disappoint any of his admirers.

It should be noted that as is often the case with story collections, several of the stories have previously appeared elsewhere. I distinctly remember sitting on an airplane some years ago listening to an Audible Original recording of "The Didomenico Fragment," read by the great John Lithgow, and an earlier version of "Eve in Hollywood" was published as a Penguin special edition. But regardless of the stories' publication history, readers will still appreciate having them in a single volume for the first time.

Book reviewed by Danielle McClellan

In the novella "Eve in Hollywood," in Amor Towles's Table for Two, Eve Ross becomes close friends with the actress Olivia de Havilland. It is 1938, and De Havilland's popular new film The Adventures of Robin Hood has just been released. All is not well in paradise, however, for the young star falls prey to blackmailers, even as she struggles to wrest more control over her career from a paternalistic Hollywood studio. While the first plot point is pure fantasy, the second, in fact, accurately reflects the real Olivia de Havilland's struggles with the Hollywood studio system.

Olivia de Havilland (b. 1916) and her younger sister Joan (b. 1917, later known as the actress Joan Fontaine) were born in Japan to British parents, but grew up in the California town of Saratoga. After high school, a teenage De Havilland was cast as second understudy for the role of Hermia in a splashy Hollywood Bowl staging of A Midsummer Night's Dream, produced by Max Reinhardt. When both the actress playing Hermia and the first understudy dropped out only one week before the play's premiere, De Havilland stepped into the plum role. In the subsequent film version Reinhardt made for Warner Bros., he again cast De Havilland as Hermia.

In November 1934, De Havilland signed a standard seven-year contract with Warner Bros., with a starting salary of $200 a week (about $4,600 today). De Havilland entered the film business during a period known as the golden age of the Hollywood studio system. Its five major studios—Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM), RKO, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures—followed a business strategy known as vertical integration through which "they owned all aspects of production, distribution, and exhibition," according to writer Mike Maher. "From before cameras started rolling until the theaters projectors stopped, the entire process was controlled by the studios." And for contracted actors, powerful executives dictated all aspects of life, including molding their public image and deciding which roles they would take.

In the first year of her contract, Warner Bros. cast 18-year-old De Havilland to star with 25-year-old actor Errol Flynn in the action-adventure film Captain Blood. Flynn and De Havilland would go on to make several films together, the most popular being The Adventures of Robin Hood. Although these films did well at the box office, De Havilland began to grow frustrated with the characters she was playing. In an interview, De Havilland explained: "The life of the love interest is really pretty boring.…The heroine has nothing much to do, except encourage the hero…. I longed to play a character who initiated things, who experienced important things, who interpreted the great agonies and joys of human experience. I certainly wasn't doing that on any level."

In the first year of her contract, Warner Bros. cast 18-year-old De Havilland to star with 25-year-old actor Errol Flynn in the action-adventure film Captain Blood. Flynn and De Havilland would go on to make several films together, the most popular being The Adventures of Robin Hood. Although these films did well at the box office, De Havilland began to grow frustrated with the characters she was playing. In an interview, De Havilland explained: "The life of the love interest is really pretty boring.…The heroine has nothing much to do, except encourage the hero…. I longed to play a character who initiated things, who experienced important things, who interpreted the great agonies and joys of human experience. I certainly wasn't doing that on any level."

In December of 1938, De Havilland got a call from George Cukor, who was preparing to direct the film Gone with the Wind for David Selznick and MGM. He asked her if she would be interested in playing the coveted role of Melanie Hamilton. She was thrilled at the opportunity, but her contract required her to get permission from Warner Bros.'s infamously hard-nosed executive, Jack Warner. She later recalled that Warner "utterly refused to lend me for Melanie…. I even went to call on him and begged him. He said, no." Desperate, De Havilland made a bold move. She called Warner's wife, Ann, herself a former actress, and asked her to help: "Through her, Jack eventually agreed." The film became an instant classic, and De Havilland received a best supporting actress Oscar nomination.

In 1943, just as De Havilland looked forward to the end of her contract with Warner Bros., the studio announced that they would not release her until she had repaid them for time lost by her previous contract suspensions with another film. This was business as usual for big studios, which punished actors who rejected assigned roles by extending the length of their contract for the time it took another actor to complete the role. De Havilland sued Warner Bros., arguing that "the contract was for seven years, suspension or not, and that Warner Bros. was violating labor law." This led to a difficult, drawn-out trial in which Warner lawyers goaded her to make her look unreasonable. The strategy backfired. The court ruled in her favor, declaring that "the actress's contract was a form of 'peonage' or illegal servitude." The actress not only won her case but saw it become a landmark judgment still known as the "De Havilland law." Many think this marked the beginning of the end for the Hollywood studio system, which, in 1948, was forced in a major anti-trust decision to begin dismantling vertical integration.

Although Warner Bros. tried to ruin de Haviland's career, she persevered, achieving greater fame and eventually capturing two Academy Awards. However, as film professor Jeanne Basinger comments, "Other actresses have won Academy Awards. Other stars have been as famous. But few had as far-reaching an impact as De Havilland did," thanks to her stellar performance under a different spotlight in a court of law.

Olivia de Havilland and Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood trailer, courtesy of Warner Bros.

by Paul Alexander

In the first biography of Billie Holiday in more than two decades, Paul Alexander—author of heralded lives of Sylvia Plath and J. D. Salinger—gives us an unconventional portrait of arguably America's most eminent jazz singer. He shrewdly focuses on the last year of her life—with relevant flashbacks to provide context—to evoke and examine the persistent magnificence of Holiday's artistry when it was supposed to have declined, in the wake of her drug abuse, relationships with violent men, and run-ins with the law.

During her lifetime and after her death, Billie Holiday was often depicted as a down-on-her-luck junkie severely lacking in self-esteem. Relying on interviews with people who knew her, and new material unearthed in private collections and institutional archives, Bitter Crop—a reference to the last two words of Strange Fruit, her moving song about lynching—limns Holiday as a powerful, ambitious woman who overcame her flaws to triumph as a vital figure of American popular music.

In 1958, Billie Holiday began work on an ambitious album called Lady in Satin. Accompanied by a full orchestra for the first time in her career and nervous, she was often late to rehearsal, drunk, or both. However, no amount of alcohol could make her voice blend seamlessly with the orchestra. After the album's release, critics unleashed their disappointment in striking fashion even as the public loved what she delivered. The Kansas City Star downgraded her voice, saying it "isn't what it used to be." The Los Angeles Times was more direct in their analysis, calling the album "sad," while the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Lady in Satin was "a [disturbing] experience for those who heard her when she was really singing."

Journalist Paul Alexander explains what the critics missed. "All the suffering, all the heartache was reflected in the damaged, tortured voice captured on the album." In his biography Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday's Last Year, he characterizes the aged musician as vocally weak yet popular and revered, loved by many, but not, perhaps, by herself.

Billie Holiday was an important figure in my house. She was the first black singer to be popularized in the era of Jim Crow, but more importantly, she owned a deep racial conscience. She once said, "I'm proud of those two strikes [being a woman and black]. I'm proud of being a Negro." Despite her popularity, she was not spared the indignities of Jim Crow prejudice; anti-black racism amplified her scars and triggered her vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, her influence was so significant Frank Sinatra valorized her accomplishments: "[She] still remains the greatest single musical influence on me." Lady Day, as she was first called by saxophonist Lester Young (almost immediately thereafter everyone in the industry referred to her as "Lady"), was celebrated by audiences whenever she took the stage in her floor-length glittery evening gown, belting out tunes in her haunting voice.

She was born Eleanora Fagan in Philadelphia in 1915. Her father, Clarence Holiday, was an immature adolescent who abandoned his responsibility, so Eleanora was raised by her mother Sadie, a housekeeper. At the age of ten, Eleanora was raped by a man named Wilbert Rich, her neighbor. Sadie interrupted the assault and called the police but Rich only served three months in jail.

To honor her father and her favorite actress Billie Dove (the stage name of Lillian Bohny), Eleanora changed her name to Billie Holiday. Her first singing gig was at a cabaret jazz club called Pod's and Jerry's. A columnist noticed her right away. "She was then about fifteen. She was dressed in a skirt and sweater, and she was barefoot. People gave her quarters and change to sing requests." Her first recording session was with Benny Goodman, who had never recorded with a Negro musician. She remembered, "I got there and I was afraid to sing in the mic because I never saw a microphone before…I was scared to death of it."

Café Society opened in 1938 in Greenwich Village and hired Billie as its headliner. Thrilled, she had no idea when she began performing there that she was under surveillance by the FBI because of her popularity and communist ties, which led to her being pursued and arrested on drug charges. She later wrote, "[M]y life has been made miserable. These people have dogged my footsteps from New York to San Francisco and all the territory in between."

She was appropriately fearful of being arrested again and coped by seeking the company of immoral and violent loser men, who didn't spare an opportunity to demean her, steal her money, or enable her drug use. What was tragic was not the male toxicity she was exposed to in itself but the desperate circumstances behind her allowance of it. She wanted to be a mother but adoption agencies turned her down because of her criminal record. The men she chose therefore became an ideation of her maternal fantasies. She took their abuse. She abused herself. Rinse. Repeat. The children were never born.

Billie's relevance returns annually whenever "Strange Fruit" (see Beyond the Book) is either sung or discussed during Black History Month. Nearly seventy years after her death, this points to her longevity in pop culture circles, a rarity for a jazz singer. "Strange Fruit" is her best-selling song and Alexander devotes an entire chapter to its rich history. His stirring prose evokes a camera following Billie all over the world. Billie at the Blue Note. Billie at the Monterey Jazz Festival. Billie at the Chatterbox Musical Bar.

"No matter what the motherfuckers do to you, never let them see you cry" is one of my favorite Billie quotes resurrected in this biography because of the perception it creates, that Billie Holiday was confident — and she was at times. But her insecurities were pronounced. Male abandonment beginning with her father, whose name she carried, triggered self-loathing that drugs, alcohol, and violent men only exaggerated. The aggressive and continued harassment of government agencies until her death affected her. She once told Parisian friends she was going to die between two cops, a sort of joke. But not a joke.

Here's something to understand about Alexander's biography of Billie: He isn't in awe of her, and therefore treats her like one would the non-famous if they earned the right to a public biography. As Oscar Wilde said, "be yourself, everyone else is already taken," and Billie is herself in Alexander's biography. But here's where my mind drifted. I thought of the Japanese art of kintsugi, in which broken pottery is repaired with a layer of gold dust. If only that could apply to the human soul, to someone like Billie. Painting gold over her deep scars as relief. But that would be reductive and miss the essence of Lady Day.

Her signature look was a white gardenia tucked behind her ear and it made a memorable statement for nearly three decades. When her voice was gone, the flower disappeared too. As if she knew the gardenia no longer fit her life. A more appropriate choice at this point would have been a yarrow: A cluster of small white blooms that survives in neglect, that is resilient and a beautiful color.

Book reviewed by Valerie Morales

In February 1959, Billie Holiday sang the anti-lynching song she popularized, "Strange Fruit," on the London television show Chelsea at Nine. She was battling liver disease because of a prodigious vodka and gin addiction. It was rare for Billie to sing "Strange Fruit" when she was this physically fragile.

"She just needed a reason to sing it," notes journalist Paul Alexander, author of Bitter Crop: The Heartache and Triumph of Billie Holiday's Last Year.

As Billie was known to do, she exaggerated the facts that night, telling the London audience it was a song written just for her. It wasn't.

"Strange Fruit" began as a poem titled "Bitter Fruit." It was written by a Russian Jew named Abel Meeropol, a Harvard University alum who taught high-school English in the Bronx. Meeropol was a member of the Communist Party beginning in 1932 and a writer whose pen name was Lewis Allan, taken from the names of his stillborn children. Like many communists, Meeropol believed strongly in racial equality. One day, as he was perusing a civil rights magazine, he came across a photograph of a lynching party that made him sick to his stomach. Lynching, the people who were responsible for its entrenchment, and those who profited from it centered his rage.

The photograph was taken in Marion, Indiana by a man named Lawrence Beitler. Hanging from trees were two innocent black teenagers, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, who had been accused of raping a white woman. Meeropol was emotionally overwrought after seeing the photograph and began writing. The poem "Bitter Fruit" was published in a teaching journal, and later he decided to turn it into a song that was then sung at leftist meetings, often by Meeropol's wife Anne. A black woman named Laura Duncan sang it in 1938 at Madison Square Garden. But Meeropol wanted a larger audience. He knew the owner of the Greenwich Village jazz club Café Society and trusted him.

The lyrics are haunting: Southern trees bear a strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/Black body swinging in the Southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees/Pastoral scene of the gallant South/The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth/Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh/And the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Right before Billie sang "Strange Fruit" for the first time, everything in Café Society quieted to a hush. The waiters and busboys were noiseless figures along the wall. The lightless room with only her face drowning in a pearly light was oddly melodramatic but appropriate considering the lyrics. Billie sang the song with her eyes closed, as if visited by the lynched, as if they were her father and brother. By the end, tears were streaming from eye to chin. When she finished, according to biographer David Margolick, "the lights went out, she was to walk off the stage, and no matter how thunderous the ovation, she was never to return for a bow."

She wanted to record the song. Her record company, Columbia Records, refused but allowed her to record it elsewhere as a compromise. After its release, the black newspaper The New York Age wrote that "Strange Fruit" was "believed to be the first phonograph recording in America of a popular song that has lynching as its theme." Time magazine said it was "a prime piece of musical propaganda" with "grim and gripping lyrics." Many consider "Strange Fruit" the symbolic start to the civil rights movement.

Although radio stations refused to play "Strange Fruit," it sold ten thousand copies its first week of release and reached number 16 on the popular charts.

Twenty years later on Chelsea at Nine, there Billie Holiday was in a sparkly gray dress and high-heeled shoes. She sang "Strange Fruit" impressively considering her illness. Her voice was mournful and vibrant and at the song's end — here is a strange and bitter crop — she was frozen in place as the applause echoed in her ears. She had leaned into the lyrics as if telling a painful story about her own sad life and her narration was stirring. As the audience cheered, she may have had no inkling of sand running through the hourglass. Time was fleeting. This would be the last time Lady Day was seen on television, After the performance, she went to a party to celebrate her appearance and later left London in a pleasant mood. Three months later, the famous Billie Holiday would be dead.

But "Strange Fruit" was for the ages. Time magazine, who had once labeled the song propaganda, in 1999 called it the "song of the century."

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.