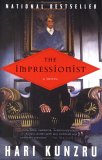

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Pran Nath

One afternoon, three years after the beginning of the new century, red dust that was once rich mountain soil quivers in the air. It falls on a rider who is making slow progress through the ravines that score the plains south of the mountains, drying his throat, filming his clothes, clogging the pores of his pink perspiring English face.

His name is Ronald Forrester, and dust is his specialty. Or rather, his specialty is fighting dust. In the European club at Simla they never tire of the joke: Forrester the forester. Once or twice he tried to explain it to his Indian subordinates in the Department, but they failed to see the humor. They assumed the name came with the job. Forester Sahib. Like Engineer Sahib, or Mr. Judge.

Forrester Sahib fights the dust with trees. He has spent seven years up in the mountains, riding around eroded hillsides, planting sheltering belts of saplings, educating his peasants about soil conservation, and enforcing ordinances banning logging and unlicensed grazing. Thus he is the first to appreciate the irony of his current situation. Even now, on leave, his work is following him around.

He takes a gulp from a flask of brackish water and strains in the saddle as his horse slips and rights itself, sending stones bouncing down a steep, dry slope. It is late afternoon, so at least the heat is easing off. Above him the sky is smudged by blue-black clouds, pregnant with the monsoon that will break any day. He wills it to come soon.

Forrester came down to this country precisely because it has no trees. Back at his station, sitting on the veranda of the Government Bungalow, he had the perverse idea that treelessness might make for a restful tour. Now he is here he does not like it. This is desolate country. Even the shooting is desultory. Save for the villagers' sparse crops, painstakingly watered by a network of dykes and canals, the only plants are tufts of sharp yellow grass and stunted thorn bushes. Amid all this desiccation he feels uncomfortable, dislocated.

As the sun heats up his tent in the mornings, Forrester has accelerated military-march-time dreams. Dreams of trees. Regiments of deodars, striding up hill and down dale like coniferous redcoats. Neem, sal, and rosewood. Banyans that spawn roots like tentacles, black foliage blotting out the blue of the sky. Even English trees make an appearance, trees he has not seen for years. Oddly shaped oaks and drooping willows mutate in lockstep as he tosses and turns. The dreams eject him sweating and unrested, irritated that his forests have been twisted into something agitated, silly. A sideshow. A musical comedy of trees. Even before he has had time to shave, red rivulets of sweat and dust will be running off his forehead. He has, he knows, only himself to blame. Everyone said it was a stupid time of year to come south.

If asked, Forrester would find it difficult to explain what he is doing here. Perhaps he came out of perversity, because it is the season when everyone else travels north to the cool of the hills. He has spent three weeks just riding around, looking for something. He is not sure what. Something to fill a gap. Until recently his life in the hills had seemed enough. Lonely, certainly. Unlike some, Forrester talks to his staff, and is genuinely interested in the details of their lives. But differences of race are hard to overcome, and even at the university he was never the social type. There was always a distance.

More conventional men would have identified the gap as woman shaped, and spent their leave wife hunting at tea parties and polo matches in Simla. Instead Forrester, difficult, taciturn, decided to see what life was like without trees. He has found he does not care for it. This is progress, of a sort. To Forrester, the trick of living lies principally in sorting out what one likes from what one does not. His difficulty is that he has always found so little to put on the plus side of the balance sheet. And so he rides through the ravines, a khaki-clad vacancy, dreaming of trees and waiting for something, anything, to fill him up.

Reprinted from The Impressionist by Hari Kunzru by permission of Dutton, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Hari Kunzru. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.