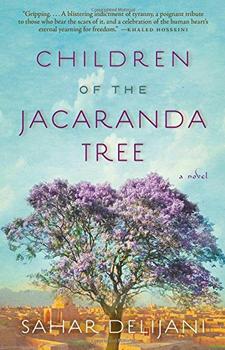

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Children of the Jacaranda Tree

Children of the Jacaranda Tree plants its story firmly in the tumultuous landscape of Iran in the 1970s and '80s. The Shah was overthrown in the late 1970s, and political activists were full of hope for a new kind of Iran. But it was to be a fleeting hope. The new Islamic Republic of Iran threw dissenters in prison, charging them with anti-government activities. Then, in 1988, they executed many of them.

Sahar Delijani, author of Children of the Jacaranda Tree, was born in Evin prison in Tehran, Iran's capital city, in 1983. Her parents had been among the many working to overthrow the monarchy. They were secularists who wanted and hoped for a secular republic, but instead the Islamic fundamentalists grabbed complete power and Iran became a theocracy. Many of the secular activists renewed their efforts for a democratic government and many of them ended in prison - including Delijani's parents and some of her aunts and uncles. Both Delijani's mother and aunt were pregnant at the time. Both gave birth in the prison.

Says Delijani:

"The book's first chapter is inspired by what my mom went through giving birth to me behind bars. A few years later my parents were released, which was fortunate for them because in 1988 - the last year of the Iran/Iraq war - the regime carried out mass executions of political prisoners. It has been estimated that the purge killed between three and twelve thousand people. We'll never know the exact number because their bodies weren't turned over to their families and funerals were not allowed. Instead many of the victims were buried in mass graves. My dad's brother was among those executed that summer."

Evin prison (nicknamed Evin University because it has held so many intellectuals) is located in Evin, in the north-west of Tehran, at the foot of the Alborz Mountains. Constructed in 1972, it has an execution yard, a courtroom, and cell blocks. It was originally run by the Shah's security and intelligence unit and was designed to hold 320 prisoners (20 in solitary and 300 in general); but was later expanded to house over 1500, including over 100 solitary cells for political prisoners.

Evin prison (nicknamed Evin University because it has held so many intellectuals) is located in Evin, in the north-west of Tehran, at the foot of the Alborz Mountains. Constructed in 1972, it has an execution yard, a courtroom, and cell blocks. It was originally run by the Shah's security and intelligence unit and was designed to hold 320 prisoners (20 in solitary and 300 in general); but was later expanded to house over 1500, including over 100 solitary cells for political prisoners.

After the Islamic Republic was established, Evin prison was expanded enormously – to house over 15,000 prisoners. While its stated purpose is as a detention center prior to trial, many prisoners have lived out their sentences in Evin, and many others have been executed there.

Internationally, Evin prison is synonymous with political prisoner and revolution. Many famous political activists and accused activists have been imprisoned – and worse – there. Here is a very small sampling of their stories:

Nargess Eskandari-Grünberg, an Iranian psychotherapist and current member of the Green Party in Germany, was imprisoned at Evin after demonstrating for women's rights and reform. She says that prisoners don't have a good sense of what the prison looks like because they are blindfolded when moving from place to place. Torture is a standard practice for interrogation.

Activist Marina Nemat was arrested and imprisoned in 1982 for attending rallies and writing anti-revolutionary articles in her school newspaper against the Iranian Republic. She was 16 years old, and was sentenced to life. But in a remarkable turn of fate, a prison guard fell in love with her and forced her to marry him, which allowed her to leave the prison. After he died she was sent back and it was his family that ultimately helped her get released for good.

Activist Marina Nemat was arrested and imprisoned in 1982 for attending rallies and writing anti-revolutionary articles in her school newspaper against the Iranian Republic. She was 16 years old, and was sentenced to life. But in a remarkable turn of fate, a prison guard fell in love with her and forced her to marry him, which allowed her to leave the prison. After he died she was sent back and it was his family that ultimately helped her get released for good.

Akbar Ganji, an Iranian journalist and writer was held in Evin from 2001-2006 after publishing stories about dissident writers who had been assassinated. He has been called Iran's preeminent dissident. Mohsen Sazegara, also an Iranian journalist and pro-democracy activist, was imprisoned in 2003. Nasser Zarafshan, an Iranian novelist, translator, and attorney, was at Evin from 2002-2007 because he was legal counsel for two of the families that Ganji had written about.

Akbar Ganji, an Iranian journalist and writer was held in Evin from 2001-2006 after publishing stories about dissident writers who had been assassinated. He has been called Iran's preeminent dissident. Mohsen Sazegara, also an Iranian journalist and pro-democracy activist, was imprisoned in 2003. Nasser Zarafshan, an Iranian novelist, translator, and attorney, was at Evin from 2002-2007 because he was legal counsel for two of the families that Ganji had written about.

Roxana Saberi, an Iranian-Japanese journalist, was arrested on accusations that she was a spy. She explains that intimidation and isolation are common confession techniques; that she was forced to confess to things that weren't true; that she was given no pen and paper, no bed, and had to ask to go to the bathroom.

Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian photojournalist, was taken into Evin prison in 2003 after being arrested for taking photos of a student protest outside a prison in Tehran. She died of trauma to the head after being beaten and raped shortly after entering Evin.

Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian photojournalist, was taken into Evin prison in 2003 after being arrested for taking photos of a student protest outside a prison in Tehran. She died of trauma to the head after being beaten and raped shortly after entering Evin.

Tens of thousands of activists have entered Evin; many thousands have died there. Children of the Jacaranda Tree gives voice to them, as well as their children.

Says Delijani:

Says Delijani:

"I want readers to see that history is the same all over the world. We all want the same things. Every nation has had its wars, its own fight for democracy, and its own battles for freedom. Whether these battles take place in Syria, Argentina, Burma, Iran or anywhere else they're all similar and all carry the same message: that people want to live freely; that we are all much more alike than we could possibly imagine; that we all want the same things; and we all go through the same pain to get there. Anyone who has given birth in a prison and ends up having to give their child away goes through the same grief and the same pain, regardless of what country they're from. That's the overriding message: we're all the same."

First portrait of Marina Nemat, second of Mohsen Sazegara, third of Zahra Kazemi and the final portrait of Sahar Delijani.

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Children of the Jacaranda Tree. It originally ran in July 2013 and has been updated for the

June 2014 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Children of the Jacaranda Tree. It originally ran in July 2013 and has been updated for the

June 2014 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Sometimes I think we're alone. Sometimes I think we're not. In either case, the thought is staggering.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.