Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

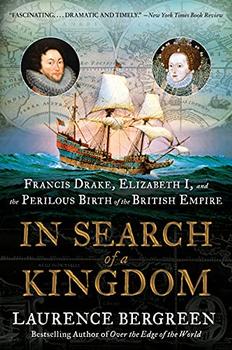

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence BergreenThis article relates to In Search of a Kingdom

In the United States, the term "colonies" typically conjures images of pilgrims eking out homesteads and log cabins in the woods, or soldiers in tri-cornered hats fighting the mighty British at the birth of the American republic. Yet, the colonization of the "New World," as Europeans called it, began well before these early settlements in New England. Starting with Columbus's initial voyage, colonization of the Americas was driven by Spanish and Portuguese economic forces, eventually drawing in most European nations and West African polities, with cataclysmic consequences for people around the world.

The quest for gold was always a primary goal for the early European explorers, and with the conquest of the Aztecs in 1519, Hernán Cortés began the transfer of incredible amounts of wealth from the New World back to the Old. In the 1530s, Francisco Pizarro overran the Incas and shortly thereafter, the Spanish found Potosí, a mountain in modern-day Bolivia that was overflowing with veins of silver. It's estimated that from the 16th to the 17th centuries, 40,000 tons of silver made its way from Potosí to Europe.

But mining for silver and gold required labor, and it came at an unimaginable cost to the people involved. The Spanish colonial forces enslaved entire communities and civilizations to build their mining workforce across Mexico and South America. The hellish conditions led to massive casualties, decimating even further the Indigenous populations that had been slaughtered in conquest and annihilated by diseases for which they had no immunity. The repercussions for these populations were catastrophic, yet the wealth continued to fuel global trade and European political rivalries for centuries.

In the 1570s, gold and silver from the Americas made Spain the preeminent powerhouse of Europe, and England under Queen Elizabeth I eyed their trade in Asia, funded by American bullion, with envy. Elizabeth supported the clandestine piracy of Francis Drake, resulting in truly a king's ransom in stolen wealth, and English interest in the American colonies continued to grow. But it wasn't direct conquest of the mines in Mexico or Potosí that they sought. Rather, British citizens began establishing plantations in the Caribbean, where another commodity — sugar — had been introduced by Spanish colonizers.

In the 1570s, gold and silver from the Americas made Spain the preeminent powerhouse of Europe, and England under Queen Elizabeth I eyed their trade in Asia, funded by American bullion, with envy. Elizabeth supported the clandestine piracy of Francis Drake, resulting in truly a king's ransom in stolen wealth, and English interest in the American colonies continued to grow. But it wasn't direct conquest of the mines in Mexico or Potosí that they sought. Rather, British citizens began establishing plantations in the Caribbean, where another commodity — sugar — had been introduced by Spanish colonizers.

Initially, the British shipped captives of European wars to labor on sugar plantations on Barbados, Jamaica and other Caribbean islands. The wholesale extermination of the Indigenous population by previous Spanish colonizers meant that labor had to come from somewhere else. But, as the European workers perished in large numbers in the punishing conditions, the British turned to importing African people as slaves instead. The Royal African Company was established in 1672 to supply slaves for the Caribbean plantations, but by the early 18th century, merchants were eager to end the company's monopoly on the slave trade and cash in themselves. "With alluring incentives spurring private enterprise, the volume of the slave trade increased dramatically," explains Vincent Brown, in his history of the Atlantic slave trade Tacky's Revolt. "For example, Jamaica alone received nearly four times the number of human cargoes in 1729 as it had in 1687."

It wasn't only sugar, of course, but also tobacco, rice and cotton grown in the North American colonies that drove the extensive slave trade into the 19nth century. This trade ensnared millions of African people and fueled cycles of violence among African states along the western coast of the continent, including Oyo, Dahomey and Asante. Trading captives for guns, these "predatory slaving states proliferated and gathered strength in the eighteenth century, and the privations and chaos attending their local wars made ever more refugees available for capture and sale abroad," according to Brown.

Taken together, the colonization of North and South America drove these demographic disasters, from the destruction of Indigenous populations to African slavery. And, while the western world is still struggling with how to address this part of its history and the legacy it left behind, the need to honestly reckon with the scale of the upheaval remains a central place to begin.

Painting from Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823) by William Clark

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to In Search of a Kingdom. It originally ran in April 2021 and has been updated for the

March 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to In Search of a Kingdom. It originally ran in April 2021 and has been updated for the

March 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.