Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

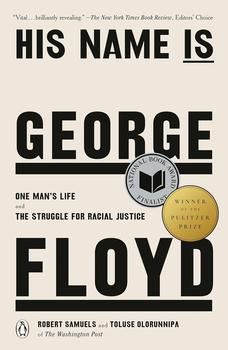

One Man's Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice

by Robert Samuels, Toluse OlorunnipaThis article relates to His Name Is George Floyd

In His Name Is George Floyd, authors Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa explain how Floyd's ancestors were dispossessed of their lucrative North Carolina farmlands via shady financial documents and restrictions on their literacy rendering them unable to read those very documents. This is just one example of the reassertion of white supremacy following the post-war period known as Reconstruction, and it fits into a larger pattern of discrimination that accompanied the collapse of government efforts to enfranchise and protect formerly enslaved people.

At the close of the Civil War, Congress passed a series of Constitutional amendments and other legislation that established equal rights for newly emancipated Black Americans. Reconstruction, which lasted from 1865 to 1877, "saw the greatest expansion of human and civil rights ever witnessed in this nation," as Nikole Hannah-Jones explains in The 1619 Project. The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, outlawed slavery; the 14th, ratified in 1868, provided citizenship to everyone born in the United States as well as equal protection under the law; and the 15th, ratified in 1870, enshrined the right to vote for all men regardless of skin color. In addition, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 outlawed housing discrimination and ensured rights such as inheriting property.

In those years, Black men were elected to Congress and state and local legislatures, and compulsory public schooling was established in the South for Black and white students alike. The presence of federal troops stationed in the former Confederacy oversaw this expansion of rights and opportunities, but once these checks on white supremacist retribution were removed, rights for formerly enslaved people were systematically dismantled.

"For the fleeting moment known as Reconstruction," Hannah-Jones writes, "the majority in Congress, and the nation, seemed to embrace the idea that out of the ashes of the Civil War, we could birth the multiracial democracy that Black Americans envisioned, even if our founding fathers had not. But it would not last."

The catalyst was the election of 1876, which had no clear winner. A congressional Electoral Commission was formed, and in 1877, Rutherford B. Hayes struck a deal with Southern Democrats to grant him the presidency if he removed federal troops from the South, an agreement he promptly made good on. "The many gains of Reconstruction were met with widespread and coordinated white resistance, including unthinkable violence against the formerly enslaved, wide-scale voter suppression, electoral fraud, and even, in extreme cases, the violent overthrow of democratically elected biracial governments," Hannah-Jones explains.

Southern states swiftly enacted "Black Codes," which were re-named versions of antebellum slave codes. As Leslie Alexander and Michelle Alexander note in their essay "Fear" in The 1619 Project, these codes reestablished segregation in schools and public spaces: "Vagrancy laws were adopted and selectively enforced against Black people; these essentially made it a criminal offense not to work, often forcing formerly enslaved people to sign labor contracts with the same people who had once enslaved them." They also resulted in convict leasing laws that instituted a thinly veiled version of slavery, along with poll taxes, literacy tests and all manner of laws to disenfranchise Black Americans.

Along with legislation came enforcement through violence. Not only were Black people lynched and murdered throughout the post-Reconstruction South, but as Hannah-Jones notes, democratically elected governments were overthrown. In 1898 in Wilmington, North Carolina, a white supremacist mob attacked and burned Black neighborhoods and forced the resignation of the city's biracial government. In His Name Is George Floyd, Samuels and Olorunnipa explain, "The uprising reportedly killed at least a dozen Blacks and terrorized thousands, with rioters demanding that the bodies of the slain be left in the street as a warning to others."

The ramifications of this violence and discrimination are still present today, from the higher rates of incarceration for Black Americans compared to whites, to the persistent wealth gap between Black and white families. It took essentially another hundred years after the Civil War for the country to make an attempt at redressing the racial discrimination that preceded the war and persisted in such entrenched ways once the conflict itself was over.

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to His Name Is George Floyd. It originally ran in June 2022 and has been updated for the

May 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to His Name Is George Floyd. It originally ran in June 2022 and has been updated for the

May 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.