Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Sarah Hannah follows her critically acclaimed first volume of poetry, Longing Distance, with Inflorescence, a compelling memoir-in-verse for her mother, Boston Expressionist painter Renee Rothbein, and their intense relationship in which they struggle with Rothbein’s mental illness and eventual death from cancer. Hannah’s characteristic love of traditional poetic forms, wit, and fascination with the natural world continue to manifest in this sometimes shocking story that cannot fail to move scores of readers, including anyone who has cared for the sick, dealt with mental illness, or lost someone close to them. However, Inflorescence is far more than a narrative of sickness and loss. Through rich language and use of metaphor, most often that of wildflowers, their common names and lore, Inflorescence often treats its subject matter obliquely, making the personal and particular universal. In all, Hannah’s second volume of poetry examines unflinchingly the deep and difficult love between a mother and daughter, stares death in the face, and transforms a unique story into a series of luminous, transcendent truths.

[A] series of poems about grief, mother-daughter relationships, and the natural world that are as beautiful and varied as the botanical process that gives the collection its name. There is only one downside to Inflorescence: it is the final book written by Hannah, who committed suicide in 2007, shortly before its publication. It would be a shame if the manner of her death overshadowed the splendor of these poems; Hannah's command of form, her fluid yet controlled use of floral imagery, and her wicked sense of humor make these poems buzz with an energy that seems at odds with her early death.

Still, as Hannah writes in "An Elegy for Bells," "There are two sides to everything:/The ring and its ghost, the one/calling and the one called." In "Azrael (Angel of Death)," she conjures the subject in his many guises (lawyer, social worker, hospice nurse), but when she describes him as the lover her mother has "whored…married and divorced," the poem takes on a chillingly prescient tone: while Renee Rothbein may have died of a brain tumor, she was no stranger to suicide attempts. Indeed, Hannah writes that her mother had "always wanted/a brain tumor, some definitive (read: physical)/Disease people will breathe above a whisper". And in "Threepence, Great Britain, 1943," she creates a biography of her mother in immaculately composed tercets, revealing how Renee's "mum went funny,/Locked up and electroshocked, clamped down/On a bit to save her tongue."

Mental illness isn't the only ghostly presence in the collection, either. Section II, "In the Old House," addresses the abode pictured on the book cover, an ivy-covered cottage with three leaded windows facing out. It is a storybook house, and as in most fairy tales, it possesses a dark side. In one poem, "[t]he house does not forgive you," while in another "There is a backward world/Figured in the coldest state/of staring through the pane". "Progressive Dreaming" finds the speaker entering "the old house like a skilled burglar" and flitting through it, wraith-like, to find a dress that belonged to the woman who lived there before; the speaker knows that although the dress will fit, "it cannot be removed." Ultimately both the speaker and her mother haunt the house where they once dwelled, just as the "land plowed by tractors/Is haunted by oaks, by the circling/Protests of sparrows unnested." The urgency with which Hannah enjoins us to consider the prior history of both animate and inanimate objects (houses, trees) forces us to view the world through new eyes, to see everything around us as constantly blooming and decaying.

Hannah's wry wit, however, ensures that the poems never wallow in the despair that her subjects might suggest. "Common Creeping Thyme" places the speaker and her mother in a hospital room where they "wait and curse/While aides placate [them] with stale crackers/and CranGrape juice." She describes Westwood Lodge, a New England mental institution where her mother periodically stayed, as a "perennial/Resort…/Where Sexton strolled through noon, made moccasins,/And danced in a circle". Later in the same poem, the college-age speaker notes that "God's a white grub./He ate the lawn, but we can't afford to exterminate him". In a macabre play on "The 12 Days of Christmas," she even depicts her mother's death rattles as "two woodpeckers out of synch;/Three geese choking on crabgrass," and employs the formality of end-rhymed couplets in "Blessed Thistle" to play with Shakespearean language in a contemporary context. "The Missing Ingredient" provides the coup de grace, its accomplished use of acrostics transcending the merely clever to make a statement about a crucial aspect of depression. Hannah ends the collection with what she calls "Cantankerous Author's Notes," and these droll comments on literary allusions and references further underline that we have lost not only an extraordinary poet but also a simultaneously self-deprecating and well-read woman.

Abbreviated from "Biography-in-verse" by Marnie Colton

If you liked Inflorescence, try these:

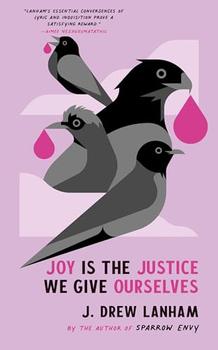

Joy Is the Justice We Give Ourselves

by J Drew Lanham

Published 2024

From J. Drew Lanham, MacArthur "Genius" Grant recipient and author of Sparrow Envy: A Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts, comes a sensuous new collection in his signature mix of poetry and prose.

by Kay Ryan

Published 2011

A major event in American poetry: The poet’s own selection of more than two hundred poems, offering both longtime followers and new readers a stunning retrospective of her earlier work as well as a generous selection of powerful new poems.