by Judy I. Lin

Xue, a talented young musician, has no past and probably no future. Orphaned at a young age, her kindly poet uncle took her in and arranged for an apprenticeship at one of the most esteemed entertainment houses in the kingdom. She doesn't remember much from before entering the House of Flowing Water, and when her uncle is suddenly killed in a bandit attack, she is devastated to lose her last connection to a life outside of her indenture contract.

With no family and no patron, Xue is facing the possibility of a lifetime of servitude playing the qin for nobles that praise her talent with one breath and sneer at her lowly social status with the next. Then one night she is unexpectedly called to the garden to put on a private performance for the enigmatic Duke Meng. For a young man of nobility, he is strangely kind and awkward, and surprises Xue further with an irresistible offer: serve as a musician in residence at his manor for one year, and he'll set her free of her indenture.

But the Duke's motives become increasingly more suspect when he and Xue barely survive an attack by a nightmarish monster, and when he whisks her away to his estate, she discovers he's not just some country noble: He's the Duke of Dreams, one of the divine rulers of the Celestial Realm. There she learns the Six Realms are on the brink of disaster, and incursions by demonic beasts are growing more frequent.

The Duke needs Xue's help to unlock memories from her past that could hold the answers to how to stop the impending war… but first Xue will need to survive being the target of every monster and deity in the Six Realms.

Xue'er has no place in the kingdom of Qi or any of the Six Realms. Her name means "Solitary Snow" and it surely fits a girl doomed to life as an "undesirable." Orphaned when she was young, all Xue has ever wanted is to stay with her beloved uncle, the poet Gao, who has cared for her ever since. But when she is twelve years old, Gao brings her to the House of Flowing Water and leaves her to be apprenticed as a qin player. She has a rare talent for the beautiful stringed instrument that earns her a contract with the prestigious entertainment house. Eventually her contract is purchased by the mysterious scholar Duke Meng and she leaves all that is familiar for the strange Manor of Tranquil Dreams. Every day seems to bring a new mystery. Why does her music seem to resonate here in a way it never has before? Why should a place that seems so otherworldly feel so much like home and a man who keeps so many secrets feel like the one her heart has always longed for? It soon becomes clear that Duke Meng is a ruler of the Celestial Realm, a place she has only ever known in poems and songs and childhood ghost stories. Here, monsters and gods battle for the soul of the universe, and Xue and her music may hold the only way to bring an end to the war. But with war comes sacrifice, and Xue must decide what she is willing to lose to save the world.

Judy I. Lin borrows deftly from many sources for this dazzling fairy tale and does so to wonderful effect, creating a tragic, romantic fable that unfurls gently, like a tapestry. The book itself is written in "verses" rather than "chapters" and the beautiful, melancholy poetry and songs referenced throughout come from ancient China. Much of her vast, highly detailed Six Realms (the heavenly and earthly planes that balance together to make the world) and the men, women, and deities who live in them are built from Chinese folk tales and mythology. And like those stories and ballads, the ending of this novel may not be entirely happy.

The heart of Lin's story, a young outcast slowly falling in love on the estate of her mysterious stern employer, is a wonderful homage to Daphne du Maurier and the Brontë sisters. But the sorrowful, determined Xue is a breed apart from Rebecca's wilting flower narrator and even a step beyond plucky Jane Eyre. Xue's brilliant resilience shines. There is steel in this heroine's spine. She never backs away from a confrontation, even with a goddess who could smite her with a thought while staring her down. She fights for love, for what is right, but above all for herself. The right to choose what your destiny will be, to refuse to accept who the world tells you that you must be, is the theme that defines Song of the Six Realms and the thing that comes to define Xue.

This is a novel to get lost in, to drift in like a gentle ocean, equal parts decadence and simplicity, true storytelling in its purest form. The world is vast and vivid, full of wild creatures and wilder magic. But there is an austerity and ancient feeling to it, as though we are reading a story that has been told many times. Lin wants her readers to spend just as much time visualizing and contemplating the delicate, delicious food her characters eat, the gardens they visit and the music they enjoy as she wants us to spend on the story itself. This is a book to be savored like rich wine or an old, romantic ballad. I found myself, more than once, picking it up to find a certain meal or poem just to let it wash over me again.

Song of the Six Realms will delight any teen who likes a touch of misty-eyed sorrow with their happily ever after. It is also a perfect fit for lovers of old myths where trickster gods and vengeful curses abound and the fate of the world hangs on the choices of one pure-hearted young woman.

Book reviewed by Sara Fiore

Music and poetry are a central part of Song of the Six Realms by Judy I. Lin. They are cornerstones of life in the kingdom of Qi and the Celestial world beyond it. Music may entertain but it also expresses feelings Lin's characters can't express with words. Xue'er cannot bring herself to confess she is falling in love with Duke Meng, so she tells him through an ancient song about a courtesan waiting for a lost love. In Lin's world, music is also a tool of magic. Xue'er's mastery of the qin turns out to be the key to unlocking the mystery the duke is trying to solve and the music they make together will mean either the saving or destruction of both their realms.

Music and poetry are a central part of Song of the Six Realms by Judy I. Lin. They are cornerstones of life in the kingdom of Qi and the Celestial world beyond it. Music may entertain but it also expresses feelings Lin's characters can't express with words. Xue'er cannot bring herself to confess she is falling in love with Duke Meng, so she tells him through an ancient song about a courtesan waiting for a lost love. In Lin's world, music is also a tool of magic. Xue'er's mastery of the qin turns out to be the key to unlocking the mystery the duke is trying to solve and the music they make together will mean either the saving or destruction of both their realms.

The guqin, or qin, as it is informally called, is a very real instrument whose existence dates back between three and five thousand years ago. Considered a type of zither, it is China's quintessential classical musical instrument. Its curved top is meant to represent heaven, and the wider base to represent the earth. It is played with one hand holding down the strings at intervals and the other plucking the notes. It was once the favored instrument of Chinese nobility and widely considered one of the four arts a nobleman was expected to master, the others being painting, calligraphy, and an ancient form of chess. Twenty years of study were required to be considered a proficient player. The qin is frequently seen in classic Chinese paintings and referenced in stories and poetry. The philosopher Confucius (551-479 BCE) was a qin player and composer. By the end of the Zhou Dynasty (1045-256 BCE), the instrument had gained popularity at court events and was often played at religious ceremonies.

But by the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE), the qin had begun to be seen as a means of more personal expression. Today, it is often considered a subtle and solitary instrument, meant for meditation and contemplation. Many of the songs composed for it date back thousands of years and the original composers' names are lost to history. The songs are meant to convey the deep and personal emotions of the player, as in the well-known piece "Lofty Mountain Flowing Water," a song Lin references in her novel. Qin songs often feature tales of doomed love or tragic sacrifice, such as the tragedy of Consort Yu. This is a popular Chinese story based in truth about a beautiful imperial consort to a king who sacrifices herself on the eve of a hopeless battle rather than be captured or killed by the enemy. For Xue, the song represents what she believes to be the hopelessness of her love for Duke Meng as well as her willingness to sacrifice whatever (or whoever) she has to in order to secure the safety of their worlds.

According to UNESCO, there are fewer than a thousand "well-trained" players of the qin today. Of the thousands of songs once written for it, only a few hundred remain frequently played, and many songs are now lost or drastically changed from their original forms.

This sad history of a beautiful instrument seems oddly fitting for a tragic fairy tale about a solitary young maiden who falls in love with the Duke of Dreams but must risk sacrificing her love to save the world.

Musician playing Guqin (late 18th century), courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Erik Larson

On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln became the fluky victor in a tight race for president. The country was bitterly at odds; Southern extremists were moving ever closer to destroying the Union, with one state after another seceding and Lincoln powerless to stop them. Slavery fueled the conflict, but somehow the passions of North and South came to focus on a lonely federal fortress in Charleston Harbor: Fort Sumter.

Master storyteller Erik Larson offers a gripping account of the chaotic months between Lincoln's election and the Confederacy's shelling of Sumter—a period marked by tragic errors and miscommunications, enflamed egos and craven ambitions, personal tragedies and betrayals. Lincoln himself wrote that the trials of these five months were "so great that, could I have anticipated them, I would not have believed it possible to survive them."

At the heart of this suspense-filled narrative are Major Robert Anderson, Sumter's commander and a former slave owner sympathetic to the South but loyal to the Union; Edmund Ruffin, a vain and bloodthirsty radical who stirs secessionist ardor at every opportunity; and Mary Boykin Chesnut, wife of a prominent planter, conflicted over both marriage and slavery and seeing parallels between them. In the middle of it all is the overwhelmed Lincoln, battling with his duplicitous secretary of state, William Seward, as he tries desperately to avert a war that he fears is inevitable—one that will eventually kill 750,000 Americans.

Drawing on diaries, secret communiques, slave ledgers, and plantation records, Larson gives us a political horror story that captures the forces that led America to the brink—a dark reminder that we often don't see a cataclysm coming until it's too late.

In the aftermath of the 1860 presidential election, the divided United States began to collapse as South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed by another six Southern states. Among the countless contentious points between the Union and the fledgling Confederacy was the existence of a 75-man Federal garrison in Charleston Harbor that would become the flashpoint for civil war. In The Demon of Unrest, Erik Larson weaves a gripping tale of America's slow-motion lurch toward war, placing the reader inside events as they unfold.

In seeking to answer what "malignant magic" could lead Americans to consider the unthinkable—a bloody civil war—Larson prefaces his narrative with the parallels between the "national dread" felt during the run-up to the certification of the Electoral College and the presidential inauguration in 1861 with that during the Capitol assault of January 6, 2021 (as electoral votes were counted). Dread is the watchword, and readers will experience it anew in Larson's taut telling.

In seven dramatic parts, The Demon of Unrest unfurls those eventful months in 1861, centering the stories of memorable individuals such as Major Robert Anderson, Union commander of Fort Sumter; Edmund Ruffin, fire-eating evangelist for Southern secession who fired the first shot at Fort Sumter; Mary Chesnut, the acclaimed Southern diarist and wife of a prominent planter and politician; and, of course, an embattled Lincoln ringed round by presumptuous allies and politicians who believed they knew better how to handle the crisis.

Traveling from Washington, D.C., where lame duck president James Buchanan's inaction bordered on treason, to the heady excitement of the newly formed Confederate government in its first capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Larson sharply dissects the Union's fresh cadaver in the months prior to the Sumter attack and posits that a wounded sense of honor warped Southern political sensibilities and befuddled Northern peacemakers eager to bring the secessionists back into the fold. Lincoln's stubborn belief, based "on basically no evidence," that a vast swathe of pro-Union sentiment still existed in the South after the defection of seven states reveals a startling naivete, Larson observes, and may account for the exceeding caution with which the new administration considered whether to resupply and reinforce Fort Sumter.

Larson's most incisive analysis scrutinizes the Southern planter aristocracy that called themselves "the chivalry." Here, Larson reveals a society bred and fed upon the tales of Sir Walter Scott, enamored of military titles and uniforms. Their simulacrum of nobility, Larson writes, was "affirmed on a daily basis by the fact of their possession of, and dominion over, a subservient population of enslaved Blacks." Valuing honor above all human traits, the chivalry "would happily kill to sustain it." It was a code duello mentality, and it symbolized a South stuck in time. Larson's most powerful analogy is that of South Carolina as Miss Havisham from Charles Dickens's Great Expectations: left at the altar of the Railroad Age, she stops her clocks and leaves the world behind, retreating into her "own world of indolence and myth."

Excavating a wealth of official documents and secret communiques, Larson crafts a thrilling tale with tick-tocking suspense around the book's prime target: Fort Sumter. Indeed, the true hero in Larson's telling is Anderson, a U.S. officer sympathetic to the South who nevertheless did everything in his purview (and beyond) to maintain his position and protect his soldiers from imminent attack. It was Anderson's secret decision—made without consulting the then-Secretary of War John B. Floyd, soon to defect to the Confederacy—to move his command, under the cover of Christmas night, from Fort Moultrie on the coast to the more defensible Fort Sumter in the middle of the harbor (see Beyond the Book). His cunning and situational awareness is even more impressive in the wake of long silences and confusing directions from Washington; Larson clearly admires him, as will the reader. Anderson's steadfast defense of Sumter, which became "a cauldron of heat, smoke, and lacerating shrapnel" for two April days under intense Confederate artillery fire, would cement his celebrity in the North after the stockade surrendered on April 13 and sailed for home on April 14.

Interspersed with the politics and intrigues are a raft of other appealing and appalling characters who orbited the Sumter drama, with James Henry Hammond a prime example of the latter. An ex-governor of South Carolina and senator who gave the historic 1858 Senate address that "Cotton is King," Hammond was a member of the chivalry, a pro-slavery advocate who "worked his slaves hard" and barely recovered politically from a sexual scandal including four of his nieces. More palatable is the bemused and observant Sir William Howard Russell, The Times of London's special correspondent, who wrote about his meetings with prominent people North and South. Larson outlines Russell's keen conviction that "Northerners had little understanding of their brethren below the Mason-Dixon Line" and that Southerners viewed their Northern counterparts as cowards. Russell's writings captured both sides' central misunderstanding of "the other," which led to missteps and miscommunications between Lincoln's administration and the Confederacy during these key months.

Adding an indelible sparkle to the narrative are Larson's plumb pickings from Mary Chesnut's diary. A reliable source of comedic relief, Chesnut chronicles the mood and spirit of the Confederacy as she goes "social spelunking" in Montgomery and Charleston. Included is Chesnut's lighthearted "flirtation" with South Carolina's handsome ex-governor and bon vivant John L. Manning, a source of friction with Mary's husband, James: "After dinner, Mr. Chesnut made himself eminently absurd by accusing me of flirting with John Manning, &c. I could only laugh—too funny!" Known mostly from her folksy inclusion in Ken Burns's iconic documentary The Civil War, she is discussed in all her contradictions by Larson. "Mary had a clear-eyed view of slavery," Larson writes, accepting it as a foundation of Southern society even as she was honest about and spoke against the sexual abuse of enslaved girls and women at the hands of white slaveowners. She is an enigma of sorts, but a categorical delight to discover through the pages of her diary.

Covering the dicey days leading up to war, The Demon of Unrest is cinematic in scope, intimate in detail and charmingly written. Even more importantly, the parallels of 1861 with the electoral riots of 2021 make this book an urgent call to learn from history's mistakes. This is narrative history at its best: instructive, timely and utterly enthralling.

Book reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski

As Erik Larson recounts in The Demon of Unrest, the first shots of the American Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter, off the coast of South Carolina, at 4:30 a.m. on April 12th, 1861. Thirty-six hours later, Union Major Robert Anderson and his small force surrendered with no loss of life. Ironically, the only casualties sustained came during the fort's 100-gun salute when an artillery round exploded prematurely, killing Pvt. Daniel Hough and mortally wounding another. The Union would reclaim the fort four years later and Anderson would be the one to raise the same American flag the Confederates fired upon.

As Erik Larson recounts in The Demon of Unrest, the first shots of the American Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter, off the coast of South Carolina, at 4:30 a.m. on April 12th, 1861. Thirty-six hours later, Union Major Robert Anderson and his small force surrendered with no loss of life. Ironically, the only casualties sustained came during the fort's 100-gun salute when an artillery round exploded prematurely, killing Pvt. Daniel Hough and mortally wounding another. The Union would reclaim the fort four years later and Anderson would be the one to raise the same American flag the Confederates fired upon.

Today, Fort Sumter is one part of the Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historic Park, overseen by the U.S. National Park Service. First added to the National Park Service as a national monument in 1948, it was redesignated in 2019 under its current pairing with Fort Moultrie. Unlike Fort Moultrie, which is located on Sullivan's Island, Fort Sumter is only accessible via boat. According to the Charleston tourism bureau, more than 800,000 people visit Fort Sumter every year.

The only commercial boat transportation to Fort Sumter is via Fort Sumter Tours, an authorized NPS concessioner. Private boats are not allowed at the fort. The ferry takes about thirty minutes to reach the fort, but visitors are allowed a full hour to roam and listen to NPS ranger talks about the fort's history and significance. The ferry ride also provides visitors with beautiful views of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown and the Ravenel Bridge, according to an article by Sharon Williams for State by State Travel. A museum inside the fort relates the history of Sumter, and visitors can view the same flag that was flying when it was first attacked. Rangers are on hand to answer questions as visitors are encouraged to explore the fort on their own.

For those unable to visit in person, the American Battlefield Trust provides an online and immersive 360-degree virtual tour of Charleston and Fort Sumter (compatible with a VR headset, no less!). Video tours and a helpful animated battle map are important offerings for those who are unable to travel but still desire to see Fort Sumter and understand its geographical and historic importance.

Forts Sumter and Moultrie recently commemorated the first shots of the Civil War on April 13–14, 2024, marking the 163rd anniversary of the beginning of the war. According to an NPS press release, "living historians in period clothing" portrayed soldiers and civilians at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie "to help provide insight into the tension filled days that preceded the war." From an embattled American Civil War sea fort to a popular and beautiful tourist attraction, Fort Sumter continues to draw thousands of visitors every year to reflect on a turbulent time in the nation's history.

Aerial view of Fort Sumter in 2017, courtesy of Library of Congress

by Eve J. Chung

Daughters are the Ang family's curse.

In 1948, civil war ravages the Chinese countryside, but in rural Shandong, the wealthy, landowning Angs are more concerned with their lack of an heir. Hai is the eldest of four girls and spends her days looking after her sisters. Headstrong Di, who is just a year younger, learns to hide in plain sight, and their mother—abused by the family for failing to birth a boy—finds her own small acts of rebellion in the kitchen. As the Communist army closes in on their town, the rest of the prosperous household flees, leaving behind the girls and their mother because they view them as useless mouths to feed.

Without an Ang male to punish, the land-seizing cadres choose Hai, as the eldest child, to stand trial for her family's crimes. She barely survives their brutality. Realizing the worst is yet to come, the women plan their escape. Starving and penniless but resourceful, they forge travel permits and embark on a thousand-mile journey to confront the family that abandoned them.

From the countryside to the bustling city of Qingdao, and onward to British Hong Kong and eventually Taiwan, they witness the changing tide of a nation and the plight of multitudes caught in the wake of revolution. But with the loss of their home and the life they've known also comes new freedom—to take hold of their fate, to shake free of the bonds of their gender, and to claim their own story.

Told in assured, evocative prose, with impeccably drawn characters, Daughters of Shandong is a hopeful, powerful story about the resilience of women in war; the enduring love between mothers, daughters, and sisters; and the sacrifices made to lift up future generations.

Daughters of Shandong is the debut novel of Eve J. Chung, a human rights lawyer living in New York. Overall, First Impressions readers loved the book, awarding it an outstanding average rating of 4.8 out of 5 stars.

What Daughters of Shandong is about:

This book is a work of fiction, but it's based on the real life of the author's grandmother. A mother and three daughters are left behind when the more powerful members of their Nationalist family flee to escape Communists during the revolution. The story is told from the perspective of the oldest daughter, Li Hai, and the author does an astonishing job of capturing the thoughts of an adolescent girl dealing with both inconceivable trauma and everyday concerns (Kathleen L). This is also a character study of the women, both young and old, their strengths, the cultural rules accepted by the mother, and the awareness of the daughters that these rules are not fair (Susan W).

Readers were immediately swept up in the story's fast pace and absorbing details.

This novel was one which I could not stop thinking about. When I wasn't reading it, I couldn't wait to return to the story. There were some difficult scenes throughout but reading about Hai and the treacherous journey from Shandong to Taiwan was ultimately gratifying and I rooted for these women through every step. I cannot recommend this novel enough! (Darlene B). A fast-paced historical fiction novel that keeps the reader turning pages until the end (Cindy B).

Many felt that the book was thoroughly enjoyable despite its difficult subject matter.

If a book taking place during a war can be called enjoyable, this is it. I say enjoyable based on the mother/daughter relationships, the three-dimensional characters and the rising above the circumstances, which almost makes the reader forget the horrors in favor of the power of the storyline (Marie M). Chung's writing is descriptive without being overly expansive. Daughters of Shandong was a real pleasure to read and I hope Chung continues to write (Laurie B).

Reviewers also thought that the novel's exploration of the treatment of girls and women was substantial and important.

As a Chinese daughter myself, I resonated deeply with Hai and many of the struggles she went through in trying to reconcile her identity with her culture…More than any other novel I've read in recent years (specifically ones written in contemporary times), this one does a great job exploring the internal battle that many of the women who grow up in restrictive cultures face (Lee L). From the story's emphasis on gender inequality, I learned about the damage that it has done to individuals and its harsh effects on society. I was moved by the relationships and the portrayal of the mother and her daughters in their relentless struggle to survive as their lives were continually torn apart (Patricia W).

In general, readers found Daughters of Shandong to be a fascinating and stunning work of historical fiction.

Daughters of Shandong is now on the top of my list of historical fiction novels. The author transports the reader into the eye of Chinese history and shows the incredible strength and fortitude of women who refused to be oppressed so that their daughters could rise above the hardships of cultural and political challenges and injustice (Melissa C). So many great details about the times and places, I could not put this book down! I look forward to reading other books by Eve J. Chung and want to share this story with my teenage granddaughter (Ruth H). Amidst the backdrop of resistance and resilience, Chung weaves a tale of hope and love that empowers this family to conquer insurmountable odds. Her storytelling skillfully explores the bonds of family and the strength that emerges from adversity, delivering a narrative that is both heart-rending and hopeful (Lani S).

Book reviewed by BookBrowse First Impression Reviewers

Eve J. Chung's debut novel Daughters of Shandong focuses on the mother and daughters of a landowning family who flee China for Taiwan as a result of the Communist revolution in the late 1940s. Chung has spoken about how she was motivated to write the book by her maternal grandmother's experiences of that period of history.

Eve J. Chung's debut novel Daughters of Shandong focuses on the mother and daughters of a landowning family who flee China for Taiwan as a result of the Communist revolution in the late 1940s. Chung has spoken about how she was motivated to write the book by her maternal grandmother's experiences of that period of history.

However, what became a work of fiction started as a simple attempt to record her family's past. In a note to readers, Chung portrays the special relationship she formed with her grandmother from having lived with her in Taiwan as a child. While they were close, bonding over competitive billiards and period dramas, Chung knew little of her grandmother's history as a refugee. After her grandmother passed away in 2013, Chung decided to record details about her life with the help of her mother and other relatives, for the purpose of sharing them with her children. But realizing that there were simply too many unknowns, she ended up embarking on the much larger project of fictionalizing her grandmother's story.

In an interview with Sampan, Chung talks about how another thread that informed her writing of Daughters of Shandong was her work as a human rights lawyer, which has focused on gender equality. Writing about a fictional Chinese family in the 1940s and '50s gave her the opportunity to address the sexism and misogyny inherent in society at that time. The poor treatment of women and girls, who are often shown to be given less importance and value than their male counterparts, is a major theme of the novel.

"I hope it helps draw attention to the entrenched sexism that women face in many cultures around the world," she says. Mentioning that she has seen both changes and continued "challenges" in her generation regarding sexism in Chinese culture, Chung also stresses that her interest in gender equality is not specific to any one group of people but extends across time and place, and also alludes to the unique difficulties and issues that women refugees face: "All over the world, there is backlash against women's rights, which is chipping away at hard-earned progress for gender equality—this is true as well in the country that I live in, the United States...What saddens me most is that there are still many women and girls who are refugees and/or suffer as a result of armed conflict, just like my grandmother and her family."

In a recent article for Writer's Digest, Chung writes about choosing the cover art for her novel, which ended up being a painting by Wang Yidong, an artist from her grandmother's home province of Shandong. In conjunction with this, she comments on the inspiration behind the novel's title, explaining that while her grandmother's remains are buried in Taipei, her roots were an important part of her identity: "Among Chinese people, it is common to ask a person where their lao jia, their 'old home' is—the roots of their origin, which is not where they were born, but where their family is from."

by Xochitl Gonzalez

1985. Anita de Monte, a rising star in the art world, is found dead in New York City; her tragic death is the talk of the town. Until it isn't. By 1998 Anita's name has been all but forgotten—certainly by the time Raquel, a third-year art history student is preparing her final thesis. On College Hill, surrounded by privileged students whose futures are already paved out for them, Raquel feels like an outsider. Students of color, like her, are the minority there, and the pressure to work twice as hard for the same opportunities is no secret.

But when Raquel becomes romantically involved with a well-connected older art student, she finds herself unexpectedly rising up the social ranks. As she attempts to straddle both worlds, she stumbles upon Anita's story, raising questions about the dynamics of her own relationship, which eerily mirrors that of the forgotten artist.

Moving back and forth through time and told from the perspectives of both women, Anita de Monte Laughs Last is a propulsive, witty examination of power, love, and art, daring to ask who gets to be remembered and who is left behind in the rarefied world of the elite.

Brooklyn-based novelist Xochitl Gonzalez is an inspiring writer to follow. At forty, she decided to pivot in her career and pursue a lifelong dream of writing fiction. She enrolled in the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop and in 2021 received an MFA. A year later, her debut novel Olga Dies Dreaming was published and quickly hit the NYT bestseller list. In that remarkable novel, Gonzalez managed to combine an approachable, entertaining family story with powerful considerations of identity, poverty, race, capitalism, corruption, love, honor, elite privilege, feminism, Puerto Rico and its history and politics.

Now, in her second novel, Anita de Monte Laughs Last, readers are in for another thrilling ride. Again, Gonzalez delivers a satisfying, propulsive story as she relates the sometimes-parallel experiences faced by two Latina women who, a decade apart, must each navigate elitist, alien environments. As her characters confront the mores and expectations of the New York art world and Ivy League academia, Gonzalez points a high beam into the shadows to locate the traps of racism, sexism and class biases that undercut her main characters at every turn. In so doing, she once again deftly incorporates into her fiction the piercing social critique that readers have come to admire.

The book opens in the mid-1980s. Up-and-coming Cuban American artist Anita de Monte is attending a crowded art-world party. De Monte feels elated, hardly even bothered that her faithless, superstar husband, sculptor Jack Martin, is off flirting with a young acolyte. Dancing the night away in a silver sequined dress, Anita nurses the thrilling knowledge that she has finally landed a solo exhibition in Rome at a prestigious gallery. But in only a few hours, Anita de Monte will be killed—hurtled out of an apartment window during a venomous argument with Jack.

Flash forward a decade. Raquel Toro is one of two non-white undergraduates in Brown University's art history department, and although she knows she is smart and ambitious, she still grapples with the sense of being on a completely different frequency from most of her cohort and professors. As she enters her senior year, Raquel must choose her graduation thesis topic, a choice complicated by others hoping to influence her path. Must she follow the advice of her paternalistic advisor and write her thesis on the sculptor Jack Martin? When Raquel learns the full story about the life of vanished artist Anita de Monte, she faces the uncomfortable realization that the women artists who speak to her experience rarely make it on to university art history syllabi. Things grow more complicated yet when handsome artist Nick Fitzsimmons turns his attention to her; how much of herself will Raquel need to cede in order to meet his possessive and needy demands in their relationship?

The character of Anita de Monte—whose biography and artwork are closely based on the artist (note the near anagram) Ana Mendieta (see Beyond the Book)—displays a high-octane, intense personality, and the chapters focused on her story really shine. Things begin to get a little supernatural midway through—perhaps not surprising when one of a novel's first-person narrators is no longer living—and here I did wonder where the author was heading. The author kept a firm hand on the tiller, however, creating in Anita a character so clearly drawn that it somehow felt plausible that her voice might reach beyond the grave. So, my advice is simple: buckle up and prepare for a bit of fictional turbulence. Gonzalez has fashioned a memorable character in Anita, a thrilling presence who nonetheless stays within the novel's sometimes wacky boundaries.

Gonzalez utilizes a first-person point of view as Anita and Raquel alternate telling their stories. Although Raquel's chapters fall more squarely within a classic narrative arc, and her milder voice cannot match Anita's powerful personality and spirit, her steps towards developing her own agency and confidence in the face of microaggressions and manipulations ground the novel, and will be particularly compelling to many readers.

In the end, Gonzalez's arrows all hit their targets—the elite worlds of academia and the fine arts, racism, misogyny, gaslighting, power dynamics—with a full, furious force. That said, the book is not without its flaws. Powerful convictions can at times turn the baddies into straw men. Several chapters written from Anita's husband's egocentric perspective fell flat for me, although they successfully advance the plot. A pivotal scene involving Raquel's cruel hazing from jealous fellow female art students also felt a bit improbable, yet is perhaps only one short step away from the less clearly expressed bullying that happens in life all the time.

Overall, this is a rollicking and insightful read, and I heartily recommend it.

Book reviewed by Danielle McClellan

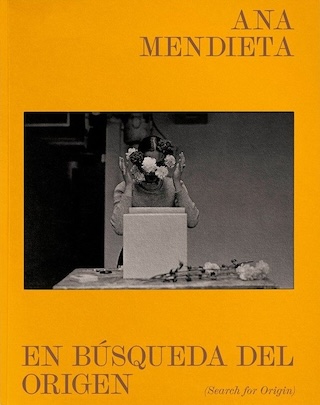

The title character in Xochitl Gonzalez's Anita de Monte Laughs Last is closely based on the artist Ana Mendieta. Although Mendieta's shocking death at the age of thirty-five has overshadowed her artistic legacy in the public imagination, Mendieta was a rising star at the time of her death, and her creative work continues to hold relevance today.

The title character in Xochitl Gonzalez's Anita de Monte Laughs Last is closely based on the artist Ana Mendieta. Although Mendieta's shocking death at the age of thirty-five has overshadowed her artistic legacy in the public imagination, Mendieta was a rising star at the time of her death, and her creative work continues to hold relevance today.

Born in Cuba in 1940, Ana Mendieta was the second of Ignacio and Raquel Mendieta's three children. In 1952, Ana, age 12, and her sister Raquelin, 14, were sent to America as part of a program known as the Peter Pan Project. In the years immediately following the Cuban Revolution, Cuban children were sent alone to America by parents panicked over erroneous reports that the new Castro government was planning to "terminate parental rights, assume custody of all Cuban children, prohibit religion and indoctrinate them into communism." Though those threats never came to fruition, between 1960 and 1962, over 14,000 unaccompanied minors, ages 6–18, were put on airplanes and flown to Miami.

The sisters were initially sent together to an Iowa reform school, where beatings and confinement were common punishments, and then separated and sent to a series of foster homes. "Ana felt," according to journalist Shawn O'Hagan, "abandoned by her family and isolated from her homeland. She did not see her mother and brother again until 1966, or her father, who was jailed for disloyalty to Castro, until 1979. He died soon after arriving in America." The experience certainly shaped Mendieta and her later artistic work.

In college, Ana Mendieta studied painting at the University of Iowa. She became a student in the university's Intermedia Program, created by German artist Hans Breder. Inspired by European radical conceptual art, the program encouraged students to "throw off creative constraint" and explore a wide variety of artistic forms, including video and performance art. As a student, Mendieta was able to meet a number of contemporary avant-garde artists who visited the program. Breder and Mendieta also had a ten-year romantic relationship, and she was featured in his 1973 photo series "La Ventosa."

In the 1970s, Mendieta spent several summers in Mexico, which she described as "like going back to the source, being able to get some magic just by being there." She created a number of installations that incorporated parts of her body (or silhouettes or footprints) into a natural landscape. She also used elements such as stones, flowers, driftwood, bark and leaves in her work, using the term "earth body" to refer to her installations.

According to the curators of a 2024 Mendieta exhibit in León, Spain, "Ana Mendieta created a powerful body of work defined by the body and its encounter with nature." In her 15-year career, she "developed her own hybrid practice, which fused aspects of 'body art' and 'land art.'" Mendieta worked in multiple mediums including video, photographs, installations, drawings and paintings.

Mendieta moved to New York in 1978 and there became friends with some of the leading feminist artists of the day. She also met and fell in love with the sculpture Carl Andre. The two were in many ways opposite—he was methodical and liked routines, she was more spontaneous and intense. Their relationship became combative at times. The couple split, and Mendieta moved to Rome, a city that she loved. She told friends that it was "a cross between Cuba and New York" and that "she felt accepted there in a way she never was in America."

Mendieta and Andre reunited and held a small, private wedding in Rome in January of 1985. Then they returned to New York. Early in the morning of September 8, 1985, Ana Mendieta fell out of a 34th floor apartment. Many believed that Andre was guilty of pushing or throwing her out during a drunken argument; the police reported that Andre had scratches on his body, and neighbors reported hearing Ana's cries just before she fell. However, Andre was eventually acquitted of Mendieta's murder on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence.

Today, a growing number in the art community hope to move attention away from Ana Mendieta's death to her life, recognizing the important legacy she has left behind. The exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Castilla y León points this out: Through "relationship with the visible and the invisible, the permanent and the ephemeral," she found "her way of making the unspeakable explained through the trace of the body and its insertion into nature….Ana Mendieta never stopped reinventing herself."

Catalog from 2024 Ana Mendieta exhibition, courtesy of Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.