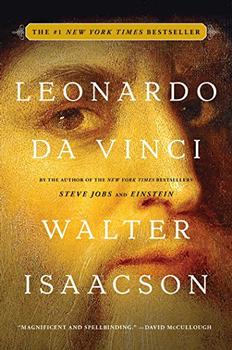

At BookBrowse, we believe that books are not an end in themselves but a jumping off point to new avenues of thought and discovery. This is why, every time we review one we also explore a related topic. Here is one such "beyond the book" article by Rose Rankin, originally titled "The Education Revolution" and written in conjunction with her review of Walter Isaacson's Leonardo da Vinci:

The term "Renaissance man" means a polymath, or someone who excels at many fields. Few people earned that moniker as brilliantly as Leonardo da Vinci, who actually lived during the height of the Italian Renaissance. Making his accomplishments even more remarkable is the fact that he didn't receive much in the way of a formal education. Leonardo was rightfully proud that he didn't "accept dusty Scholasticism or the medieval dogmas that had accumulated since the decline of classical science and original thinking," as Walter Isaacson explains in his biography of the Renaissance master.

The term "Renaissance man" means a polymath, or someone who excels at many fields. Few people earned that moniker as brilliantly as Leonardo da Vinci, who actually lived during the height of the Italian Renaissance. Making his accomplishments even more remarkable is the fact that he didn't receive much in the way of a formal education. Leonardo was rightfully proud that he didn't "accept dusty Scholasticism or the medieval dogmas that had accumulated since the decline of classical science and original thinking," as Walter Isaacson explains in his biography of the Renaissance master.

But while Leonardo himself was working and discovering, education in the Renaissance was undergoing important changes, ultimately setting the stage for the study of liberal arts that we still recognize today. The program of Scholasticism, a method of study that dominated the Middle Ages, was being swept aside as European societies re-discovered works by ancient Greeks and Romans. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in Italy, this evolved into the studia humanitatis, the educational program of the Renaissance.

The studia humanitatis consisted of grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy based on the reading of classical Greek and Latin authors. In the 1400s both the texts and the purpose of education changed. Writers whose works had been lost to Europeans for centuries were re-discovered, and education became a means to self-improvement. The development of humanism and its emphasis on mankind rather than theology prepared the ground for this shift in the larger purpose of education.

For example, in the first years of the fifteenth century the humanist scholar and teacher Pier Paolo Vergerio wrote a treatise on education, The Character and Studies Befitting a Free-Born Youth. In it he said, "Thus in philosophy we find rules explaining what one may profitably do or shun, but in history we find examples to follow." Humanists valued both philosophy and history because they focused on bettering the individual through knowledge of virtuous actions and examples of people in the past. This was a significant change from the Middle Ages, when past events were interpreted as the progression of God's will, not the actions of independent people.

The value placed on the history of non-Christian ancient people in the early Italian Renaissance removed the veneer of theology from history, and humanists began to see the subject as the choices and actions of men, not the will of God. This new outlook allowed humanists to see value in the personal qualities of historical characters, and they praised certain people for their valor and successes and condemned others for their failures or mistakes. Teachers used texts from ancient Romans including Livy and Valerius Maximus, and over the course of the fifteenth century, they added ancient Greeks like Herodotus and Thucydides. In the process they fostered the critical study of history, which was the beginning of the modern subject as it is studied today.

Likewise, moral philosophy was taught via these ancient authors and others including the poems of Virgil, Terence, Horace, and Ovid. As Paul F. Grendler explained in Schooling in Renaissance Italy, these morals were considered the basis of a loyal, industrious (male) citizen: "He learned to honor laws, institutions, and customs, as well as persons. Social ethics consisted mostly of loyalty to family, friends, and patria, especially patria [homeland]."

Underpinning all these changes was the revival of classical rhetoric—meaning the ability to give an eloquent speech and write persuasive letters and documents. The study of rhetoric in the Renaissance was based overwhelmingly on the writings of the ancient Roman politician Cicero. Whereas in the Middle Ages rhetoric meant formulaic letter writing with very specific salutations and structure, Renaissance rhetoric emphasized emulating the style of Cicero's letters and speeches, particularly their ability to persuade and teach.

Renaissance princes, politicians, and businessmen were expected to take part in the active civic life of their cities, kingdoms, and republics; therefore they needed to know how to communicate. Cicero provided extensive examples of emotional, moving letters and exhortations to duty and service. "The human situations and civic values that filled Cicero's letters clinched their primacy for the Renaissance," according to Grendler. "The letters taught not only practical rhetorical skills, but personal morality in a social context." As a result, Cicero's style became the centerpiece of an educational program that focused on improving the individual and helping them contribute to society.

Underpinning all these changes was the revival of classical rhetoric—meaning the ability to give an eloquent speech and write persuasive letters and documents. The study of rhetoric in the Renaissance was based overwhelmingly on the writings of the ancient Roman politician Cicero. Whereas in the Middle Ages rhetoric meant formulaic letter writing with very specific salutations and structure, Renaissance rhetoric emphasized emulating the style of Cicero's letters and speeches, particularly their ability to persuade and teach.

Renaissance princes, politicians, and businessmen were expected to take part in the active civic life of their cities, kingdoms, and republics; therefore they needed to know how to communicate. Cicero provided extensive examples of emotional, moving letters and exhortations to duty and service. "The human situations and civic values that filled Cicero's letters clinched their primacy for the Renaissance," according to Grendler. "The letters taught not only practical rhetorical skills, but personal morality in a social context." As a result, Cicero's style became the centerpiece of an educational program that focused on improving the individual and helping them contribute to society.

The changes to education that took place in the Renaissance—an appreciation of history, an emphasis on persuasive and stylistic communication, a reverence for classical literature and Latin—shaped education into the twentieth century. Today, the liberal arts education that focuses on research and writing is a direct outgrowth of the studia humanitatis, and only in very recent decades have the classical languages Latin and Greek taken a backseat. The educational program developed by humanists also became a way for middle-class students in the Renaissance to climb the social ladder with marketable skills—and education remains as much a vehicle for socioeconomic advancement today as it was 500 years ago.

Picture of bust of Cicero at Palazzo Nuovo - Musei Capitolini - Rome by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro