"Children have a right to books that reflect their own images and books that open less familiar worlds to them…for those children who had historically been ignored – or worse, ridiculed – in children's books, seeing themselves portrayed visually and textually as realistically human was essential to letting them know that they are valued in the social context in which they are growing up…At the same time, the children whose images were reflected in most American children's literature were being deprived of books as windows into the realities of the multicultural world in which they are living, and were in danger of developing a false sense of their own importance in the world."

- Rudine Sims Bishop, from, "Reflections on the development of African American Children's Literature," Journal of Children's Literature, Vol. 38, Iss. 2 (Fall 2012): 5-13.

When you look at the representation of book clubs in the media in general, they are often portrayed as social groups that drink wine and gossip and - if there's time - discuss rather unchallenging works of "women's fiction." This view is shared by many readers. In fact, when we asked people who read at least one book a month and who are not in a book club their reasons for not being in one, 33% said they thought book clubs are primarily social groups not engaged in serious book discussion!

While there is truth to the idea that many book clubs make time for social discussion and that some enjoy a glass of wine (more on these topics in future posts), data shows that book groups generally read high-quality, thought-provoking books that spur intellectual debate across a range of genres and topics.

You are probably familiar with the age old saying, "Rules were meant to be broken." And when it comes to grammar and the English language, people have been breaking rules long before Shakespeare wrote his first sonnet.

Part of this is because English has always been such a fluid language. Just flip through an English dictionary and you'll find words from all over the world: rendezvous from France, rickshaw from Japan, and even jazz from West Africa. And if you were to spend some time with a dictionary from a century ago, you'd find many words we use today but with substantially different meanings.

All of this happens because people break the rules. They start using new words, repurpose existing words, or find new shortcuts to say things the way they want. Maybe another word from another language describes something better than the current word for it in English, or maybe the traditional way of saying something is just too clunky or formal for the modern world. Languages change and evolve, and perhaps none more so than English itself.

But there's a danger to breaking the rules too much. Remember: language is about communication, and the tighter your grasp over the language, the more successfully you can communicate. It all comes down to one thing: You have to be aware of the rules before you can break them.

I'm excited to share with you my article on the American Library Association's Book Club Central website: "So Much Love for Library Book Groups!"

I'm excited to share with you my article on the American Library Association's Book Club Central website: "So Much Love for Library Book Groups!"

If you find it interesting, please do share with others!

It's based on our recently released report: The Inner Lives of Book Clubs: Who Joins Them and Why, What Makes Them Succeed, and How They Resolve Problems.

Here's a brief snippet from the article:

It's summer, a time when you might be looking for a captivating read to bring along on vacation. If your book club is seeking thrills, or looking to solve a mystery; look no further than these six books, all of which are recently released in paperback with solid reviews and helpful guides that should spark lively discussions in your group.

If you have a penchant for unreliable narrators, consider Alice Feeney's Sometimes I Lie or Greer Hendricks' The Wife Between Us, both of which delightfully upend expectations and keep the reader guessing to the end. Ali Land's Good Me, Bad Me and Christopher J. Yates' Grist Mill Road explore the psychological implications of witnessing or experiencing a terrible crime secondhand. Mariah Fredericks' A Death of No Importance is a historical mystery set in the early 20th century for fans of period pieces, and Jane Harper's Force of Nature features a sharp-minded federal agent tracking a killer in the Australian Outback (and made BookBrowse's 2018 Best Books list).

As reported in our recent publication The Inner Lives of Book Clubs, the vast majority of book club members surveyed describe their group as a vital and fun aspect of their life. They report enjoying a sense of community and a deepened sense of empathy and, often, close personal friendships.

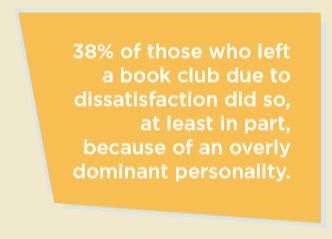

But even in the most harmonious of book clubs, conflict is likely to arise at some point, and if disagreements are not resolved, problems may grow more intense and people may end up leaving their book club - or worse - they may reach a breaking point and disband the group altogether.

In our research we've found that one common cause of conflict are overly dominant personalities (ODPs) - people who, whether intentionally or not, occupy too much of the limelight and overpower one or more elements of the book club, such as book selection or the discussion itself.

In our research we've found that one common cause of conflict are overly dominant personalities (ODPs) - people who, whether intentionally or not, occupy too much of the limelight and overpower one or more elements of the book club, such as book selection or the discussion itself.

We have one member who is subtly dominant and sabotages book choices that are more challenging.

One member does a lot of research into books but only in the genre she likes. Because she has done so much work we often feel obligated to choose her books.

One of the original founders sees it as her book club. She talks at least twice as much as anyone else and there can be no changes to our format without her blessing. Members have quit because of this.

One of the members would just talk on about herself and her family; the rest of us couldn't get a word in. It was supposed to be a fun night out but it wasn't, so I quit.