by Maureen Sun

After years of estrangement, Minah, Sarah, and Esther have been forced together again. Called to their father's deathbed, the sisters must confront a man little changed by the fact of his mortality. Vicious and pathetic in equal measure, Eugene Kim wants one thing: to see which of his children will abject themselves for his favor— and more importantly, his fortune. From their childhood in California to the depths of a mid-Atlantic winter, the solitary sisters Kim must face a brutal past colliding with their present. Grasping at their broken bonds of sisterhood, they will do what is necessary to escape the tragedy of their circumstances—whatever the cost.

For Minah, the eldest, the money would be recompense for their father's cruelty. A practicing lawyer with an icy pragmatism, she dreams of a family of her own and sets to work on securing her inheritance. For Sarah, a gifted and embittered academic who wields her intelligence like a weapon, confronting her father again forces her to reckon with the desperation of her present life. It is left to the youngest— directionless and loving Esther— to care for their father in her lonely quest to do right by everyone. A fortune pales in comparison to the prospect of finally reuniting with her sisters.

With a legacy of violence haunting their lives, the sisters dare to imagine a better future even as their father's poison courses through their blood. A contemporary reimagining of Dostoevsky's dark classic, The Brothers Karamazov, Maureen Sun's brilliant debut is a vivid and visceral exploration of rage, shame, and the betrayals of intimacy.

The Kim sisters—Minah, Sarah, and Esther—have just learned their father is dying of cancer. Minah, the eldest, is a high-functioning New York City lawyer determined to start a family. Sarah is a literature professor at Rutgers and has just become reacquainted with her elder sister after estranging herself from her family for over a decade. Esther, the youngest and in some ways most coddled, has been adrift after dropping out of college a few years prior. Their father, Eugene, has moved to New Jersey to live in an apartment complex he owns as part of a real estate portfolio that makes up a significant portion of his vast wealth. He arrives with expectations that his daughters care for him in his final days, and also with a bombshell: he has an "illegitimate" son named Edgar, who is a doctor living in New York. But this is not the sentimental tale of a family uniting to say goodbye to a beloved patriarch. Eugene, we learn from the beginning, terrorized his two eldest daughters during their youth with verbal and physical abuse (Esther was spared largely because she managed to ingratiate herself with the family next door and therefore was rarely at home).

Minah is determined to swallow her fury and make nice with her father because she wants to inherit his wealth (rumored to total in the millions), and she convinces Sarah, who despite being Eugene's "favorite" was the most frequently victimized, to do the same. Minah believes Edgar is likewise on the scene solely to get his name into Eugene's will. And if Eugene dies before writing a will at all, she knows that a court is likely to recognize Edgar as an equal beneficiary to Eugene's "legitimate" children. This, to Minah, would be an injustice, given that Edgar never suffered the abuse Eugene inflicted on his daughters.

In her debut novel, Maureen Sun deftly excavates the psychological fallout from parental abuse through the personalities, ambitions, and failures of the three sisters. Minah has latched on to the prospects of family, religion, and heritage making her whole. The only one of the sisters to have spent time in Korea, being Korean is important to her in a way that it isn't to the others, whose only reference point to their heritage is Eugene. Minah recalls initially feeling like her genetic connection to her father was a "disease," and being rejected by some of her peers in school because she was Asian. But after traveling to Korea, she had an awakening:

"It's amazing how much racism I'd internalized. So much self-loathing. That's why I went to Korea after high school, to stop hating myself and learn more about myself. I learned to speak Korean. I learned more about my family. But I still wanted more than anything not to be his child."

Sarah, the most tragic of the three, has never made it past that last sentiment, and in fact her hatred of Eugene consumes her life. Her career is in stasis because she lacks the ruthless ambition required for a life in academia. Her brilliant mind for literature withers teaching freshman composition classes and she avoids romance after her first serious boyfriend left her for another woman. A great part of the novel's suspense centers on Sarah's fragile psyche, as she seems to have been hanging by a thread even before Eugene reentered her life.

The Sisters K is a retelling of Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, so the sisters are refracted through a prism of the source material as well as through the abuse they suffered in childhood. Minah is an impulsive spendthrift who seems the most likely to outright murder Eugene, much like the eldest Karamazov, Dmitri. Sarah, like her counterpart Ivan, is a bookish intellectual searching for something meaningful to believe in. Esther is the moral compass of the family, like the deeply spiritual Alexei. Edgar is based on the illegitimate son of Fyodor Karamazov, Smerdyakov, but Sun makes the shrewd choice to develop him into a more sympathetic character than Dostoevsky's. Edgar is conniving, but he is after Eugene's wealth for the sake of his son more than for his own benefit.

While The Sisters K is compelling from a psychological perspective, it is also fundamentally riveting and well-crafted from a storytelling perspective. More than any other book in recent memory, I read it, compulsively, to find out what happened next. Even if you have read the source material, you won't predict the events of the climax and last act. Like Dostoevsky's masterpiece, it's a plot that goes heavy on twists while maintaining credibility. And the ending largely satisfies—while everyone may not get exactly what they deserve, Sun demonstrates that the small, vicious, petty people will generally be undone by their own meanness and reap the loneliness they sowed with their cruelty.

With realistic and layered characters—Sarah and Minah are especially complex and vivid, but readers who have experience with a controlling, narcissistic, dictatorial man will be disturbed by the authenticity of Eugene—and a story that quietly simmers with intrigue until it boils over spectacularly, The Sisters K is an arresting portrait of rage, resentment, trauma, and revenge.

Book reviewed by Lisa Butts

Maureen Sun's The Sisters K was published by Los Angeles-based independent publisher Unnamed Press. Founded in 2014 by Chris Heiser and Olivia Taylor Smith, Unnamed Press was intended to be a publisher for international voices and translated literature but has since moved into domestic fare. The Press declares itself "committed to publishing a kaleidoscope of works that challenge the status quo," and in practice this means they have published some exceedingly strange and wonderful books over the past ten years. Their bare-bones staff includes Brandon Taylor (author of The Late Americans, 2023, and Real Life, 2020) as (seemingly the only) Acquisitions Editor, and Art Director Jaya Nicely churning out what is arguably some of the best cover art in the business.

Maureen Sun's The Sisters K was published by Los Angeles-based independent publisher Unnamed Press. Founded in 2014 by Chris Heiser and Olivia Taylor Smith, Unnamed Press was intended to be a publisher for international voices and translated literature but has since moved into domestic fare. The Press declares itself "committed to publishing a kaleidoscope of works that challenge the status quo," and in practice this means they have published some exceedingly strange and wonderful books over the past ten years. Their bare-bones staff includes Brandon Taylor (author of The Late Americans, 2023, and Real Life, 2020) as (seemingly the only) Acquisitions Editor, and Art Director Jaya Nicely churning out what is arguably some of the best cover art in the business.

Unnamed Press publishes fiction, nonfiction, and poetry titles, and its annual output has increased gradually since 2014. It published 16 titles in 2024, including The Sisters K and But the Girl. Other titles from this year include Henry, Henry by Allen Bratton, a contemporary queer take on Shakespeare's Henriad, and a history of publishing called The Untold Story of Books by Michael Castleman. The back catalog features an eclectic blend of works, from the Press's first published title, a novel about a Nigerian geologist on a mission to steal a piece of the moon (Deji Olukotun's Nigerians in Space, 2014), to a sociological exploration of gay cruising throughout history (Alex Espinoza's Cruising, 2019).

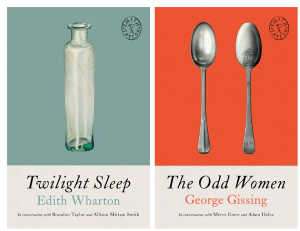

In 2024, Unnamed Press launched its Smith & Taylor imprint, which reprints classic forward-thinking novels that are "underappreciated" (with cover art featuring fantastic minimalist illustrations of everyday objects against brightly colored backgrounds). The imprint's first releases include Edith Wharton's Twilight Sleep, about a woman chafing against the strictures of "modern" motherhood and marriage in the 1920s, and George Gissing's The Odd Women, an early feminist novel about two sisters who defy traditional gender norms in Victorian-era London.

In 2024, Unnamed Press launched its Smith & Taylor imprint, which reprints classic forward-thinking novels that are "underappreciated" (with cover art featuring fantastic minimalist illustrations of everyday objects against brightly colored backgrounds). The imprint's first releases include Edith Wharton's Twilight Sleep, about a woman chafing against the strictures of "modern" motherhood and marriage in the 1920s, and George Gissing's The Odd Women, an early feminist novel about two sisters who defy traditional gender norms in Victorian-era London.

In addition to books, Unnamed Press produces vinyl recordings of audio works by some of its authors. For example, one can purchase James Elkins' novel Weak in Comparison to Dreams, about a scientific researcher studying zoos while experiencing a series of unsettling nightmares, or one can purchase a vinyl recording of the author reading selections from it over "original piano variations of sheet music that appear in the novel." In some cases, books and vinyl recordings are sold together in bundles.

Unnamed Press stands out in the publishing industry for its clear artistic vision and careful curation of interesting projects by a diverse roster of authors, but also genuinely unique product offerings like those listed above. It also co-owns, with independent press Rare Bird, a bookstore in Highland Park, California called North Figueroa, opened in November 2022.

by Julie Sedivy

If there is one feature that defines the human condition, it is language: written, spoken, signed, understood, and misunderstood, in all its infinite glory. In this ingenious, lyrical exploration, Julie Sedivy draws on years of experience in the lab and a lifetime of linguistic love to bring the discoveries of linguistics home, to the place language itself lives: within the yearnings of the human heart and amid the complex social bonds that it makes possible.

Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love follows the path that language takes through a human life―from an infant's first attempts at sense-making to the vulnerabilities and losses that accompany aging. As Sedivy shows, however, language and life are inextricable, and here she offers them together: a childish misunderstanding of her mother's meaning reveals the difficulty of relating to other minds; frustration with "professional" communication styles exposes the labyrinth of standards that define success; the first signs of hearing loss lead to a meditation on society's discomfort with physical and mental limitations.

Part memoir, part scientific exploration, and part cultural commentary, this book epitomizes the thrills of a life steeped in the aesthetic delights of language and the joys of its scientific scrutiny.

From an infant's first attempts to connect with the world around them to the final words shared with the dying, human life and language are intimately intertwined. Linguist Julie Sedivy's new book, Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, explores this connection through a fascinating combination of linguistic science and the author's own life story.

The book is divided into three parts. In the first part, "Childhood," Sedivy discusses how humans develop language as children, including how infants can recognize patterns in their native tongue long before they understand its meaning, and how children make judgement calls about who to trust when learning based on "constant testing." The science is accompanied by Sedivy's memories of her own childhood language adventures and misadventures: growing up immersed in multiple languages, first as a refugee in Europe and then as an immigrant in Canada; running away from what she thought were giant rabbits due to her then shaky grasp of Italian; being mad at her mother after a miscommunication (when young Julie asked her if she was pretty, her mom responded, "It's more important to be smart than pretty"). Sedivy's ability to connect personal experiences to scientific research—and to explain the science in a clear and understandable way—makes for a compelling read.

In the second section, "Maturity," Sedivy focuses on adult life, including the ways in which adults manage uncertainty and time while talking, unconsciously extrapolating possible conclusions to words and sentences as they listen. In one of the studies she conducted, she used a device to track subjects' eyes as they heard the sentence "Pick up the candle": the subjects often glanced at a candle midway through the final word, but had no memory of doing so, or of considering the candle at all, when they were interviewed after the session. Sedivy links this split-second consideration to the end of her first marriage—a short, tumultuous period in which her life could have gone in two very different directions before resolving into the path she chose. She also explores, here, the pleasure she takes in beautiful language. "Beautiful words cause my saliva to run," she writes. "I suck on them like fruit drops."

"Maturity" also expands outwards into societal topics and complexities, not just personal ones. As a female academic, Sedivy has experienced her fair share of sexism and shares in her book her struggle to be taken seriously as a woman in science; for example, she once overheard a conversation suggesting that her pregnancy indicated a lack of dedication to her career. She also shares her thoughts on why "speaking for success" is not as simple as people think—partly because different people apply multiple standards to success based on their own life experiences—and on the trend in publishing for "plain speech," a style that pares down wordy language, like that of Marcel Proust or Henry James, which can be more difficult to understand, but is often beautiful because of its intricacy.

The final section, "Loss," deals with the effects of aging on speaking and hearing—both positive, such as a widely expanded vocabulary, and negative, such as hearing loss and its isolating social effects, as those affected are less able to follow and participate in conversations. Sedivy also reflects on her own aging and the losses she has experienced, including her changing relationship with her father's memory and an incredibly moving account of her brother's death.

As Sedivy points out, language is about connecting people, so it's fitting that the memoir sections of Linguaphile are focused more on the relationships in her life than on specific events. She explores both the good and the bad in her connections with her parents, husbands, siblings, and friends, and in doing so, evokes the compelling complexity of human life. The titular love of language, as well, is apparent throughout the book; Sedivy explores both the science and the beauty of language in a way that celebrates both, and in a way that will make the reader pause to reflect on her own experiences of language and connection.

Book reviewed by Katharine Blatchford

In Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, a combination of popular science and memoir, linguist Julie Sedivy shares that one of her worst fears is that an illness or injury will cause her to develop aphasia, a type of disorder that impacts a person's ability to use both spoken and written language. After this confession, she goes on to describe the experiences of Paul West, a prolific author who struggled with this very disorder. Born in 1930, West published a wide variety of work, including novels, essays, and literary criticism, in addition to teaching at multiple universities. In 2003, West had a stroke which damaged areas of his brain key to the processing of language, causing global aphasia, the most severe form. Immediately after the stroke, he was only able to use a single syllable—mem. After three weeks in the hospital, he had regained some basic vocabulary, and continued speech therapy helped him reclaim more.

In Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, a combination of popular science and memoir, linguist Julie Sedivy shares that one of her worst fears is that an illness or injury will cause her to develop aphasia, a type of disorder that impacts a person's ability to use both spoken and written language. After this confession, she goes on to describe the experiences of Paul West, a prolific author who struggled with this very disorder. Born in 1930, West published a wide variety of work, including novels, essays, and literary criticism, in addition to teaching at multiple universities. In 2003, West had a stroke which damaged areas of his brain key to the processing of language, causing global aphasia, the most severe form. Immediately after the stroke, he was only able to use a single syllable—mem. After three weeks in the hospital, he had regained some basic vocabulary, and continued speech therapy helped him reclaim more.

He went on to publish four more books before his death in 2015. The first was The Shadow Factory, a memoir published in 2008. In it he discusses his experience of aphasia:

"There was a bewildering assortment of false starts and incomplete sentences for the mind only. I no sooner thought of something to say to myself than I forgot it, and I was lucky to get beyond the second or third imagined word. Of course no one in his right mind overheard any of this, the dumb speaking to the silent in a reverse image, so no one was upset. But if this happens 50 or 60 times, one wants a little revenge of some sort."

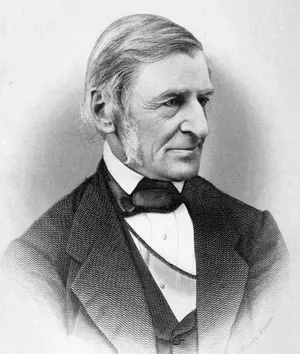

Paul West is not the only writer to face the challenge of losing language abilities; one of the most famous was Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson was leader of the 19th century transcendentalist movement, and an incredibly influential lecturer, essayist, and poet. He first began experiencing aphasia at the age of 64, possibly after a stroke. Despite the distress and frustration this caused him, he continued working for five more years before retiring at the request of his daughter, Ellen. After retirement he traveled both within the United States and abroad to Europe and Egypt, and occasionally still gave talks to smaller audiences. In his later years, he is quoted as telling people that he was, "Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well."

More recently, in 2022 Tony award winner and Pulitzer Prize finalist Christopher Durang announced his diagnosis of logopenic primary progressive aphasia (PPA), caused by a rare form of Alzheimer's disease that first affects language skills rather than memory. Over a career of more than four decades, Durang earned a reputation for brilliant satire and dark comedy. He began experiencing symptoms in 2012, which gradually worsened over time.

In an interview with Broadway News, Durang's husband, John Augustine, compared the playwright's experience to that of someone who is able to speak Spanish, but not fluently:

"If people come up to you and start talking quickly in Spanish and want you to answer or explain something technical to them, you know what that feeling is. You're not out to lunch. You know what you want to say; you just don't know the words. If people interrupt you or try to answer for you, that throws you off."

Durang died in April of 2024, from complications of his disease.

Language is central to all of our lives, and aphasia can be difficult to imagine for those not affected by it. By sharing their experiences, these writers have allowed others to get a better picture of the reality of aphasia. As the National Aphasia Association noted after Durang's announcement, "this type of coverage is priceless in helping people better understand the condition and how they can support someone with aphasia."

by Maame Blue

On the cusp of thirty, Ghanaian Londoner Whitney Appiah was born with a special gift. The massage therapist can physically sense where her clients' trauma lies and heal them. But Whitney has no idea that she too, is suffering. Tragic events from her youth have left a terrible, unseen mark. When a dangerous encounter with the man she's dating triggers a wave of fragmented recollections, Whitney embarks on a journey to reclaim her memories and the truth that is buried deep in her early years growing up in Kumasi, Ghana during the 1990s.

Spanning three decades, told through the viewpoints of Whitney, sisters Gloria and Aretha, and their house help Maame Serwaa, The Rest of You explores what happens when we try to move forward through the lacuna of our past.

A strikingly original novel inspired by the Twi proverb of Sankofa: looking back in order to move forward, The Rest of You is a story of generational healing, what it means to be Black British, and surviving familial migrant journeys. Tackling darkly serious themes yet full of hope and optimism, and told with an eye towards the future, Maame Blue's extraordinary tale is an unforgettable celebration of womanhood, friendship, and family.

At the start of Maame Blue's The Rest of You, Whitney Appiah, a Ghanaian Londoner, is ringing in her thirtieth birthday at a bar with her best friend and roommate, Chantelle. However, she is also reeling from a recent surprise phone call from a man she was dating, which has triggered memories of a traumatic night with him that she has been trying to suppress. As a masseuse, she knows all the ways the body communicates and holds onto feelings. She knows how to heal others, but she is struggling to heal herself. With recurring childhood nightmares now returned and affecting her deeply, the weight of painful recollections and unanswered questions about her family history leads her to finally confront her Aunt Gloria, who has been keeping crucial parts of her past a secret.

The Rest of You spans three decades. We follow Whitney in present-day London, and her aunts Gloria and Aretha along with their house help, Maame Serwaa, in 1995 Kumasi, Ghana, learning about the family's history of tragedy and grief. Aunt Gloria has filled the role of Whitney's sole guardian since both her parents died. Gloria's youngest sister Tina died giving birth to Whitney, and Gloria has told Whitney that her father died from an unknown illness. But we learn through the POVs of Gloria, Aretha, and Maame Serwaa that Bobby, Whitney's father, was killed by a friend of his, and despite her lack of recollection, Whitney, as a toddler, witnessed his death.

Blue has crafted an artful story through which to explore the themes of grief, generational trauma, male violence (toward other men and women), friendships, and family. She examines the ways Whitney's aunt, trying to protect her from pain, has inflicted more harm by limiting the knowledge she has of her parents and where she comes from. This has shaped her identity, how she makes sense of herself, and how she handles her relationships with others:

"Naturally, you had become a quietly curious person because of it, always hovering in between the gaps of things you didn't know about yourself. You rarely asked questions out loud anymore, even when questions constantly ran through your mind, even when you wondered why people did the things they did, why they hurt each other — or you."

The third-person voice is used for all the characters except Whitney, whose perspective is related in the second person. This is a unique and intelligent way to place you in her point of view that I felt was effective in creating empathy for her character.

One of the greatest benefits of multiple perspectives in a story is understanding different people's decisions. Seeing the juxtaposition of how the characters perceive each other's actions is poignant. Chapters alternate between Whitney, her aunts, and Maame Serwaa, making evident how they view each other's mindsets and how they have navigated the loss of loved ones. This structure showcases how, with family, there are often misunderstandings, and there are differences between the narratives we believe to be true about our choices and how others see them. Aretha felt Gloria was being irrational in moving away from the family to London with Whitney, and Gloria felt Aretha was being selfish in not following. While Whitney feels Gloria has been wrong in withholding information about her parents and their home in Ghana, Gloria has felt that it is the only way to move forward because of grief and the fear of a family curse. Whether or not you agree with Gloria's decision, it is humanizing to see how pain and trauma have shaped it.

Whitney's relationship with her two best friends, Chantelle and Jak, further illuminates Blue's theme of male violence and how it affects identity and womanhood. (Anyone with sensitivity toward sexual assault should be cognizant of its presence in this storyline, which I felt Blue handled with authenticity and care.) It also shows how friendships can be as important to us as family. Whitney has no siblings, so outside of her Aunt Gloria, Chantelle and Jak have been her support system. All of them deal with trauma from relationships with men involving sexual violence, on top of various growing pains that seep into how available and present they can be for each other, and it is moving to see how Blue navigates conflict between the three and portrays the moments they support and show each other grace and empathy.

While Blue successfully explores the story's themes, some readers may feel the suspense around the plot point of Whitney's father's death, which comes with ambiguity and a lack of closure, leaves something to be desired. However, I believe the intentional choice to withhold answers reinforces a lesson the characters learn: Nothing will fill the gap of the death of someone you love.

Blue's choice to begin the story with Whitney's thirtieth birthday and end it on her thirty-first is a crafty move that compels readers to reflect on the character's development. There is a recurring push and pull between the desire to look forward and the desire to look back on life. Still, the repeated mention of a Sankofa proverb, "We need to know our past in order to look to the future," emphasizes the idea I believe Blue wants readers to take away.

The Rest of You is an engaging, emotional journey that tackles heavy themes while remaining hopeful. Readers who enjoy literary fiction involving family, friendship, trauma, and grief will find this a satisfying and memorable read.

Book reviewed by Letitia Asare

There are many different tribes and cultural influences in Ghana; therefore, Ghanaian culture shouldn't be assumed to be a monolith. However, the tradition of naming children after the day they are born is a common practice in the country. It originates from the Akan people — the largest ethnic group in Ghana, making up 47.3% of the population — and is present throughout West Africa and the African diaspora.

There are many different tribes and cultural influences in Ghana; therefore, Ghanaian culture shouldn't be assumed to be a monolith. However, the tradition of naming children after the day they are born is a common practice in the country. It originates from the Akan people — the largest ethnic group in Ghana, making up 47.3% of the population — and is present throughout West Africa and the African diaspora.

The tradition names children after the day of the week they are born and birth order (with designated additional names given if siblings are born on the same day of the week, or are twins). The names have a deeper meaning connected to the soul and character of the person, similar to the more widespread symbolism of astrological signs. Most Ghanaians have at least one name from this tradition, even if they also have an English name.

In The Rest of You by Maame Blue, several characters are referred to by their day names.

"Mabel always emphasized Aretha's day name — given because of her Monday birth and assumed peaceful nature — like it was something special, a thing to be handled delicately."

"Bobo, that name you couldn't bear to hear from anyone who wasn't Ma Gloria. An approximation of Abena, your day name — Tuesday-born — that you couldn't pronounce when you were a child…"

Names for the seven days follow this basic system, though variations exist:

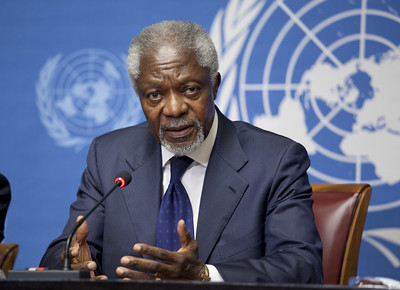

A few notable examples of people with day names include Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana's first president, Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, and Ama Ata Aidoo, a Ghanaian author, poet, politician, and academic. The "Ata" in Aidoo's name refers to her status as a twin sibling.

Names carry significance and meaning for many people worldwide, including Ghanaians. As seen in The Rest of You, they can have ripple effects on a child's identity and help them and others gain more insight into who they are as individuals.

Joint Special Envoy Kofi Annan Speaks With Press After Meeting of Action Group for Syria (June 30, 2012)

Courtesy of United States Mission Geneva (CC BY-ND 2.0)

by Kate Greathead

If you haven't had the misfortune of dating a George, you know someone who has. He's a young man brimming with potential but incapable of following through; sweet yet noncommittal to his long-suffering girlfriend; distant from but still reliant on his mother; charmingly funny one minute, sullenly brooding the next. Here, Kate Greathead paints one particular, unforgettable George in a series of droll and surprisingly poignant snapshots of his life over two decades.

Despite his failings, it's hard not to root for George at least a little. Beneath his cynicism is a reservoir of fondness for his girlfriend, Jenny, and her valiant willingness to put up with him. Each demonstration of his flaws is paired with a self-eviscerating comment. No one is more disappointed in him than himself (except maybe Jenny and his mother). As hilarious as it is resonant and as singular as it is universal, The Book of George is a deft, unexpectedly moving portrait of one man―but also countless others.

The premise of The Book of George, the witty, highly entertaining new novel from Kate Greathead, is that every reader knows a George. Well-heeled and well-connected, he's a young man with all of life's doors open to him—and a young man who systematically fails to walk through a single one. He's got smarts, but he's too lazy to use them; he's got a loving girlfriend, but he's too self-absorbed to commit. From early adolescence to the cusp of middle age, we follow this eponymous hero in episodic chapters plucked from a life emblematic of stagnating millennial masculinity.

Wasted potential and failure to follow through unite the fragments of George's story. After choosing last minute to major in philosophy, he drifts from one short-term endeavor to the next, trying his hand at everything from hedge fund intern to high-end dog walker to TV commercial actor. Greathead cleverly plays on the idea of the picaresque hero (see Beyond the Book), a loveable rogue satirizing society's mores as he slips from one adventure to the next. In her modern writing of the genre, George is the butt of the joke. Even as Jenny, his long-suffering girlfriend, wants to start getting serious about their relationship, this disaffected 21st-century pícaro can't help but shake off the foundations of a happy, stable life.

Whether one can share in Jenny's (somewhat begrudging) love of George will depend on their patience. What's certain is that he's a permanent frustration to those around him—not least the reader. Yet this is far from a failure of the novel; in fact, it's the book's great success. Greathead has painted a strikingly relatable portrait of, as she calls him, "a benign asshole." He can be funny and tender, but also pig-headed, idle, and maddeningly inconsiderate. (That he readily admits to these flaws leads him to think he has permission to indulge in them.) By far George's most impressive quality is how true to life he feels on the page. It takes no mean skill to craft a character whose foibles and fixations are so recognizable in friends, family, or—most unsettling of all—the reader himself.

Greathead's writing on the whole is quick and cutting, with something of the terse black wit of Kurt Vonnegut. "A plane crashed into a tower of the World Trade Center," she writes plainly. "And then another plane crashed into the other tower." It's a style that ensures George's life skips along at an enjoyable clip, but one which sadly doesn't lend itself to the level of depth the author at times aims for. George's picaresque adventures cut through some of the great social upheavals of the last two decades—Occupy Wall Street, MAGA, the MeToo movement—but the novel's fast-paced episodes mean that too often these feel more like superficial waypoints through the 21st century than cultural moments worthy of true reflection.

Greathead's strengths instead lie in the witty back-and-forth of her dialogue and the unspoken conflict tangled beneath. Indeed, tragedy underlies the "sitcom-level banter" that comes so naturally to George; having lost his father at an early age, grief has led him to retreat into himself. But Jenny too is no stranger to childhood trauma, and her continued thoughtfulness and determination feel like a pointed rebuttal. Why does she thrive while her boyfriend wallows in lazy self-absorption? One old friend pierces to the heart of the matter: "You're a privileged white guy who grew up thinking you were God's gift." But now, to succeed in the shifting power dynamics of the new century, Greathead shows that young men like George might actually have to start matching the efforts of the less privileged. And like so many of his generation, he steps up to this challenge with a mixture of bewilderment, resentment, and inertia.

Though the satire may be biting, it is never damning. Greathead is a gifted storyteller who fills The Book of George with joyous humor and small, heartfelt moments that hint at its hero's redemption, or at least its possibility. After all, there must be some reason Jenny sticks with him—and it's the emotional thread of that decades-long relationship that will pull readers through the twists and turns of this charming novel. In the end, that may be George's most redeeming feature: that so often he has someone like Jenny fighting his corner.

Book reviewed by Alex Russell

In The Book of George, Kate Greathead covers the life of her eponymous hero in 14 chapters depicting key moments from his first 40 years. In doing so, she draws on elements of the picaresque, an episodic literary genre in which an outsider moves from adventure to adventure while satirizing the society of the day.

In The Book of George, Kate Greathead covers the life of her eponymous hero in 14 chapters depicting key moments from his first 40 years. In doing so, she draws on elements of the picaresque, an episodic literary genre in which an outsider moves from adventure to adventure while satirizing the society of the day.

The picaresque is one of the earliest forms of the novel. It originated in 16th-century Spain during the country's "Golden Age," and is believed to have drawn from diverse influences such as Apuleius's The Golden Ass (the only Roman novel to survive in its entirety) and the Arabic Maqāmāt literature of Islamic Spain. In time, the genre evolved as a counterpoint to existing chivalric romance. Instead of recounting the heroic deeds of knights, however, picaresque novels followed a loveable rogue—the Spanish word pícaro can be translated as "rogue"—who uses his wits to succeed in an unjust world.

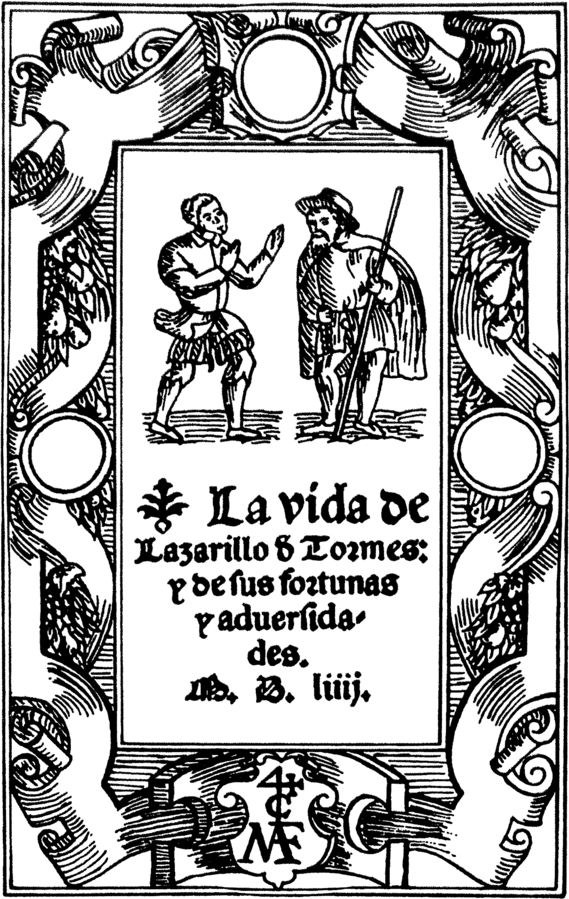

The genre is generally considered to have its first recognizable expression in the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes from 1554, in which the young Lazarillo serves various religious masters and exposes the hypocrisy of the Church. One of the first Spanish literary works banned by the Inquisition, Lazarillo would see a plethora of imitators appear at the turn of the next century. Most influential among these was Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote (1605). Although not picaresque in the strictest definition, the episodic nature of the novel and its social satire are undeniably marked by the popularity of pícaro tales in the Spanish Golden Age.

From Cervantes, the picaresque traveled north over the Pyrenees and east over the Atlantic to the New World. While the appeal of this plotless, episodic genre waned over the centuries in favor of more linear narratives, classic works of literature continued to rely on its key elements: The History of Tom Jones and Moll Flanders in the 18th century, Vanity Fair and The Pickwick Papers in the 19th. Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, with its rascally, street-smart protagonist, owes more than a little to Cervantes and the Spanish picaresque.

Given the wide range of literary works spread across centuries and continents that deploy picaresque elements, it's little wonder that scholars hotly debate the scope and shape of the genre. As the academics John Kent and J. L. Gaunt put it bluntly, "no one seems to know precisely what is picaresque and what is not." Several key characteristics, however imperfect, have nevertheless been proffered over the years: e.g., first-person narration, strict realism, social satire, a protagonist of low station, and a struggle for existence in a hostile and chaotic world.

Kate Greathead's The Book of George clearly does not comply with all these usual characteristics of the genre. Most glaringly of all, George comes far from any low station in life. However, one might be able to read playful satire in this inversion of generic convention: in many ways, Greathead applies the picaresque to reveal a central flaw in modern masculinity. After all, it speaks to George's absurdity that, born with all the privilege of a well-connected white male in the richest nation on Earth, he still can't help thinking of himself as one of life's victims—a lonely pícaro on the margins of society.

Title page for Lazarillo de Tormes (Impresor Mateo y Francisco del Canto, 1554), via Wikimedia Commons

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.