Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

At night I told myself a story, wordless, inside my head, one I liked

far better than those in my books. The girl in my story was treated

cruelly, by fate, by her family, even by the weather. Her feet bled from

the stony paths; her hair was plucked from her head by blackbirds. She

went from house to house, looking for refuge. Not a single neighbor

answered his door, and so one day the girl gave up speaking. She lived

on the side of a mountain where every day was snowy. She stood outside

without a roof, without shelter; before long she was made of ice—her

flesh, her bones, her blood. She looked like a diamond; it was possible

to spy her from miles away. She was so beautiful now that everyone

wanted her: people came to talk to her, but she wouldn't answer. Birds

lit on her shoulder; she didn't bother to chase them away. She didn't

have to. If they took a single peck, their beaks would break in two.

Nothing could hurt her anymore. After a while, she became invisible,

queen of the ice. Silence was her language, and her heart had turned a

perfect pale silver color. It was so hard nothing could shatter it. Not

even stones.

"Physiologically impossible," my brother said the one time I dared to

tell him the story. "In such low temperatures, her heart would actually

freeze and then burst. She'd wind up melting herself with her own

blood."

I didn't discuss such things with him again.

I knew what my role was in the world. I was the quiet girl at school,

the best friend, the one who came in second place. I didn't want to draw

attention to myself. I didn't want to win anything. There were words I

couldn't bring myself to say; words like ruin and love and

lost made me sick to my stomach. In the end, I gave them up

altogether. But I was a good grandchild, quick to finish tasks, my

grandmother's favorite. The more tasks, the less time to think. I swept,

I did laundry, I stayed up late finishing my homework. By the time I was

in high school, I was everyone's confidante; I knew how to listen. I was

there for my friends, a tower of strength, ever helpful, especially when

it came to their boyfriends, several of whom slept with me in senior

year, grateful for my advice with their love lives, happy to go to bed

with a girl who asked for nothing in return.

My brother went to Harvard, then to Cornell for his graduate degree;

he became a meteorologist, a perfect choice for someone who wanted to

impose logic onto an imperfect world. He was offered a position at Orlon

University, in Florida, and before long he was a full professor, married

to a mathematician, Nina, whom he idolized for her rational thought and

beautiful complexion. As for me, I looked for a career where silence

would be an asset. I went to the state university a few towns over, then

to City College for a master's in library science. My brother found it

especially amusing that my work was considered a science, but I took it

quite seriously. I was assigned to the reference desk, still giving

advice, as I had in high school, still the one to turn to for

information. I was well liked at the library, the reliable employee who

collected money for wedding presents and organized baby showers. When a

co-worker moved to Hawaii I was persuaded to adopt her cat, Giselle,

even though I was allergic.

But there was another, hidden side to me. My realest self. The one

who remembered how the ice fell down, piece by bitter piece. The one who

dreamed of cold, silver hearts. A devotee of death. I had become

something of an expert on the many ways to die, and like any expert I

had my favorites: bee stings, poisoned punch, electric shock. There were

whole categories I couldn't get enough of: death by misadventure or by

design, death pacts, death to avoid the future, death to circumvent the

past. I doubted whether anyone else in the library was aware that rigor

mortis set in within four hours. If they knew that when heated, arsenic

had a garlic-like odor. The police captain in town, Jack Lyons, who'd

been in my brother's class in high school, often called for information

regarding poison, suicide, infectious diseases. He trusted me, too.

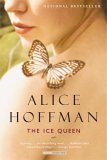

From The Ice Queen, pages 3-31 of the hardcover edition. Copyright © 2005 by Alice Hoffman. Reproduced with the permission of Little, Brown & Co.

A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas--a place ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.