Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Bad news had been filtering into the valley every day for the last few weeks.

First the failed landings in Normandy. Then the German counterattack. The pages

of the newspapers were dark with the print of the casualty lists. London was

swollen with people fleeing north from the coast. They had no phone lines this

far up, and apart from Maggie's farm, which sat higher in the valley, the whole

area was dead for radio reception. But news of the war still found its way to

them. The papers, often a couple of days old, the farrier when he came, Reverend

Davies on his fortnightly visits to The Court, all of them brought a trickle of

stories from the changing world beyond the valley. Everyone was unnerved but

Sarah knew these stories had unsettled Tom more than most. He rarely spoke of

it, but for him they threw a shadow in the shape of his brother, David. David

was three years younger than Tom. He'd had no farm of his own so he'd been

conscripted to fight. Two months ago he was declared missing in action and,

while Tom maintained an iron resolve that his brother would appear again, the

sudden shift in events had shaken his optimism.

For Sarah news of the war still seemed to have an unreal quality, even when a

few days ago the names of the battlegrounds changed from French villages to

English ones. There were marks of the conflict all about her: the patchwork of

ploughed fields down by the river once kept for grazing; the boys from her

schooldays, and the farmhands, many of them gone for years now. But unlike Tom

she didn't have a relative in the fighting. Her own older brothers had been

absent from her life ever since they'd argued with her father and broken from

the family home when she was still a girl. They'd bought a farm together outside Brecon, large enough to have saved them both from the army. So Sarah didn't

possess that vital thread connecting her to the war that brought the news

stories so vividly to life for so many others. There were women here, in the

valley, who had lost sons, and in the early years she'd seen other mourning

mothers and wives in Longtown and Llanvoy. But even these women, with their

swollen eyes and dark dresses, seemed to have passed into a different place, a

parallel world of grief. The sight of them evoked sympathy in Sarah, sometimes a

flush of silent gratitude that Tom was in a reserved occupation, but never

empathy.

Only once in the last five years had the war really impacted upon her. When the

bomber crashed up on the bluff. Then, suddenly, it had become physical. She'd

been woken by the whine of its dive followed by the terrible land-locked thunder

of its explosion. Tom held her afterwards, speaking softly into her hair, “Shh, bach, shh now.” In the morning they'd all gone up to look. Tom and she took the

ponies. When they got there the Home Guard and the police from Hereford had

already put a cordon around the wreckage so they just stood at a distance and

watched, the thin rope singing and whipping in the hilltop wind. Beyond the

crashed plane she'd glimpsed a tarpaulin laid over a shallow hump. “One of the

crew,” Tom had said with a jerk of his chin. She'd agreed with him. “Yes, must

be,” although she'd thought the hump looked too small, too short, to be the body

of a man. The ponies shifted uneasily under them, pawing the ground, tossing

their heads. They were disturbed by this sculpture of twisted metal that had

appeared on their hill, by this charred and complicated limb half embedded in

the soil as if it had erupted from the earth, not fallen from the sky. And so

was Sarah. She'd heard about the Blitz, and about Liverpool and Coventry, its

cathedral burning through the night. She'd even seen their own bombers out on

training runs. But she'd never seen an enemy plane before. Usually they were

just a distant drone to her, a long revolving hum above the clouds as they

returned from a raid on Swansea or banked for home after emptying their payloads

over Birmingham. But now, here was one of them, on the hill above her farm.

Massive and perfunctory. So ordinary in its blunt engineering. And under that

tarpaulin was a real German. A man from over there who had flown over here to

kill them.

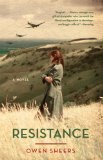

Excerpted from Resistance by Owen Sheers Copyright © 2008 by Owen Sheers. Excerpted by permission of Nan A. Talese, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.