Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

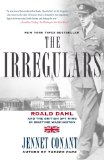

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

Even though Dahl took the game too far, at times openly flaunting authority, his confidence and air of infallibility made him seem unassailable. "Roald could be like sand in an oyster," recalled Dahl's first wife, the actress Patricia Neal. "He seemed to feel he had the right to be awful and no one should dare counter him. Few did."

As Antoinette observed, "In a game of one-upmanship, it was hard to top Roald. He got away with a lot. He was always sarcastic, but sometimes he was very rude, and he could be cruel, and that got him into trouble."

Whether officials at the embassy eventually tripped to his prank correspondence or simply tired of his antics, Dahl came in for disciplinary action and was warned that he could be shipped back to England at a moment's notice. Aware that he was under review and that his dismissal was most likely inevitable, Dahl decided he had better take preemptive action. He began checking his options and investigating other avenues of employment. "I started nosing around a little bit," he recalled. "There were all sorts of things going on in Washington." So many British information services and press agencies had set up shop in the United States, and there were so many different bureaus, departments, and divisions -- most of them a complete waste of time and energy had they not been some sort of front organizations -- that there was no shortage of opportunities. Add to that the confusion of fledgling intelligence organizations, including the British-American cooperative effort recently christened the OSS, which everyone in Washington jokingly called "Oh So Secret" or "Oh So Silly." Something was bound to turn up.

"It was a very strange, chaotic time," said the writer Peter Viertel, a marine officer assigned to the OSS, who met Dahl in Washington while receiving some additional training before being sent to France to infiltrate German lines. "You couldn't tell what anyone was really doing, or who they were really working for. There were all these government agencies which had been formed, with all these different branches, full of people who were theoretically doing something for the war. You got the feeling a lot of those people were quite happy to be in those jobs, where there wasn't a lot of trouble."

It was at this unsettled moment in his life that Dahl first fastened on the idea of trying something outside normal channels. He had heard rumors about a sort of unofficial branch of the services that might be willing to take on someone like him. It was an organization that fell under the umbrella of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, also known as MI6). No official title had been given to this cloak-and-dagger outfit, and for that matter no prior War Cabinet approval. It was called BSC by default, after the original Baker Street address of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in London, but the initiated preferred to think of it as a reference to Sherlock Holmes's "Baker Street Irregulars." It had been formalized as the British Security Coordination, a title created arbitrarily by the American FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who was not raised on Arthur Conan Doyle and did not share the English enthusiasm for code names. The BSC's American headquarters were in Rockefeller Center in New York, and the shadowy figure who ran it was a wealthy Canadian industrialist turned professional saboteur by the name of William Stephenson, who had the title of director of British Security Coordination and was head of the Secret Intelligence Service in the Western Hemisphere. Those in the know sometimes referred to him as intrepid, after the BSC's Manhattan cable address. "I knew who he was," recalled Dahl. "Not when I first arrived in Washington, but I very soon realized that everybody in any position of power either from the British ambassador down or on the American side knew about this extraordinary fellow."

Stephenson had been dispatched to America by Churchill after the nightmarish winter of 1940, during which Mussolini joined forces with Hitler, German bombs rained down on Britain's cities, and the enemy waited only twenty miles from their shores. As morale in Britain plummeted to its lowest point, Churchill concluded that England's only chance of survival depended on the United States' entry into the war. England had to find a way to contrive that intervention -- whatever it took. America's continued isolationism would be the death of them. If the United States was to be persuaded of the utmost importance of the British cause and pushed into action, then the isolationists -- the antiwar lobby, Lindbergh's America Firsters, and the Nazi-run fifth columnists -- would have to be systematically undermined and eliminated. British intelligence would need a sophisticated network of agents on the ground to orchestrate the interventionist effort, and to supply propaganda that would promote fears of a direct German threat to the United States and prod the reluctant American people into supporting the war.

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.