Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

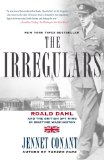

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

With barely a year's worth of formal training, Dahl was made a pilot officer and judged ready to join a squadron and face the enemy. He was sent to Libya to fight the Italians, who were attempting to seize control of the Mediterranean and were amassing their forces prior to advancing into Egypt. He made his way to Abu Sueir, a large RAF airfield on the Suez Canal, where he was given a Gladiator, an antiquated single-seat biplane that he had absolutely no idea how to operate, and told to fly it across the Nile delta to a forward base in the Western Desert, stopping twice to refuel along the way and receive directions to his new squadron's whereabouts. Needless to say, he never made it. Lost and low on fuel, he made what the RAF squadron report termed "an unsuccessful forced landing" and crashed headlong into the desert floor at seventy-five miles on hour. Despite the impact, he remained conscious long enough to free himself from his seat straps and parachute harness and drag himself from the fuselage before the gas tanks exploded. His overalls caught fire, but he somehow managed to smother the flames by rolling in the sand and suffered only minor burns. Luckily for him, he was picked up not long afterward by a British patrol that spotted the wreck and, when darkness fell, sneaked into enemy territory to check for survivors. All in all, it was a very close call.

Dahl was sent to a naval hospital in Alexandria, where he spent six months recovering from a severe concussion sustained when his face smashed into the aircraft's reflector sight. His skull was fractured, and the swelling from the massive contusion rendered him blind for weeks, and he suffered splitting headaches for months after that. His nose, which had been reduced to a bloody stump, was rebuilt by a famous Harley Street plastic surgeon who was out there doing his part for the war, and according to an informal poll of the nurses, Dahl's profile looked slightly better than before. The most lasting damage was done to his spine, which had been violently crunched in the collision and would never be entirely free of pain.

The entire time he was laid up in the hospital, Dahl could not wait to go back. It was not just the excitement he missed, though he had come to love flying. He had not been able to escape the feeling that he had failed everyone -- failed himself -- by ditching his plane on his very first trip to the front lines, and he was determined to redeem himself. The doctors had told him that in time his vision would clear, and the headaches would lessen, but the waiting was agony. Dahl was so worried about not being cleared for combat duty again that when informed that he was scheduled to return home on the next convoy, he refused to go. "Who wants to be invalided home anyway," he wrote his mother. "When I go I want to go normally."

It was a sign of just how badly the war was going that in April 1941, despite the injury to his head, he was cleared for operational flying. He was told to rejoin 80 Squadron, which was now in Greece. While convalescing in Alexandria, Dahl had kept up with the news and was aware that things were not going at all well for the token British expeditionary force that had been sent to Greece to repel the invading Italians. By the time the British decided to recall their army, the Italians had brought in German reinforcements, and as they rolled across the Greek frontier, the British found themselves outnumbered and outmaneuvered. Unless they could extricate their 53,000 troops in a hurry, it promised to be a bitter defeat, another Dunkirk in the making. Dahl realized that the two paltry RAF squadrons assigned to provide air cover for the retreat, of which 80 Squadron was one, were no match for the enemy and were being used as cannon fodder in an utterly hopeless and ill-conceived campaign. But he had his orders. There was nothing to do but get on with it.

Once again Dahl took off from Abu Sueir in an unfamiliar plane, a Mark I Hurricane, a powerful fighter with a big Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and eight Browning machine guns. This time, however, he managed to find his way north across the sea and landed safely on Elevsis, near Athens, less than five hours later. Almost immediately upon landing, his worst fears were confirmed when he learned that England was attempting to defend the whole of Greece with a total of eighteen Hurricanes, against a huge German air invasion force of well over one thousand Messerschmitt 109s and 110s, Ju 88s, and Stuka dive-bombers. Any dreams of glory Dahl had entertained while lying in his hospital bed vanished at the prospect of such daunting odds.

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.