Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

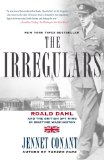

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

It had been expected that he would go on to university, to Oxford or Cambridge, but he had set his heart on adventure abroad. Mother and son were very close -- she had moved the whole family from Wales to England to be nearer his school -- and when he broke the news that he had signed a contract with the Shell Oil Company for a three-year tour in Africa, she had been careful not to betray any hint of emotion. He was more boy than man when he left, and he had been bursting with excitement and too full of thoughts of "palm-trees and coconuts and coral reefs" to feel any guilt as he waved a last farewell to his mother and sisters at the London docks. He had not known then that the war would intervene and that the three years would seem much, much longer -- more like a lifetime.

Dahl was not a demonstrative man, but after barely getting out of Egypt in one piece, he had been desperate to be reunited with his family. The harrowing journey home on the bomb-threatened troopship, which was chased by German submarines in the Atlantic, and by Focke-Wulf aircraft on the last leg of the voyage from Lagos to Liverpool, only heightened his sense of urgency. He had not had an easy time of it. After working so hard to overcome his injuries and return to his squadron, it had been a bitter pill to be grounded after barely a month. On top of his disappointment at being discharged was the disconcerting knowledge that the complications from his concussion were not completely behind him and would most likely bar him from any other frontline service in the war. It was hard to believe that his days of fighting Germans had come to such a quick end, harder still to take leave of his gallant comrades, who would continue with the squadron without him. When he said good-bye to his closest friend, David Coke, the Earl of Leicester's youngest son, who had been kind enough to show a green recruit the ropes, it was impossible not to wonder if they would ever see each other again.*

To keep his mother from worrying, Dahl had sent her a brief cable from Egypt telling her he was coming home, adding with false bravado that he was "very fit" and the Syrian campaign had been "fun." He still had not received any word from her when his ship sailed from Freetown for Liverpool, but mail service to Haifa was hardly reliable, and he had had no news from England for some time. As a consequence, he had a bad scare when he arrived at Liverpool and attempted to phone his mother's house in Kent, only to be told by the operator that the number was disconnected months ago. The operator had said, "She'll probably have been bombed out like all the rest of them," and speculated that she had moved elsewhere. An awful lot hung on that "probably." The confusion caused by the blitz, where family members were killed or injured in blasts, buried in rubble, or lost as they scrambled from one temporary shelter to another, made for a nightmarish twenty-four hours until he finally succeeded in tracking them down. It turned out that his mother and two of his sisters had been hiding in the cellar when their house was hit and had promptly packed the dogs and what was left of their belongings into the car and driven around the countryside until they had found a suitable cottage in Grendon Underwood. When the bus ferrying him to the tiny village finally pulled to a halt, Dahl spotted a familiar figure standing patiently by the road and, as he later wrote, "flew down the steps of the bus straight into the arms of the waiting mother."

He had been home only a few short months when he learned that the undersecretary for air planned to send him away again. Dahl had met Harold Balfour quite by chance that fall, when a colleague had invited him to dine at Pratt's, one of the better-known men's clubs in London. During the course of the evening, Dahl had done his best to impress the senior official with his battle stories and his skill at bridge. Balfour must have taken it upon himself to arrange a cushy assignment for the disabled flier, because the next day he summoned Dahl to his office and informed him that he would be joining the British Embassy in Washington D.C. as an assistant air attaché. When he heard the news, Dahl protested, "Oh no, sir, please, sir -- anything but that, sir!" Balfour would not be moved: "He said it was an order, and the job was jolly important."

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

There is no science without fancy and no art without fact

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.