Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

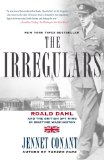

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

On March 24, 1942, the Foreign Office issued Dahl a visa and diplomatic identification card and handed him his travel orders. Three days later, per his instructions, he took a train to Glasgow, where he boarded a Polish ship bound for Canada. During the uneventful two-week crossing, he contemplated his new government appointment with a heavy heart. He passed the time trading war stories with a fellow passenger, a RAF pilot by the name of Douglas Bisgood who was, worse luck, being sent to an officer training camp on the east coast of Canada. After being told he could no longer fly combat missions, Dahl had declined the RAF's offer to become an instructor and spend the rest of the war training new pilots. If the RAF training camps in Nairobi and Iraq were any indication, he would have been stuck in some abominable hellhole with nothing more than a strip of hangars and Nissan huts to remind him of civilization. Despite his reservations about his upcoming desk duty, he did not envy Bisgood one bit.

By the time Dahl made his way to Washington and assumed his duties at the British Embassy in late April, he found the capital already in the full bloom of spring and exuding an almost devil-may-care optimism. The restaurants, stores, and theaters were flourishing, and the streets were crowded with happy throngs enjoying all the comforts and amenities of modern urban life. Everyone in America looked prosperous, well dressed, and almost indecently healthy. The bullish mood in Washington, so different from downtrodden London, seemed to stem from the American certainty that they would win the day. There was historical precedent for such confidence -- the United States had never lost a war. Thanks to the strength of their armed forces, industry, and abundant resources, the Americans were convinced that victory was a question not of "if" but of "how long." A war was raging, but most people he met seemed chiefly concerned with gas rationing, the availability of summer suits, and the rumored shortage of cigarettes.

Everywhere he went, people wanted to talk to him about Winston Churchill, whose Christmas visit, just weeks after Pearl Harbor, had aroused great interest. It had been the prime minister's first meeting with President Roosevelt since their dramatic rendezvous at sea in August 1941, when Churchill had hoped to come away with a declaration of war and instead had to settle for the disappointing eight-point joint declaration of peace aims known as the Atlantic Charter. Since then the Japanese attack had destroyed much of the U.S. Navy and demonstrated that even the wide Pacific could not keep the enemy from America's shores. The Japanese had dealt England a terrible blow as well: on December 10 they had sunk two of Britain's largest warships, the Prince of Wales and Repulse. Almost immediately after declaring war on the Japanese, Churchill had crossed the Atlantic to show his solidarity with Roosevelt and the United States. But he had also come, pink-faced and bow-tied, full of fighting spirit and rolling cadences, to marshal the country's immense strength on behalf of the Allied coalition in what was now a global war.

Churchill's yuletide call on the White House had been a well-publicized goodwill tour with a deadly serious purpose -- to convince Roosevelt it was time for the machinery of combined action to slip into high gear. Military secrecy, of course, dictated that the details of their conversations be withheld, but one White House communiqué had emphasized that the "primary objective" of the talks was "the defeat of Hitlerism throughout the world." The Germans and Italians, now with the help of the Vichy French, were mounting dire new assaults on British forces. In the first few months of 1942, Japan had handed them one disastrous defeat after another in the Far East -- Hong Kong and Singapore were lost, and public confidence in Churchill had been severely shaken. Both leaders were in agreement that the Allied coalition had to act with greater coordination in the struggle against the Axis powers, and the call for greater "synchronization" had filled the newspapers in London and Washington.

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.