Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

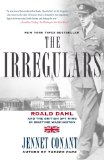

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

Despite all the hoopla about their historic alliance, Dahl knew from what he had read and heard to expect a certain amount of ambivalence, if not residual anti-British sentiment. It would be nothing compared to the entrenched isolationism that had characterized America during the so-called Phony War -- as a skeptical senator had dubbed the stalemate between September 1939 and April 1940, when Hitler but did not attack for nine months -- reflecting the opinion of the majority of U.S. citizens who were not yet disposed to see Hitler as a threat to democracy or to the American way of life. The American public was so determined to stay neutral that they pressured Roosevelt to remain aloof from the European conflict and vigilantly protested any assistance to the Allies as a sign that he was giving into Britain's blatant war propaganda. Political feeling was so overwhelmingly isolationist that only after France fell, and England was under siege and enduring her "darkest hour," was Roosevelt able to offer military aid to England under the guise of the Lend-Lease Act -- and even then with the argument that it was vital to the defense of the hemisphere. After Pearl Harbor, America's dramatic entry into the war had brought with it a great burst of support for England, but it had faded all too quickly. Inevitably, as the weeks became months and the fighting ground on, the old doubts had returned. Some of the current bad feeling was the frustration produced by a battle without early victories, and the usual tendency in such circumstances was to blame one's allies for not doing enough.

While public anxiety over the war had weakened their ranks, there were still a great number of hard-core noninterventionists, and they remained a powerful force whose influence stretched across the American political spectrum, including such diverse pro-Nazi types as the famed pilot Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne (who argued that fascism was the "wave of the future"), such notable senators as Burton Wheeler and Gerald Nye (who regarded the war as just the latest bloody chapter in Europe's long and savage history), and antiwar liberals like Charles Beard, Robert Hutchins, and Chester Bowles. This disparate crew, mostly Republicans and anti-New Dealers, had organized as the America First Committee, founded back in the fall of 1940, and still strove to return their country to the old, untrammeled path of private enterprise and national ends. They took the view that the whole continent of Europe should be written off as a total loss. While the public had little sympathy for the Germans, distrust of the plundering British Empire still ran deep. Only a year ago, a commonly expressed view in conservative American newspapers was "Let God Save the King." Now, instead of being chastened, they railed against Roosevelt for tricking the American people into going to war, and they accused England of already laying postwar plans for international plunder. While beloved by the British as their best hope, Roosevelt -- not to mention his wife, Eleanor, and little dog, Fala -- was reportedly regarded with utter loathing by a large segment of his own country.

Dahl's brief was vague, but he knew that the British Embassy in Washington functioned more or less as Whitehall's press office, with its main focus on maintaining close diplomatic relations with the Roosevelt administration and on monitoring the shifting loyalties of the fickle American people. He would be a small cog in the embassy's propaganda apparatus, working to manufacture the sort of positive information that could counter what was thought to be most damaging to Britain and encourage maximum cooperation in the prosecution of the war. He also knew that in the ongoing effort to drum up support for the war, the British Ministry of Information in London had organized a variety of publicity campaigns, a way of hand-feeding the press, radio, wire services, and other media that influenced American public opinion. Far and away the most effective of these campaigns had focused on the heroism of the Battle of Britain pilots, who had persevered despite horrendous losses to the Luftwaffe. Churchill's famous tribute to the valiant RAF eagles -- "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few" -- had become England's best sales pitch, urging the Americans to help "finish the job."

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.