Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

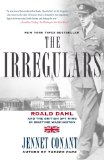

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

Dahl doubted he would be much good to his country in its public relations cause in the United States. Smart, acerbic, and impatient with ceremony, Dahl did not see himself as a natural diplomat. It was not just a question of his personal cynicism, though Churchill's rhetoric had not been much comfort when he and his fellow pilots were fighting for survival on Elevsis. There was no question in his mind that they should not have been there in the first place and had been "flung in at the deep end," totally unprepared, ill-equipped, and faced with impossible odds. It had been a colossal blunder. The enormity of the losses, the waste of life, still haunted him. Now, in his official capacity as assistant air attaché, he would be involved in the exchange of intelligence with the U.S. Army Air Force, and act as liaison between the two services -- but was expected to go gently, with nothing but broad smiles and approbation, as the Americans were the "new boys," and no one wanted to strain the burgeoning friendship between the two nations.

On his first day, he reported to the British Embassy, an impressive red-brick pile that was reportedly modeled after the work of Sir Christopher Wren and cost upward of $1 million to build in the late 1920s. It was every inch the traditional English country manor -- complete with an old chancery -- incongruously facing Massachusetts Avenue, with a grand drawing room with mirrored walls and marble pillars and the requisite green lawns, rose gardens, and swimming pool. Dahl was assigned a small office at the Air Mission, which was located in an annex. Until permanent housing could be arranged, he was put up at the Willard, an enormous grande dame of a hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, just two blocks from the White House, where he lived in comparative luxury after the deprivations back home. As soon as he was settled, he sent word to his mother -- he dutifully wrote home every other week throughout the war, laying aside time on Saturday afternoons -- and filled her in on his workplace, wonderful accommodations, and other banalities of his life in Washington. It was difficult to write without really saying anything, having been forewarned that he could not discuss his work and that embassy censors would scrutinize every piece of mail before including it in the diplomatic pouch to England. When his letters arrived at Grendon Underwood, they always bore the telltale label "Opened by the Examiner."

From the very beginning, his days were filled from morning to night with official luncheons, banquets, and receptions, as well as lectures and panels of all sorts. Boredom set in almost at once. Just as he had feared, it was "a most unimportant, ungodly job." The embassy was full of very serious, war-winning types who had never set foot anywhere near to the front. As the weeks passed, he became increasingly vexed and demoralized. In his former life, he had been admired for his ready wit, clever turn of phrase, and the ability to talk himself into and out of almost anything. Here in the United States he was becoming increasingly sullen and cranky. He did not even bother to hide his scorn for the endless round of parties that composed much of official life in Washington, and that, with America's entry into the war, had reached a level of frenzied conviviality.

His contempt for his glad-handing duties was compounded by what Churchill had referred to as "the inward excitement which comes from a prolonged balancing of terrible things." Dahl could not believe he had been cast as a cheerleader, trotted out as a handsome, battle-scarred champion of the British fighting spirit. How many times could he be expected to relive his experiences in North Africa for audiences of moist-eyed congressional wives? Or sing the praises of American airplanes' performance in flag-draped ballrooms? He was too fresh from the field to find sympathy with the War Office's use of the RAF's "intrepid flying men" as a propaganda tool. He felt humiliated at his predicament in Washington. "[I'd] just come from the war where people were killing each other," he recalled. "I'd been flying around, [seeing] all sorts of horrible things happening. And almost instantly, I found myself in the middle of a cocktail mob in America. On certain occasions, as an air attaché, I had to put on this ghastly gold braid and tassles. The result was I became rather outspoken and brash."

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.