Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

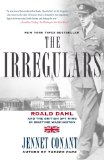

Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

If the Americans found him refreshing, his English superiors judged him tactless, and Dahl was not surprised to learn that less than a year into the job he had managed to land himself in hot water. Conceding that he might have been impudent on occasion, Dahl apologized for his behavior and promised to toe the line. While he had taken a singularly cavalier approach to his diplomatic duties thus far, he realized he rather liked America and was not in a hurry to be sent packing. With no meaningful defense work waiting for him back in England, and no promising career path to resume when the war was over, Dahl admitted to a friend that he found himself feeling oddly rudderless. His unlikely confidant was a self-made Texas oil tycoon and publishing magnate named Charles Edward Marsh, who had moved to the capital when the war made it the most interesting place to be.

Having already made his fortune, Marsh, like many men of means, wanted to contribute to the war effort and had decided to put himself at the disposal of the government. A dedicated New Dealer, he had come to town with the idea that he could put his big money and big personality to work for the Roosevelt administration, camping out alternately at the Mayflower Hotel and at the house of the construction magnate George Brown, before purchasing a stately four-story town house at 2136 R Street in Dupont Circle. He quickly turned the elegant nineteenth-century mansion into a well-financed Democratic political salon, where various cabinet members, senators, financiers, and important journalists could count on a good meal and stimulating conversation in the news-starved town. Over time prominent New Dealers came to regard Marsh's white sandstone mansion, with its Palladian windows and Parisian-style wrought-iron grillwork, as their private clubhouse and used it as a cross between a think tank and a favorite watering hole. It had the added attraction of a side annex that was entered by a single inconspicuous door, which allowed important guests to come and go unseen. Among those who regularly passed through this discreet portal were Marsh's close friend Vice President Henry A. Wallace, Florida senator Claude Pepper, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, and Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones, who was one of the wealthiest and most influential of FDR's administrators, as well as most of the major columnists, including Drew Pearson, Walter Winchell, Walter Lippmann, and Ralph Ingersoll, editor of the crusading PM magazine, whose account of the Battle of Britain, Report on England, was a best seller. At one of these weekly gatherings, Pearson remembered Marsh introducing him to "a very vivacious, fast-talking young congressman" from Texas by the name of Lyndon B. Johnson, who the publisher had backed in his first campaign and promised was going places.

Dahl met Marsh at a party and immediately hit it off with the colorful millionaire, who was an exemplary host and an amusing and informative guide to Washington's stratified society, where new and old money, the congressional set and the diplomatic corps all jostled for recognition. As the months passed, Dahl formed the habit of dropping by Marsh's place after work for a drink, as it was just a block off Massachusetts Avenue at the foot of Embassy Row. More often than not he would linger, hoping for an invitation to dinner, as the company was good and the food far better than anything he could afford on his salary. "Charles was able to entertain on a grand level, and kept a very good staff and cook, so that during the war it was one of the best restaurants in town," recalled Creekmore Fath, a young Texas lawyer toiling in the Roosevelt administration who also frequented Marsh's table. "He entertained all sorts of Washington characters. You'd get a telephone call inviting you to dinner Wednesday, or a luncheon Friday at noon. Everybody came and traded information and gossip."

A Texan by choice rather than by birth, Marsh was a garrulous storyteller in the tradition of his adoptive state, and he and Dahl immediately fell into a good-natured rivalry that consisted mainly of trading sporting jabs about their respective homelands and telling dirty jokes at each other's expense. Passionate when it came to politics, Marsh loved an audience and would often hold forth into the wee hours on the progress of the war, the president's economic policies, the greatness of American industry, and what more he thought the United States could be doing on the home front to secure victory. At first Dahl regarded these lively, epithet-strewn monologues as fascinating tutorials, but over time he came to realize that it was more than just talk and that the opinions the publisher expounded at night in his paneled library showed up as the next morning's editorials in one of his daily papers.

Copyright © 2008 by Jennet Conant

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.