Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

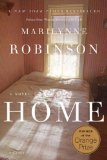

A Novel

by Marilynne Robinson

Each spring the agnostic neighbor sat his borrowed tractor with the straight back and high shoulders of a man ready to be challenged. Unsociable as he was, he called out heartily to passersby like a man with nothing to hide, intending, perhaps, to make the Reverend Boughton know, and know the town at large knew, too, that he was engaged in trespass. This is the very act against which Christians leveraged the fate of their own souls, since they were, if they listened to their own prayers, obliged to forgive those who trespassed against them.

Her father lived in a visible state of irritation until the crop was in, but he was willing to concede the point. He knew the neighbor was holding him up to public embarrassment year after year, seed time and harvest, not only to keep fresh the memory of his ill-considered opposition to the road, but also to be avenged in some small degree for the whole, in his agnostic view unbroken, history of religious hypocrisy.

Once, five of the six younger Boughtons - Jack was elsewhere - played a joyless and determined game of fox and geese in the tender crop of alfalfa, the beautiful alfalfa, so green it was almost blue, so succulent that a mist stood on its tiny leaves even in the middle of the day. They were not conscious of the craving for retaliation until Dan ran out into the field to retrieve a baseball, and Teddy ran after him, and Hope and Gracie and Glory after them. Somebody shouted fox and geese, and they all ran around to make the great circle, and then to make the diameters, breathless, the clover breaking so sweetly under their feet that they repented of the harm they were doing even as they persisted in it. They slid and fell in the vegetable mire and stained their knees and their hands, until the satisfactions of revenge were outweighed in their hearts by the knowledge that they were deeply in trouble. They played on until they were called to supper. When they trooped into the kitchen in a reek of child sweat and bruised alfalfa, their mother made a sharp sound in her throat and called, "Robert, look what we have here." The slight satisfaction in their father’s face confirmed what they dreaded, that he saw the opportunity to demonstrate Christian humility in such an unambiguous form that the neighbor could feel it only as rebuke.

He said, "Of course you will have to apologize." He looked almost stern, only a little amused, only a little gratified. "You had better get it over with," he said. As they knew, an apology freely offered would have much more effect than one that might seem coerced by the offended party, and since the neighbor was a short-tempered man, the balance of relative righteousness could easily tip against them. So the five of them walked by way of the roads to the other side of the block. Somewhere along the way Jack caught up and walked along with them, as if penance must always include him.

They knocked at the door of the small brown house and the wife opened it. She seemed happy enough to see them, and not at all surprised. She asked them in, mentioning with a kind of regret the smell of cooking cabbage. The house was sparsely furnished and crowded with books, magazines, and pamphlets, the arrangements having a provisional feeling though the couple had lived there for years. There were pictures pinned to the walls of bearded, unsmiling men and women with rumpled hair and rimless glasses.

Teddy said, "We’re here to apologize."

She nodded. "You trampled the field. I know that. He knows, too. I’ll tell him you have come." She spoke up the stairs, perhaps in a foreign language, listened for a minute to nothing audible, and came back to them. "To destroy is a great shame," she said.

"To destroy for no reason." Teddy said, "That is our field. I mean, my father does own it."

"Poor child!" she said. "You know no better than this, to speak of owning land when no use is made of it. Owning land just to keep it from others. That is all you learn from your father the priest! Mine, mine, mine! While he earns his money from the ignorance of the people!" She waved a slender arm and a small fist. "Telling his foolish lies again and again while everywhere the poor suffer!"

Excerpted from Home by Marilynne Robinson. Copyright © 2008 by Marilynne Robinson. Published in September 2008 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.