Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

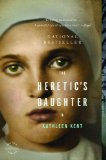

A Novel

by Kathleen Kent

WHEN I WOKE in the morning I was alone, my brothers risen, the objects scattered about the room looking gray and much used. I dressed quickly in the aching cold, my fingers as unbending as sausages. I crept down the stairs and heard the sound of Father's voice vibrating through the common room. The smell of cooking meat made my belly cramp but I crouched low on the stairs so I could see while not being seen, and listened. I heard him say ". . . it is a matter of conscience. And let us leave it at that."

Grandmother paused for a moment and, laying her hand on his shoulder, replied, "Thomas, I know of your differences with the parson. But this is not Billerica. It is Andover. And the Reverend Barnard will not brook absence from prayer. You must go today in good faith to the selectmen, before the Sabbath, and give your oath of fidelity to the town if you are to stay. Tomorrow, on the Sabbath, you must come with me to the meetinghouse for service. If you do not, you may be turned out. There is much conflict with newcomers laying claim to land. There are jealousies and resentments here enough to fill a well. If you stay long enough, you will see."

He looked into the fire, struggling to resolve the conflict within - between compliance to the laws of the meeting house and the desire to be left entirely to his own devices. I was very young but even I knew he was not greatly liked in Billerica. He was too solitary, too imposing in his unyielding beliefs in what was fair and what was not. And there was always whispered gossip of a past life, supposedly unlawful but never precisely named, that created a space for solitude. Last year Father had been fined 20 pence for arguing with a neighbor over property lines. His size, his great strength, and his reputation caused the neighbor to give way in the dispute, allowing Father to plant the boundary stakes where he wanted them despite the fine.

"Won't you do this for your wife and children?" she asked gently.

Bowing his head to his breakfast, he said, "For you and for my children I will do as you ask. As for my wife, you must ask her yourself. She has a great dislike for the Minister Barnard and coming from me it would be taken very badly."

FOR ALL GRANDMOTHER was soft and gentle, she was also persuasive, and like water wearing down rock she worked on Mother until she agreed to attend services on the morrow. Mother said under her breath, "I'd rather eat stones." But she brought out her good linen collar to be washed nonetheless. Richard and Andrew would leave with Father that very morning for the north end of Andover. They would put their mark on the town register and pledge faith to defend it from all attackers, promising to pay tithes in good time to its ministers. I pinched Andrew's arm hard and made him swear an oath that he would repeat everything he would see and hear. Tom and I were to be left behind with Mother for the cooking and gathering of firewood. Grandmother said that a respectful visit should also be made to the Reverend Francis Dane, who lived directly across from the meeting house. He had been pastor in North Andover for over forty years and was greatly loved. He was to have given way in his ministry years ago to the Reverend Barnard but, like a good shepherd, he sensed there was enough wolf in the younger man to warrant his continued protecting presence. The two men grudgingly shared the pulpit, and their sermonizing, every other week or so. I stood at the door and watched the cart's progress as far as the bend in the road, until they were swallowed behind mountainous drifts of snow.

When I closed the door Grandmother was already seated at her spinning wheel. Her foot was on the treadle but her eyes were thoughtfully on me. The spinner was beautifully carved of dark oak with leaves twining their way round and round the outer rim. It must have been very old, as the designs were too fanciful to have been made in the new England. She called to me and asked if I could spin. I told her yes, well enough, but that I could sew better, which was a statement only half true. A camp surgeon would have had a better hand with a cleaver to a limb than I with a needle on cloth. She spun the wool through knotted fingers glistening with sheep's oil and wrapped the threads neatly around the bobbin. Gently probing, she teased out the story of our days in Billerica just as she teased out the fine line of thread from the mix and jumble of the coarse wool in her hands.

Copyright © 2008 by Kathleen Kent

The third-rate mind is only happy when it is thinking with the majority. The second-rate mind is only happy when it...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.