Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

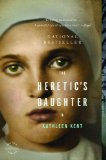

A Novel

by Kathleen Kent

I opened my eyes to the sound of Father's voice in the room. It was early morning, and though there was little light, I could see the drawn face of my mother in the gloom. They were speaking quietly but passionately and did not hear me pad on cold bare feet to stand next to my brother's cot. I looked at the blanket covering him and saw the faint movement of breath. I bent closer to peer at him and could plainly see on his face and neck the slightly raised pustules of the plague, rosy pink to deep purplish red; a pretty color on the petals of a rose or carnation. I took two, then three, steps backwards from his cot, and the thudding of my quickening pulse sounded like the drumming of hussars on horse back, sabers flashing through the air coming to sever our heads from our bodies. Many were the stories of entire families waking together in the morning but by supper all lying dead on the floor, festering in their seeping flesh. He coughed suddenly and I raised my shift in alarm over my face and turned away in fear. The shame over my disgust at his contagion was not enough to stay me as I raced with all the strength in my legs back up the stairs and into the safety of the garret.

ALTHOUGH IT WOULD cost us dearly, Grandmother insisted on sending to town for Andover's only physician. Richard went straightaway but it took him four hours to come back with the doctor, who stood a good distance from Andrew, careful not to touch anything in the room. Covering his face with a large handkerchief, he looked at Andrew for the space of three breaths, then made a rapid retreat through the front door. But not before being escorted out by my mother's voice, braying, "You're no better than a barber!" As he mounted his horse, he told Father that he would have to sound the alarm, post the Bill of Isolation for our family, and send the constable to read the bill to our neighbors. He said all this as he beat the ribs of his horse to ribbons making his escape. Grandmother did not let Richard back into the house but sent him away to stay for safekeeping with the Widow Johnson. As he had slept in the barn, there was a chance he would yet be free from contagion. He did not return that day, and we believed him to be in the home of at least one charitable Christian woman.

Grandmother, sitting at the common- room table, wrote a letter and called me over to her knee. She held my hands, saying, "Your father will be taking you and Hannah to your aunt Mary back in Billerica. You will stay there . . . perhaps for quite a while." I must have stirred, for she quickly said, "You will be happy there with your cousin Margaret. And you will have Hannah to look after." It had been years since I had seen my cousin, who lived in the northernmost part of Billerica, and my memory of her was of an odd, dark girl who would at times talk to an empty corner of a room.

"Can I take Tom as well?" I asked her, and my mother answered for her.

"No, Sarah. We need Tom to stay and help with the farm. Richard is gone and Andrew . . ." She paused, her meaning clear. Andrew would die soon or if he lived would be an invalid for months. It would be left to Tom and Father to carry all the weight of the fieldwork. Tom stood quietly by, regarding me with the eyes of someone falling down a hill made of powdered limestone. There came a hard knocking on the door, and a large, bristling man came in, announcing himself to be the constable. Holding the Bill of Isolation in one hand and a vinegar- soaked handkerchief in the other, he walked boldly to where Andrew lay groaning on his cot. His cratered face was as Andrew had described it and gave proof that some did survive the pox by the grace of God, or through protection by the Dev il. He read aloud the posting that would be nailed on the meetinghouse door for all to see so that we should not "spread the distemper through wicked carelessness." I looked about my grandmother's neat little room and saw no carelessness, only order and sober tranquillity. As he left our house he said under his breath, "God grant mercy . . ."

Copyright © 2008 by Kathleen Kent

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.