Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

"Of course," Connie began, shoving her anxiety aside. "The temptation is to begin a discussion of witchcraft in New England with the Salem panic of 1692, in which nineteen townspeople were executed by hanging. But the careful historian will recognize that panic as an anomaly, and will instead want to consider the relatively mainstream position of witchcraft in colonial society at the beginning of the seventeenth century." Connie watched the four faces nodding around the table, planning the structure of her answer according to their responses.

"Most cases of witchcraft occurred sporadically," she continued. "The average witch was a middle-aged woman who was isolated in the community, either economically or through lack of family, and so was lacking in social and political power. Interestingly, research into the kinds of maleficium," her tongue tangled on the Latin word, sending it out with one or two extra syllables, and she cursed inwardly for giving in to pretension, "which witches were usually accused of reveals how narrow the colonial world really was for average people. Whereas the modern person might assume that someone who could control nature, or stop time, or tell the future, would naturally use those powers for large scale, dramatic change, colonial witches were usually blamed for more mundane catastrophes, like making cows sick, or milk go sour, or for the loss of personal property. This microcosmic sphere of influence makes more sense in the context of early colonial religion, in which individuals were held to be completely powerless in the face of God's omnipotence." Connie paused for breath. She yearned to stretch, but restrained herself. Not yet.

"Further," she continued, "the Puritans held that nothing could reliably indicate whether or not one's soul was saved— doing good works wouldn't cut it. So negative occurrences, like a serious illness or economic reversal, were often interpreted as signs of God's disapproval. For most people, it was preferable to blame witchcraft, an explanation out of one's own control, and embodied in a woman on the margins of society, than to consider the possibility of one's own spiritual risk. In effect, witchcraft played an important role in the New England colonies— as both an explanation for things not yet elucidated by science, and as a scapegoat."

"And the Salem panic?" prodded Professor Silva.

"The Salem witch trials have been explained in numerous ways," Connie said. "Some historians have argued that the trials were caused by tension between competing religious populations in Salem, the more urban port city on the one hand and the rural farm region on the other. Some have pointed to longstanding envy between family groups, with particular attention paid to the monetary demands made by an unpopular minister, Reverend Samuel Parris. And some historians have even claimed that the possessed girls were hallucinating after having eaten moldy bread, which can cause effects similar to LSD. But I see it as the last gasp of Calvinist religiosity. By the early eighteenth century, Salem had moved from being a predominantly religious community to being more diverse, more dependent on shipbuilding, fishing, and trade. The Protestant zealots who had originally settled the region were being supplanted by recent immigrants from England, who were more interested in the business opportunities in the new colonies than in religion. I think that the trials were a symptom of this dynamic shift. They were also the last major outbreak of witchcraft hysteria in all of North America. In effect, the Salem panic signaled the end of an era that had had its roots in the Middle Ages."

"A very insightful analysis," commented Professor Chilton, still in his bemused, bantering tone. "But haven't you overlooked one other significant interpretation?"

Connie smiled at him, the nervous grimace of an animal fending off an attacker. "I am not sure, Professor Chilton," she answered. He was toying with her now. Connie silently begged for time to accelerate past Chilton's teasing, to catapult her instantly to Abner's Pub, where Liz and Thomas would be waiting, and where she could finally stop talking for the day. When she was tired, Connie's words sometimes ran together, tumbling out in an order not fully under her control. As she watched Chilton's crafty smile she worried that she was reaching that level of fatigue. Her stupid blunder over maleficium was a hint. If only he would just let her pass….

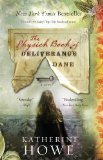

From The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane by Katherine Howe. Copyright 2009 Katherine Howe. To be published in June 2009. Available wherever books are sold. All rights reserved.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.