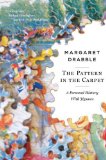

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Personal History with Jigsaws

by Margaret DrabbleForeword

This book is not a memoir, although parts of it may look like

a memoir. Nor is it a history of the jigsaw puzzle, although

that is what it was once meant to be. It is a hybrid. I have always

been more interested in content than in form, and I have never

been a tidy writer. My short stories would sprawl into novels, and

one of my novels spread into a trilogy. This book started off as a

small history of the jigsaw, but it has spiralled off in other directions,

and now I am not sure what it is.

I first thought of writing about jigsaws in the autumn of ????,

when my young friend Danny Hahn asked me to nominate an

icon for a website. This government-sponsored project was collecting

English icons to compose a ‘Portrait of England’, at a time

when Englishness was the subject of much discussion. At random

I chose the jigsaw, and if you click on ‘Drabble’ and ‘jigsaw’ and

‘icon’ you can find what I said. I knew little about jigsaws at this

point, but soon discovered that they were indeed an English invention

as well as a peculiarly English pastime. I then conceived the

idea of writing a longer article on the subject, perhaps even a short

book. This, I thought, would keep me busy for a while.

I had recently finished a novel, which I intended to be my last,

in which I believed myself to have achieved a state of calm and

equilibrium. I was pleased with The Sea Lady and at peace with the

world. It had been well understood by those whose judgement I

most value, and I had said what I wanted to say. I liked the idea of

writing something that would take me away from fiction into a

primary world of facts and pictures, and I envisaged a brightly

coloured illustrated book, glinting temptingly from the shelves of

gallery and museum shops amongst the greetings cards, mugs and

calendars portraying images from Van Gogh and Monet. It would

make a pleasing Christmas present, packed with gems of esoteric

information that I would gather, magpie-like, from libraries and

toy museums and conversations with strangers. I would become

a jigsaw expert. It would fill my time pleasantly, inoffensively. I

didn’t think anyone had done it before. I would write a harmless

little book that, unlike two of my later novels, would not upset or

annoy anybody.

It didn’t work out like that.

Not long after I conceived of this project, my husband Michael

Holroyd was diagnosed with an advanced form of cancer and we

entered a regime of radiotherapy and chemotherapy all too familiar

to many of our age. He endured two major operations of

hitherto unimagined horror, and our way of life changed. He dealt

with this with his usual appearance of detachment and stoicism,

but as the months went by I felt myself sinking deep into the paranoia

and depression from which I thought I had at last, with the

help of the sea lady, emerged. I was at the mercy of ill thoughts.

Some of my usual resources for outwitting them, such as taking

long solitary walks in the country, were not easily available. I

couldn’t concentrate much on reading, and television bored me,

though DVDs, rented from a film club recommended by my sister

Helen, were a help. We were more or less housebound, as we were

told to avoid public places because Michael’s immune system was

weak, and I was afraid of poisoning him, for he was restricted to an

unlikely diet consisting largely of white fish, white bread and

mashed potato. I have always been a nervous cook, unduly conscious

of dietary prohibitions and the plain dislikes of others, and the

responsibility of providing food for someone in such a delicate

state was a torment.

The jigsaw project came to my rescue. I bought myself a black

lacquer table for my study, where I could pass a painless hour or

two, assembling little pieces of cardboard into a preordained

pattern, and thus regain an illusion of control. But as I sat there, in

the large, dark, high-ceilinged London room, in the pool of lamplight,

I found my thoughts returning to the evenings I used to

spend with my aunt when I was a child. Then I started to think of

her old age, and the jigsaws we did together when she was in her

eighties. Conscious of my own ageing, I began to wonder whether

I might weave these memories into a book, as I explored the

nature of childhood.

Excerpted from The Pattern in the Carpet by Margaret Drabble. Copyright © 2009 by Margaret Drabble. Excerpted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are either well written or badly written. That is all.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.