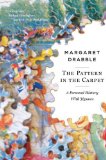

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Personal History with Jigsaws

by Margaret Drabble

This was dangerous terrain, and I should have been more wary

about entering it, but my resistance was low. I told myself that there

was nothing dangerous in my relationship with my aunt, and that

my thoughts about her could offend nobody, but this was stupid of

me. Any small thing may cause offence. My sister Susan, more

widely known as the writer A. S. Byatt, said in an interview somewhere

that she was distressed when she found that I had written

(many decades ago) about a particular teaset that our family

possessed, because she had always wanted to use it herself. She felt

I had appropriated something that was not mine. And if a teapot

may offend, so may an aunt or a jigsaw. Writers are territorial, and

they resent intruders.

I fictionalized my family background in a novel titled The

Peppered Moth, which is in part about genetic inheritance. I scrupulously

excluded any mention of my two sisters and my brother, and

I suspect that, wisely, none of them read it, but I was made

conscious of having trespassed. This made me very unhappy. I

vowed then that I would not write about family matters again (a

constraint which, for a writer of my age, constitutes a considerable

loss) but as I sat at my dark table I began to think I could legitimately

embark on a more limited project that would include

memories of my aunt’s house. These are on the whole happy

memories, much happier than the material that became The

Peppered Moth. I wanted to rescue them. Thinking about them

cheered me up and recovered time past.

But my new plan posed difficulties. I could not truthfully

present myself as an only child (as some writers of memoirs have

misleadingly done) and I have had to fall back on a communal

childhood ‘we’, which in the following text usually refers to my

older sister Susan and my younger sister Helen. My brother

Richard is considerably younger than me, and his childhood

memories of my aunt are of a later period, although he did spend

many holidays with her.

This book became my occupational therapy, and helped to pass

the anxious months. I enjoyed reading about card games, board

games and children’s books, and all the ways in which human

beings have ingeniously staved off boredom and death and despised

one another for doing so. I enjoyed thinking about the nature of

childhood and the history of education and play. For an hour or

two a day, making a small discovery or an unexpected connection,

I could escape from myself into a better place.

I don’t mean in these pages to claim a special relationship with

my aunt. My father once said to me, teasingly, ‘Are you such a

dutiful niece and daughter because you married into a Jewish family?’

And I think that the Swifts may have played a part in my

relationship with Auntie Phyl. I was captivated by the family of

my first husband, Clive Swift. He was the first member of his

generation to marry out, but despite this I was made welcome. I

loved the Swifts’ strong sense of mutual support and their demonstrative,

affectionate generosity. They were a powerful antidote to

the predominantly dour and depressive Yorkshire Drabbles and

Staffordshire Bloors. It was a happy day that introduced me to

Clive and the Swifts.

In The Peppered Moth I wrote brutally about my mother’s

depression, and I never wish to enter that terrain again. It is too

near, too ready to engulf me as it engulfed her. Some readers have

written to me, taking me to task for being hard on my mother,

but more have written to thank me for expressing their complex

feelings about their own mothers. I had hoped that writing about

her would make me feel better about her. But it didn’t. It made me

feel worse.

Both my parents were depressive, though they dealt with this in

different ways. My father took to gardening and walking with his

dog, my mother to Radio 4 and long laments. He was largely

silent, though Helen reminds me that he used to hum a lot. My

mother could not stop talking. Her telephone calls, during which

she complained about him bitterly for hour after hour, seemed

never-ending. The last decades of their marriage were not happy,

but when they were on speaking terms they would do the Times

crossword together.

Excerpted from The Pattern in the Carpet by Margaret Drabble. Copyright © 2009 by Margaret Drabble. Excerpted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.