Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Prologue

Men in my family always left their place of birth. When my father was seventeen years old he bought passage on a boat to Yaffo. It was a two-way ticket. The British, who ruled Palestine then, would never have let him enter without it. He did not have an immigration certificate.

I am told he was a quiet, slim youth, strangely intense, and fierce when aroused. My grandfather once had to buy off the Head of Police after my father had beaten up the son of a rich barrel-merchant. The young goy taunted my father and called him a dirty Jew. The taunter was big and fat, and smoked cigarettes. My father, who was half the goy’s size, almost killed him with a stick he had grabbed from a lame old charwoman. It took three policemen to tear my father off his victim.

Aunt Rina, who was eight then, claims no one could pry the stick from my father's hand. Finally the Chief of Police broke my father's thumb with a hammer. They put my father in jail, where he stayed for four days. He was fifteen at the time.

Aunt Rina, who now lives in Toronto, was hopelessly in love with him then. Half the town beauties were. Even now at the age of sixty seven, when she speaks of him her eyes light up and her husband Yitz'chak looks aside or busies himself with a book.

When I asked my father why his thumb was crooked, he said it had bent when he sucked on it, as a baby. My father had beautiful hands and the crooked thumb was glaringly noticeable. Only when I was old enough to talk to my uncle Mordechai as an equal did I learn the true story.

It had cost my grandfather two thousand zlotti, a fortune, to get my father out of jail. When my father finally came home he was sick for a month. Wild stories circulated. He had been beaten up. Two of his front teeth were missing. Some said he was raped by the guards, who had been bribed by the rich merchant. These were old Cossacks who remained from the days of the Russian occupation. They were short and thickset and their sexual appetites were legendary.

My father kept to his bed for two weeks. He did not notice anybody. All the time he was in bed he was sharpening a long knife he had made.

My grandfather was in the leather trade, and there were many knives around the house: small knives for trimming fine leather used in ladies' slippers, flat knives for splitting raw leather, and sharp, long blades for cutting through tough hide. My father made a new knife from a saw blade and sharpened it endlessly-- no one could make him stop. My grandmother cried and begged him, but he paid her no heed. When she brought him chicken broth, he would sit up in bed, hide the knife under his thigh, and eat. Then he would pull it from under the covers and start all over again.

My grandfather was a tall, husky Jew. He had a thick black beard and testy blue eyes. His one passion was the cards. The only one who could beat him at a card game was my father. When my father lay in bed recuperating, they played cards every night, and talked. My father would not surrender his knife. Each morning when the Shiksa maid peeked through the keyhole she saw him spitting on the black whetstone, and soon the srik-srak, srik-srak sound recommenced.

It was autumn and just before the high holidays. The atmosphere in town grew tense; there was talk of a pogrom. The Cossacks at the town jail muttered among themselves. All the Jews were nervous.

On the eve of Yom Kippur the Rabbi, Rebb Itzelle Tuvim, came to the house. Aunt Rina says his face radiated light. To hear her tell it, he was walking on an inch of air. He came in, washed his hands at my grandfather's porcelain basin, and ate a piece of Challah. Then he went into my father's room and closed the door behind him.

This was just before the Large Supper, the last meal before the fast, and the yard was teeming with beggars and the needy. The day before, my grandfather had sold a hundred pairs of felt boots to the Hetman of Cossacks, and in celebration my grandmother cooked Tchulent for all the town's poor Jews, to fortify them for Kol Nidrey, the Yom Kippur eve prayer that annuls all vows.

Excerpted from The Debba by Avner Mandelman. Copyright © 2010 by Avner Mandelman. Excerpted by permission of Other Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Ordinary Love

by Marie Rutkoski

A riveting story of class, ambition, and bisexuality—one woman risks everything for a second chance at first love.

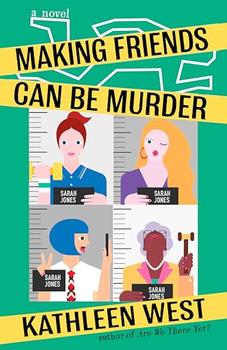

Making Friends Can Be Murder

by Kathleen West

Thirty-year-old Sarah Jones is drawn into a neighborhood murder mystery after befriending a deceptive con artist.

Children are not the people of tomorrow, but people today.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.