Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

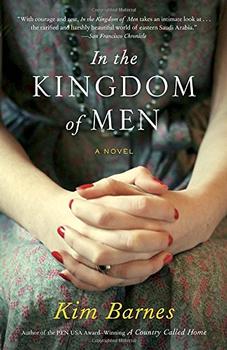

A Novel

by Kim Barnes

And then, that summer I turned seven, the cancer came up through my mother's bones like it had been biding its time, took what smile was left, took her teeth and blanched her skin to parchment. I would lie in our bed and cradle my dolly in a tea towel while my mother wept and prayed that God would take her and my grandmother offered another spoonful of laudanum. When, finally, God answered my mother's prayers, and then, only a few months later, my grandmother was felled by a blood clot that the doctor said had bubbled up from her broken heart, I was ordered into my grandfather's custody.

He came to the city orphanage in his old Ford pickup, and I watched from the doorway as he approached, a lean man, sinewy and straight, with a strong way of moving forward, like he was forcing his way through water. Pinched felt hat, starched white shirt, black tie and trousers - only the seams of his brogans, caked with mud, gave him away for the scabland farmer he was when not in the pulpit.

My nurse had dressed me in a modest blouse and jumper, but I refused the hard shoes she offered and wore instead my mother's old riding boots, an extra sock stuffed in each toe. The first thing my grandfather did was have me open my suitcase. My doll, my mother's rhinestone tiara, her wedding ring - all worldly, my grandfather said, the devil's tricks and trinkets, and he left them with the orphanage to pawn.

I wailed all the way to Shawnee, but my grandfather didn't speak a word. By the time we took the road south that led to the flat edge of town - that marginal land where the poorest whites and poorer blacks scraped out a living - I had cried myself into a snubbing stupor. He held my door, waited patiently as I climbed down and stood facing the narrow two-room shack with its broken foundation and sagging roof, the outhouse in back a haphazard construction of split pine. I trailed him through the kitchen, its walls papered with newsprint, pasted with flour and water, stained dark with soot, and into the bedroom, where he placed my suitcase on the horsehair mattress. He peered down at me, laid his hand on top of my head. "God will keep us," he said, pulled the door shut, and left me alone.

From the room's single window, I saw that he had changed into his patched work clothes, and I watched as he hitched the jenny mule, threw the reins over his shoulders, and returned to the plot he'd been plowing. What I found in that house was little: tenpenny nails in the wall, hung with my grandfather's good hat and suit; a two-door cupboard that held Karo, flour, sugar, a salted ham hock; an oilcloth-covered table and two weak chairs; a short-wicked kerosene lantern; a potbellied stove streaked with creosote; the cot that my grandfather had set in the kitchen and covered with an old wool blanket so that I might have the bed. I moved to the porch, found the washbasin, the straight razor, the leather strop, and a cropped piece of flannel that he used for a towel. I sat on the single-plank step and watched him chuck the mule up one row and down another until he put the plow away, came and stood in front of me, wiping the sweat from his brow.

"Where's my dinner, sister?" he asked gently. I hadn't thought to feed him, didn't know how. He led me back to the cupboard, showed me the cast-iron skillet, the knife, how to make red-eye gravy with the ham drippings, flour, and salt. Over the next week, we would eat that ham right down to the bone, boil it for soup on Saturday, crack it for marrow. I learned what it meant to be hungry, learned that Sundays meant more food and a healthy helping of God's word.

Because he now had a child to care for, my grandfather left the circuit, and he counted it as God's goodwill that a small congregation east of the city was in need of a pastor. The parishioners, some white, most black, folded us in, and though I had no siblings, they called me Sister Gin. I wasn't yet old enough to understand what the townspeople might think - that poor little white girl - and spent the Sabbath wedged in a hard oak pew between skin that ran from pale pink to sallow, dusky to dark. My grandfather's dictates were absolute, but in his eyes, all of God's children, red and yellow, black and white, were bound by the same mortal sin, given the same chance at redemption. I sat in fascinated horror, the sanctified moaning around me, as I listened to my grandfather's hellfire sermons that foretold the woe of every unsaved soul. Blood to the horse's bridle, flames licking the flesh - the punishment that would come my way if I didn't repent, but no matter how hard I considered my deeds, I didn't yet know what sins to confess.

Excerpted from In the Kingdom of Men by Kim Barnes. Copyright © 2012 by Kim Barnes. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are either well written or badly written. That is all.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.