Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

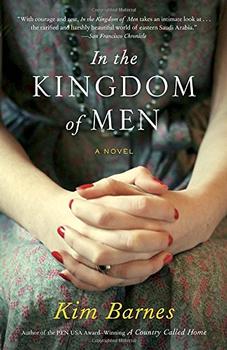

A Novel

by Kim Barnes

Who knows what gives rise to our sensibilities? Maybe it was some seed of resistance sown in me by my grandmother that allowed me to keep my soul to myself. Maybe it was just the way I was - turned funny, I heard them say. They didn't even bother to hide their mouths. No matter the color of my skin, I was the kind of girl they watched from the corners of their eyes, the kind of girl that brought them to predictions - headed to ruin if I didn't get my head straight, my heart right with God. I wasn't like them, wasn't like anybody I knew.

It was the characters in books who spoke to me, reflected some secret part of myself. When the librarian handed me To Kill a Mockingbird, I read it straight through, then hid it beneath my bed. "I lost it," I told the librarian. "I'll work check-in and checkout during recess to pay." She was satisfied, and so was I. It was a sin that I was jealous of and wanted to keep - the worst sin of all.

Walking home from school one afternoon, the September air thick with gray aphids, Anne of Green Gables open in my hands, I found a girl asleep on her sack, cotton tufting her hair. Fall harvest meant more hours in the field for the black children of South Town, the season's sun beating down, the long, long sack trailing behind like an earthbound anchor. Maybe that was when I began to understand that, no matter how different I was, my life would never be as hard as hers. I sat at the edge of the patch and watched her for a long time, then tore away one page of the book and then another, planting them in the soil beneath her bare feet as though they might sprout like Jack's magic beanstalk and carry her aloft, as though I were feeding the girl her dreams.

When the librarian discovered the ruined book, she said that two was too many and sent me home with a bill. That was the first time I lied outright to my grandfather. Ignoring any lessons I might have learned about false accusation, I described in detail how Tug Larson, the schoolyard bully, had knocked the novel from my hands. "He grabbed me," I said, "and pushed me down." I cried and showed my grandfather the bruises I had pinched on my arms to convince him how wounded I was. He grew solemn, said he would talk with the boy, but I insisted it would only make things worse, that he was already being given detention, and shouldn't I forgive? My grandfather was placated, and I felt a surge of relief and tingling possibility. I had transgressed, might confess and be forgiven, but I had discovered something that intrigued me even more: I could lie and not be struck dead in my shoes.

I remembered my grandmother's ways, used the last of our flour and lard to bake half a batch of sugar cookies, told my grandfather I was taking them to Sister Woody, an elderly parishioner who lived down the road, and he nodded his approval at my charity. I felt like skipping as I made my way out the door. I had no destination, only a desire to be free. I walked an easy two miles, ate half the cookies, fed the rest to the crows, turned around, and came home happy with the news that Sister Woody's health was improving.

I became braver, told bigger lies, and walked the farmland for hours or hid with my book in the neighbor's barn. In gym class, I let my body have its joy, leaping and sprinting ahead of my classmates. When my teacher suggested I try out for girls' basketball, I forged a careful note home that said I was helping clean the blackboards after school. I made the team and for the first time felt part of something, like I might be someone's friend, running up and down the court and hollering back and forth like it was a normal thing for a girl to do. I skipped the communal showers, unable to imagine letting myself be seen naked, left my knee-length trunks and sleeveless top in my locker, and ran as fast as I could, hoping to beat my grandfather home. He would sit down to the dinner I made him and never say a word about my wild hair, my ruddy skin, and I believed I had fooled him until the evening he rode into town on the mule and appeared at practice still in his farm clothes, pulled out the worn Bible, and filled the gymnasium with his voice. "The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman's garment: for all that do so are an abomination unto the Lord thy God!" He clapped the good book closed, pointed me to the door, and I slunk out, shamed not by my sin but by the looks of pity on the faces of my teammates. Once home, he sent me to my room and sat at the foot of my bed, studying me with intense sadness, as though he might see the workings of my deceitful soul. "I can't let you burn in hell," he said, and raised the leather strop. The fierceness of his whipping came up through my bones, rattled like dry seeds in my ears. After, he held me and cried. Maybe that's why I can forgive him. He only meant to save me.

Excerpted from In the Kingdom of Men by Kim Barnes. Copyright © 2012 by Kim Barnes. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The good writer, the great writer, has what I have called the three S's: The power to see, to sense, and to say. ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.