Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

While I was at the Frankfurt Book Fair a week later, just before heading off to co-host a table full of publishing pals for dinner, my mother called to tell me that she almost certainly had cancer. The hepatitis wasn't viral; it was related to a tumor in her bile duct. It would be good news if the cancer was only there, but it was far more likely that it had started in the pancreas and spread to the bile duct, which would not be good news at all. There were also spots on her liver. But I was not to worry, she said, and I was certainly not to cut my trip short and come home.

I can't remember much of what I said, or what she replied. But she soon changed the subject - she wanted to talk to me about my job. I'd recently told her that I'd become weary of my work, for all the same boring reasons privileged people get sick of their white-collar jobs: too many meetings, too much email, and too much paperwork. Mom told me to quit. "Just give two weeks' notice, walk out the door, and figure out later what to do. If you're lucky enough to be able to quit, then you should. Most people aren't that fortunate." This wasn't a new perspective that came from the cancer - it was vintage Mom. As much as she was devoted to intricate planning in daily life, she understood the importance of occasionally following an impulse when it came to big decisions. (But she also recognized that not everyone was dealt the same cards. It's much easier to follow your bliss when you have enough money to pay the rent.)

After we hung up, I didn't know if I would be able to make it through the dinner. The restaurant was about a mile from my hotel. I walked to clear my head, but my head didn't clear. I confided the news about Mom's cancer to my co-host, a good friend, but to no one else. I had a feeling of dizziness, almost giddiness. Who was this person drinking beers and eating schnitzel and laughing? I didn't allow myself to think about Mom - what she was feeling; whether she was scared, sad, angry. I remember her telling me on that call that she was a fighter and that she was going to fight the cancer. And I remember telling her I knew that. I don't think I told her I loved her then. I think I thought it would sound too dramatic - as though I were saying goodbye.

When I got back to my hotel after dinner, I looked around the room and then out the window. The river Main was barely visible under the city streetlights; it was a rainy night, so the roadway glistened in such a way that the lines between the river, the sidewalk, and the street were obscured. The hotel housekeeping staff had folded my big, fluffy white duvet into a neat rectangle. Beside my bed was a stack of books and some hotel magazines. But this was one of the nights when the printed word failed me. I was too drunk, too confused, too disoriented - by the hour of night, and also by the knowledge that my family's life was changing now, forever - to read. So I did the hotel room thing. I turned on the TV and channel-surfed: from the glossy hotel channel to the bill channel (had my minibar item from the night before really cost that much?) to Eurosport and various German channels, before settling on CNN and the familiar faces and voices of Christiane Amanpour and Larry King.

When Mom and I later talked about that night, she was surprised at one part of my story: that I had watched TV instead of reading. Throughout her life, whenever Mom was sad or confused or disoriented, she could never concentrate on television, she said, but always sought refuge in a book. Books focused her mind, calmed her, took her outside of herself; television jangled her nerves.

There's a W. H. Auden poem called "Musée des Beaux Arts," written in December 1938, just after Kristallnacht. In it is a description of a painting by Brueghel, in which the old master depicts Icarus falling from the sky while everyone else, involved in other things or simply not wanting to know,"turns away / quite leisurely from the disaster" and goes about daily tasks. I thought about that poem a lot over the next few days of the fair as I chatted about books, kept my appointments, and ate frankfurters off cardboard-thin crackers. The poem begins, "About suffering they were never wrong, / The Old Masters: how well they understood / Its human position; how it takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along." While at the fair, I felt the "someone else" was me. Mom was suffering; I was going on with my life.

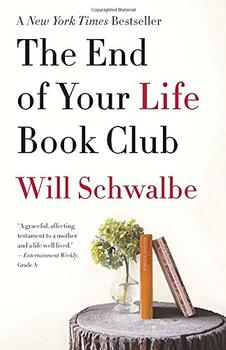

Excerpted from The End of Your Life Book Club by Will Schwalbe. Copyright © 2012 by Will Schwalbe. Excerpted by permission of Knopf. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.