Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Peering over his spectacles, Abdullah began recounting my life to

the audience, braiding sentences in English into his speech, ignoring

the sign in the courtroom dictating the use of the Malay language

in court.

"Judge Teoh was only the second woman to be appointed to the

Supreme Court," he said. "She has served on this Bench for the past

fourteen years . . ."

Through the high, dusty windows I saw the corner of the cricket

field across the road and, further away, the Selangor Club, its mock-

Tudor facade reminding me of the bungalows in Cameron Highlands.

The clock in the tower above the central portico chimed, its

languid pulse beating through the walls of the courtroom. I turned

my wrist slightly and checked the time: eleven minutes past three;

the clock was, as ever, reliably out, its punctuality stolen by lightning

years ago.

". . . few of us here today are aware that she was a prisoner in a

Japanese internment camp when she was nineteen," said Abdullah.

The advocates murmured among themselves, observing me with

heightened interest. I had never spoken of the three years I had spent

in the camp to anyone. I tried not to think about it as I went about

my days, and mostly I succeeded. But occasionally the memories

still found their way in, through a sound I heard, a word someone

uttered, or a smell I caught in the street.

"When the war ended," the chief justice continued, "Judge Teoh

worked as a research clerk in the War Crimes Tribunal while waiting

for admission to read law at Girton College, Cambridge. After

being called to the bar, she returned to Malaya in 1949 and worked

as a deputy public prosecutor for nearly two years . . ."

In the front row below me sat four elderly British advocates,

their suits and ties almost as old as they. Along with a number of

rubber planters and civil servants, they had chosen to stay on in

Malaya after its independence, thirty years ago. These aged Englishmen

had the forlorn air of pages torn from an old and forgotten

book.

The chief justice cleared his throat and I looked at him. "Judge

Teoh was not due to retire for another two years, so you will no

doubt imagine our surprise when, only two months ago, she told

us she intended to leave the Bench. Her written judgments are

known for their clarity and elegant turns of phrase . . ." His words

flowered, became more laudatory. I was far away in another time,

thinking of Aritomo and his garden in the mountains.

The speech ended. I brought my mind back to the courtroom,

hoping that no one had noticed the potholes in my attention; it

would not do to appear distracted at my own retirement ceremony.

I gave a short, simple address to the audience and then Abdullah

brought the ceremony to a close. I had invited a few well-wishers

from the Bar Council, my colleagues and the senior partners in

the city's larger law firms for a small reception in my chambers. A

reporter asked me a few questions and took photographs. After the

guests left, Azizah went around the room, gathering up the cups and

the paper plates of half-eaten food.

"Take those curry puffs with you," I said, "and that box of

cakes. Don't waste food."

"I know-lah. You always tell me that." She packed the food

away and said, "Is there anything else you need?"

"You can go home. I'll lock up." It was what I usually said to her

at the end of every court term. "And thank you, Azizah. For everything."

She shook the creases out of my black robe, hung it on the coat

stand and turned to look at me. "It wasn't easy working for you all

these years, Puan, but I'm glad I did." Tears gleamed in her eyes.

"The lawyers—you were difficult with them, but they've always

respected you. You listened to them."

"That's the duty of a judge, Azizah. To listen. So many judges

seem to forget that."

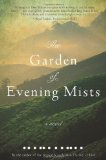

Excerpted from The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng. Copyright © 2012 by Tan Twan Eng. Excerpted by permission of Weinstein Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A book may be compared to your neighbor...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.