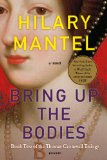

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Wolf Hall Trilogy #2

by Hilary Mantel

'I don't know, Cromwell,' old Sir John says. He takes his arm, genial. 'All these falcons named for dead women … don't they dishearten you?'

'I'm never disheartened, Sir John. The world is too good to me.'

'You should marry again, and have another family. Perhaps you will find a bride while you are with us. In the forest of Savernake there are many fresh young women.'

I still have Gregory, he says, looking back over his shoulder for his son; he is always somehow anxious about Gregory. 'Ah,' Seymour says, 'boys are very well, but a man needs daughters too, daughters are a consolation. Look at Jane. Such a good girl.'

He looks at Jane Seymour, as her father directs him. He knows her well from the court, as she was lady-in-waiting to Katherine, the former queen, and to Anne, the queen that is now; she is a plain young woman with a silvery pallor, a habit of silence, and a trick of looking at men as if they represent an unpleasant surprise. She is wearing pearls, and white brocade embroidered with stiff little sprigs of carnations. He recognises considerable expenditure; leave the pearls aside, you couldn't turn her out like that for much under thirty pounds. No wonder she moves with gingerly concern, like a child who's been told not to spill something on herself.

The king says, 'Jane, now we see you at home with your people, are you less shy?' He takes her mouse-paw in his vast hand. 'At court we never get a word from her.'

Jane is looking up at him, blushing from her neck to her hairline. 'Did you ever see such a blush?' Henry asks. 'Never unless with a little maid of twelve.'

'I cannot claim to be twelve,' Jane says.

At supper the king sits next to Lady Margery, his hostess. She was a beauty in her day, and by the king's exquisite attention you would think she was one still; she has had ten children, and six of them are living, and three are in this room. Edward Seymour, the heir, has a long head, a serious expression, a clean fierce profile: a handsome man. He is well-read if not scholarly, applies himself wisely to any office he is given; he has been to war, and while he is waiting to fight again he acquits himself well in the hunting field and tilt yard. The cardinal, in his day, marked him out as better than the usual run of Seymours; and he himself, Thomas Cromwell, has sounded him out and found him in every respect the king's man. Tom Seymour, Edward's younger brother, is noisy and boisterous and more of interest to women; when he comes into the room, virgins giggle, and young matrons dip their heads and examine him from under their lashes.

Old Sir John is a man of notorious family feeling. Two, three years back, the gossip at court was all of how he had tupped his son's wife, not once in the heat of passion but repeatedly since she was a bride. The queen and her confidantes had spread the story about the court. 'We've worked it out at 120 times,' Anne had sniggered. 'Well, Thomas Cromwell has, and he's quick with figures. We suppose they abstained on a Sunday for shame's sake, and eased off in Lent.' The traitor wife gave birth to two boys, and when her conduct came to light Edward said he would not have them for his heirs, as he could not be sure if they were his sons or his half-brothers. The adulteress was locked up in a convent, and soon obliged him by dying; now he has a new wife, who cultivates a forbidding manner and keeps a bodkin in her pocket in case her father-in-law gets too close.

But it is forgiven, it is forgiven. The flesh is frail. This royal visit seals the old fellow's pardon. John Seymour has 1,300 acres including his deer park, most of the rest under sheep and worth two shilling per acre per year, bringing him in a clear twenty-five per cent on what the same acreage would make under the plough. The sheep are little black-faced animals interbred with Welsh mountain stock, gristly mutton but good enough wool. When at their arrival, the king (he is in bucolic vein) says, 'Cromwell, what would that beast weigh?' he says, without picking it up, 'Thirty pounds, sir.' Francis Weston, a young courtier, says with a sneer, 'Master Cromwell used to be a shearsman. He wouldn't be wrong.'

Copyright © 2012 by Hilary Mantel

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading, you wish the author that wrote it was a ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.