Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Josephine

Lynnhurst, Virginia

1852

Mister hit Josephine with the palm of his hand across her left cheek and it was then she knew she would run. She heard the whistle of the blow, felt the sting of skin against skin, her head spun and she was looking back over her right shoulder, down to the fields where the few men Mister had left were working the tobacco. The leaves hung heavy and low on the stalk, ready for picking. She saw a man's bare back and the new hired man, Nathan, staring up at the house, leaning on a rake. The air tasted sweet, the honeysuckle crawling up the porch railings thick now with flower, and the sweetness mixed with the blood in her mouth.

The blow came without warning, no reason that Josephine could say. She had been sweeping the front porch as she always did first thing, clearing off the dust and leaves blown up by the night wind. A snail had marked a trail across the dew-wet wood of the porch floor and rested its brown shell between the two porch rockers. Josephine had caught that snail with a sharp swoop of the broom, sent it flying out into the yard, and then she heard Mister's voice behind her, coming from inside the house. He said something she could not make out. It was not a question, there was no uplift in tone, nor was it said in anger. His voice was measured, it had seemed to Josephine then, before he hit her, not urgent, not hurried. She stopped her sweeping, turned around, looked to the house, and he walked out the wide front door, a proud front door Missus Lu always liked to say, and that's when his hand rose up. She saw his right arm bend, and his lips part just slightly, not to open but just the barest hint of dark space between them. And then his palm, the force of it against her cheek, and the broom dropping from her fingers, the clatter as it fell.

Something shifted in Josephine then, a gathering of disparate desires that before had been scattered. She could not name them all, there were so many, but most were simple things: to eat a meal when hunger struck her, to smile without thinking, to wear a dress that fit her well, to place upon the wall a picture she had made, to love a person of her choosing. These distilled now, perfectly, here on this September morning, her hunger for breakfast sharp in her belly, the sun pink and resplendent in the sky. Today was the last day, there would be no others.

Afterward, she tried but she could not explain it to Caleb, why this moment marked the course of things to come. The snail she remembered, the curve of its shell, and the hot colors of the dawn.

What came later—Dr. Vickers, what Missus Lu had done—did not change what Josephine decided then with Mister on the porch. Even if that day had held nothing more, she told Caleb, still she would have run. Yes, she would run.

As Josephine turned her head back around to face Mister, a warbler called from down toward the river, its sweet sweet sweet clear as the brightening day.

Mister said, "Look after your Missus. The doctor coming today, don't you forget."

He stepped off the porch, into the dirt of the front path and looked up at her, his dark beard dusty from the fields, his eyes shadowed. Last month the curing barn had burnt to the ground, and they'd lost some horses too, their screams terrible to hear. The winter before, Mister's father, Papa Bo, had passed on, and the cow stopped giving milk, and Hap the field hand died from a bee sting. He'd got all puffed up and started scrabbling at the ground, Otis said, like he was digging his own grave, save the others the work. Now Missus Lu and her fits. There was an affliction in Mister, he had cause for sorrow. But Josephine did not pity him.

She nodded, her cheek on fire.

Mister walked in long steps down the sloping back hill of the yard, across the raw furrowed rows they had had no seed to plant. Jackson, the Negro overseer, watched over the others. Picking time, and the field just barely begun. Over at the Stanmores' they had hundreds of acres, dozens of slaves, and already the first tobacco leaves were finished drying and sent to market, the wagons rumbling by the house, the nut-brown bundles piled high in the back. Mister would always spit when he saw one pass by on the road to town.

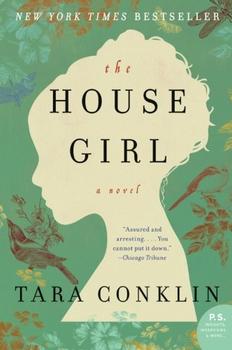

Excerpted from The House Girl by Tara Conklin. Copyright © 2013 by Tara Conklin. Excerpted by permission of William Morrow. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.