Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

From behind some of those doors came the muffled chorus of babies wailing. Azar listened carefully, as if, in their endless, hungry cries, there was a message for her, a message from the other side of time, from the other side of her body and flesh.

A nurse came to a halt in front of them. She was a portly woman with bright hazel eyes. She looked up and down at Azar and then turned to Sister.

"It's a busy day. We're trying to cope with the Eid-e-Ghorban rush, and I don't know if there's any room available. But come on up. We'll have the doctor at least take a look at her."

The nurse led them to a flight of stairs, which Azar climbed with difficulty. Every few steps, she had to stop to catch her breath. The nurse walked ahead, as if avoiding this prisoner with her baby and her agony, the perspiration glistening on her scrawny face.

They went from floor to floor, Azar hauling her body from one corridor to the next, one closed door to another. Finally, the doctor in one of the rooms motioned them in. Azar quickly lay down and submitted herself to the doctor's efficient, impersonal hands.

The baby inside her felt as tense as a knot.

"As I said before, we can't keep her here," the nurse said once the doctor was gone, the door swinging shut silently behind her. "She's not part of this prison. You have to take her somewhere else."

Sister signaled to Azar to get up. Descending stairs, flight after flight, floor after floor, Azar clasped the banister, tight, stiff, panting. The pain was changing gear. It gripped her back, then her stomach. She gasped, feeling as if the baby were being wrung out of her by giant hands. For a moment, her eyes welled up, to her biting shame. She gritted her teeth, swallowed hard. This was not a place for tears—not on these stairs, not in these long corridors.

Before leaving the hospital, Sister made sure the blindfold was tied hermetically over her prisoner's bloodshot eyes.

Back on the corrugated iron floor, the doors slammed shut. The van smelled of heat and violent suffering. As soon as the engine started, the chattering from the front picked up where it had left off. Sister sounded excited. There was a flirtatious edge to her voice and to her high-pitched laughter.

Back in position, Azar slouched slightly with fatigue. As the van zigzagged through the jarring traffic, she remembered the first time she took Ismael to her house. It had been a hot day, much like today. He smelled sweet, of soap and happiness, as he walked beside her down the narrow street. She wanted to show him where she came from, she had said, the house she lived in with its low brick walls, the blue fountain, and the jacaranda tree that dominated everything. He had been doubtful; what if her parents came back and caught him there? But he came anyway. Nothing but a quick tour, Azar promised, laughing, grabbing his hand. They ran from room to room, never letting go of that moment, of each other, of the perfume of the flowers that enfolded them.

She wondered where Ismael was, and if he was all right. It had been months since she'd had news of him, months when she did not even know if he was still alive. No, no, no. She shook her head repeatedly. She should not think about that. Not now. She had heard from some of the new prisoners that the men had also been transferred to the Evin prison. Most of the men. If they made it to Evin, it meant they had through the interrogations and everything else she did not dare think about at the Komiteh Moshtarak detention center. She was sure Ismael was one of those men. She was sure he in Evin with had to be.

Once again, the van came to a stop and the door swung open. This time, the blindfold did not come off. The sun shone feebly through it and into Azar's eyes as she faltered out of the van, tottering alongside Sister and Brothers into another building and then down a corridor. They must have entered the labor ward of another hospital, for soon the sounds of women moaning and screaming filled her ears. Azar felt a rush of hope. Maybe now they would leave her to the safe hands of the doctors. Maybe the agony would be over. The blindfold slid down a bit on one side, and from the opening, she watched eagerly the gray tiled floor of the long corridor and the metal feet of chairs along the walls. She felt the brisk passing of people, perhaps nurses, their soft shoes thudding down the hallway. Their bodies moving past raised a quick breeze to her face.

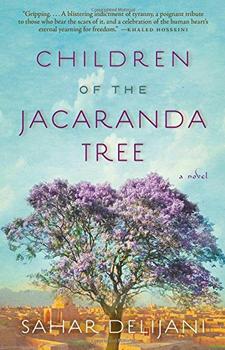

Excerpted from Children of the Jacaranda Tree by Sahar Delijani. Copyright © 2013 by Sahar Delijani. Excerpted by permission of Atria Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Any activity becomes creative when the doer cares about doing it right, or better.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.