Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Soon their course changed, and they were going up another flight of stairs. The sound of the women's moans drifted. Azar cocked her ears and knew they were taking her away from the labor ward. The corners of her eyes twitched. When they finally came to a stop and a door opened, she was led into a room and told to sit down. She lowered herself onto a hard wooden chair, exhausted. Sweat dripped from her forehead and into her eyes as a rush of pain came back to claim her. Soon the doctor will be here, she thought, trying to console herself.

Yet, she quickly realized it was not a doctor she was waiting for when, from behind the closed door, came the slip-slap of plastic slippers approaching; the noise grew louder and louder. She knew what that sound meant, and she knew when she heard it that she had to prepare herself. She gripped the warm, sweaty metal of the handcuff and squeezed her eyes shut, hoping the slip-slap would stride right past her door and leave her alone. When it fell silent behind the door, Azar's heart sank; they were here for her.

The door squeaked open. From underneath the blindfold, she had a glimpse of black pants and a man's skinny toes with long pointy nails. She heard him dawdle across the room, pull a chair raspingly over the floor, and sit down. Azar's body grew tense against the ominous being that she could not see but felt with every molecule of her body. The child inside her pushed and twisted. She winced, clasped into her chador.

"Your first and last name?"

In a quivering voice, Azar gave her name. She then said the name of the political party to which she belonged and the name of her husband. Another stab of pain and she crouched over, a whimper escaping through her mouth. But the man did not seem to hear or see. The questions continued to roll off his tongue mechanically, as if he were reading from a list he had been given but knew nothing about. There was aggressiveness in his voice that stemmed from the deep and dangerous boredom of an interrogator who had grown tired of his own questions.

The room was very hot. Under the coarse layers of her manteau and chador, Azar's body was soaked in sweat. The man asked her the date of her husband's arrest. She told him that and whom she knew and whom she didn't. Her voice throbbed with agony as waves of pain blazed through her. I must keep calm, she told herself. I mustn't make the baby suffer. She shook her head against the image that continued to crop up in her mind: that of a child, her child, deformed, broken, a sight of irreversible agony. Like the children of Biafra. She gave a grunt. Sweat trickled down her back.

Where were the meetings? the man asked. How many of them attended each meeting? As she gripped the chair against the fresh all-encompassing stabs of pain, Azar tried to remember all the right answers. All the answers she had given from one interrogation to the next. Not a date, not a name, not a piece of information or lack of it should differ. She knew why she was here, why they had thought that now was the perfect time to interrogate her, to get at her. Keep calm, she repeated to herself while she answered. As she omitted names, dates, places, meetings, she tried to remain calm by imagining her baby's feet, hands, knees, the shape of the eyes, the color. Another wave of pain soared and crashed inside her. She writhed, shocked at its ferocity. It was pain she had never thought possible. She was losing herself to it. Fingers, knuckles, nostrils, earlobes, neck.

Where did she print the leaflets? She heard the man repeat the question. She tried to answer, but the contractions seemed to be swallowing her, not giving her a chance to speak. She lurched forward, grabbing the table in front of her. She heard herself moan. Belly button, black hair, curve of the chin. She took a deep breath. She felt like she was going to faint. She bit her tongue. She bit her lips. She could taste the blood blending into her saliva. She bit into her whitened knuckles.

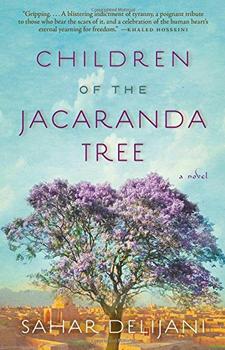

Excerpted from Children of the Jacaranda Tree by Sahar Delijani. Copyright © 2013 by Sahar Delijani. Excerpted by permission of Atria Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.