Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

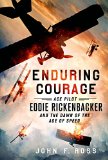

Ace Pilot Eddie Rickenbacker and the Dawn of the Age of Speed

by John F. Ross

The year that Eddie climbed onto that glistening Ford, an obscure German-born scientist named Albert Einstein had advanced his special theory of relativity, which would burst out its profound practical consequences before midcentury. The ripples of this and other discoveries tore the fabric of society—and knocked down many traditional modes of living and working. Wassily Kandinsky executed his first abstract painting, Picture with a Circle, in 1911, and that same year Cubism emerged. Virginia Woolf claimed that “human character changed” in 1910, as modernity itself was born and novels shook off their Victorian crinolines and experimented wildly in form. Syncopated jazz and ragtime rhythms introduced new tempos. Early Hollywood films, shot at sixteen frames a second but shown in theaters at twenty-four frames a second, showed their actors racing along in hyperfast apparent motion, frantic to get to wherever they were going at superhuman speeds. Pocket watches, once owned only by train conductors and the rich, became suddenly cheap and generally available. For the first time, people began systematically to mark time in increments of five and ten minutes.

Yet there is a powerful case to be made that no invention would propel the twentieth century forward with greater force than the newly configured internal combustion engine, which would power its first practical car in 1895 and make sustained, heavier-than-air flight possible only eight years later. These new technologies captivated the nation’s imagination as they burst cometlike into American life. Within a few short years of Ford’s introduction of the Model T in 1908, the chance to control, exercise, and enjoy speed passed into the eager hands of hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans. Seated behind his wheel, a driver effortlessly multiplied choice as well as speed. For the first time in history, multitudes without specialized skills could operate a machine regularly capable of outdistancing the fastest stallion. Nor did the driver have to interact with a creature with its own mind, which might decide to pull up midstride or even pitch its rider. Speed was now tamable to a whole host of new purposes.

Drivers related breathlessly how the countryside dissolved into an Impressionist blur as they rattled down even terrible roads; this would prove just the first taste of the new perspectives that individual high-speed mobility would bring America. It wasn’t only the thrill of high velocity but the feeling of being lifted by the rush of acceleration itself, as well as the mild g-forces that pressed the body at turns, even the mystery of swift deceleration. While the experience of flying itself would remain out of most people’s reach for decades, the increasingly more common sight of men soaring among and above the birds dissolved whole categories of the impossible.

“The world loves speed,” wrote a journalist in 1902. “All mankind would in some form indulge in it, if it but could. He who cannot, finds zest in watching him who can and does indulge … The love of speed is inherent and increasing in intensity. The automobile is spreading and will continue to spread the desire for swift and exhilarating flight through space.” Tasting the excitement of speed regularly—being able to divert it, revel in it, and put it to astonishing use—Americans would break open new horizons. The frontier lay not beyond the forest or across the river but at the end of a clutch. Nothing had ever quite so intoxicated the nation.

When Eddie climbed into that nearly prototypical Ford, there was no Indy 500 or NASCAR; there were no hot-rodding clubs or drag-racing cliques. Not one single person had water-skied, let alone gone out on a Jet Ski. The notion of doing everything much faster began to pervade all aspects of American life. It was happening in surgery and radio, and very soon on the edge of war. Zipping into the American lexicon would be new words that would communicate previously unimagined realities: zoom, rpm, mph, revving, and redline. Beyond that stretched new reaches of car-possibilities: car camping, drive-in movies, road trips, cruising the strip, Route 66 and the interstates, rest stops, suburban commuting, tailgating, and soccer moms.

Excerpted from Enduring Courage by John F Ross. Copyright © 2014 by John F Ross. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.