Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

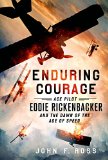

Ace Pilot Eddie Rickenbacker and the Dawn of the Age of Speed

by John F. Ross

The following morning Eddie left with the other children, but instead of going to school he walked over to the Federal Glass Factory, where his brother Bill had once worked. After inflating his age to fourteen and lying that he had finished eighth grade—a requirement of Ohio’s otherwise rudimentary child-labor laws—he was hired to start that evening, a twelve-hour night shift carrying freshly blown tumblers to the ovens on heavy steel platters. He walked two miles home and quickly overcame his mother’s objections. Weeks later, when a truant officer visited the house, Lizzie walked the man upstairs, where they peered in on the boy collapsed fast asleep on his bed, still wearing his grimy work clothes. Aware of the family’s difficulties, the officer finessed his report. Years later, an interviewer asked Eddie whether his elder brother had felt any resistance toward his taking the lead as the family’s breadwinner. Bill was industrious, conceded Eddie dispassionately, but he just didn’t have the same “push.”

Years before mandatory high school institutionalized adolescence, it was far from unusual for children to enter the workplace. Neither the Wright brothers nor Thomas Edison graduated from high school. The word “adolescence” itself had only recently entered the lexicon, and the cult of the teenager, hastened by the mobility conferred first by the bicycle, then by the automobile, would not blossom for some time. Even so, there was something eerily foretelling about a boy who could will himself from childhood to adulthood overnight, from rambunctious troublemaking to full-blown responsibility. Never again did he feel the pull of his friends in the Horsehead Gang, which quickly dissolved without his leadership. It was as if he just skipped adolescence entirely—and missed that often difficult period when young people become so painfully aware of what others think of them. He grew a thick skin. He learned to survive by taking command, focusing on the task at hand. In this new role, Eddie had no time for the anger that had become his father’s Achilles’ heel, nor for emotion of any sort. Much later a close friend would characterize him as “completely undemonstrative,” while Eddie’s wife recalled his “emotional shyness.” He never said nice things to her—“the words would choke in his throat”—although he did say flattering things about her to others when she wasn’t around. It’s not that he didn’t have feelings, but he buried them, because they were vulnerabilities that could compromise the imperative to survive. He would become a man whom people automatically called by his first name the minute they met him but whom few, if any, really got to know.

The sudden death of a parent rarely energizes a child; it is taboo for him or her to express even the most justified feelings of liberation in the wake of so profound a tragedy. Eddie, however, seemed only to relish his new freedom. Over the next two years, he would prove far more adept in the workplace than his father ever had—at the glass factory, then as a molder for the Buckeye Steel Castings Company, a bottle capper in a brewery, and a cobbler. At Goodman’s Shoe Company on West Broad Street, he stamped out heel-shaped pieces of leather, then laboriously nailed one piece to another, and another, to build a heel. Tired of this sleepwalking routine, Eddie fashioned a wooden heel template to save time by stacking three or four pieces, then nailing them together. The supervisor noticed and congratulated him.

He came to feel a strong confidence in his abilities, which, tempered by a precocious ability not to take offense or indulge in self-pity, ripened into an earnest industriousness that employers came rapidly to value. Carving marble at a monument works yielded praise from his boss and the skills to craft his father’s tombstone. His mother still ruled the house, though, and pulled him off the job after he developed an itchy throat and slight cough from the dust. It was an index of his growing manual talents and overall competence that the shop’s owner offered to double his salary on the spot, but his mother refused to let him compromise his health. Still, money was somehow coming in; with the help of his siblings, the family not only paid off the mortgage but fixed up the little house and yard.

Excerpted from Enduring Courage by John F Ross. Copyright © 2014 by John F Ross. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Be careful about reading health books. You may die of a misprint.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.