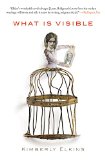

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Prologue

Laura, 1888

How little they trot me out for show these days, and yet here I am this frigid morning, brought down from my room to meet a child, and me not out of my sickbed two weeks. They're actually calling her "the second Laura Bridgman." The second, and I'm still here! What am I supposed to do, bow down to her? Set her on my knee? I didn't like children even when I was one, and now I think them worse than dogs. I've shriveled and so they've searched for another freak in bloom to exhibit and experiment on. It's taken Perkins decades to find one pretty enough, quick enough. Well, pretty is really the important thing, or at least not too strange or looking like what she is. Not looking like what I am.

"Just talk to her," Annie Sullivan writes upon my hand. "You have so much in common." Like two in the throes of the plague might share tips and grievances? Yes, little Miss Keller and I will rattle on about our lives in our respective cells, and since I can't taste or smell either—she's got that on me—she can tell me how the succor of roast mutton and strawberries and the odor of feces and chrysanthemums have opened enormous windows of happiness and universal feeling that I will never enjoy.

She curtsies, I feel the whoosh of her skirts as she goes down, and then she is on me, too excited for them to hold her back, if they are even trying. Her hair is heartbreakingly soft—I had forgotten this about children, this wonder—and her face round and warm as a meat pie against my leg, clutching at my dress, reaching for my hands. Too much! I raise both arms into the air. Annie always had bad manners, so this assault is no surprise. In the years she shared my cottage here, she acted the queen since she had partial sight, but really she was dirty Irish straight from the almshouse. After everything, though, I do miss Annie greatly, and she's done better than all right, it seems, as the teacher of this one. I taught Annie the manual alphabet, the finger spelling tapped out into the hand that is the only way to communicate with me and with Helen. Will she give me that credit, I wonder. And though Dr. Howe, Perkins' director, disavowed Braille, Annie says she is trying it with her charge.

The girl steps hard on my foot, right on the big toe that is bent with the rheumatism. "Get her off!" I rap into Annie's hand, and Helen is pulled back. We all breathe for a moment, and Annie takes the chance at last to greet me properly.

"Dear Laura," she writes, "you look well." Proof of her halfblindness right there!

"God tells me you are splendid also." She is no fan of religion, Miss Sullivan; that will get her goat. "Congratulations on your work with this?"

And then the little hand taps again at mine, insistent as a summer fly. "Thank you for doll. I love very much."

She is difficult to follow. "You're welcome."

"I'm almost nine. How old?"

What cheek to ask a lady her age, but then again, with my fame, it's no secret. "Fifty-eight." I try to walk away from her toward the heat from the window, but she grabs at my skirt.

"Please talk to me," she writes. "Please."

My presumptive heir is begging in my palm. And so I ask Helen my favorite question: "If you could have one sense back, which would it be?"

Her fingers go round and round in circles, and I can feel the girl actually thinking in my palm.

"Which do you pick?" she asks.

Though I have been deprived of all senses save touch since the age of two, while she is only deaf and blind, for me the choice is simple. "Sight," I tell her, all the glorious colors God has painted on lands and faces. Green is the color I remember with the most pleasure: green from the grass outside our house in New Hampshire. Blue still spills from that square of sky visible over the bed where I lay ill for almost a year, and Mama says my eyes were bright blue before they shrunk behind my lids. Red I have a strong and disagreeable sense of, from when they bled me with leeches. And black, black I know the longest and best because it is my constant companion. These are the only colors I can recall or imagine with any clarity.

From the book What Is Visible: A Novel. Copyright (c) 2014 by Kimberly Elkins. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

If there is anything more dangerous to the life of the mind than having no independent commitment to ideas...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.