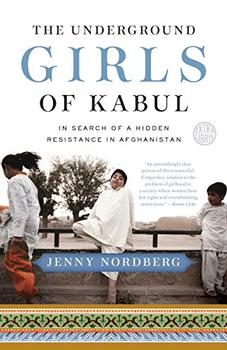

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In Search of a Hidden Resistance in Afghanistan

by Jenny Nordberg

Azita is one of few women with a voice, but to many, she remains a provocation, since her life is different from that of most women in Afghanistan and a threat to those who subjugate them. In her words: "If you go to the remote areas of Afghanistan, you will see nothing has changed in women's lives. They are still like servants. Like animals. We have a long time before the woman is considered a human in this society."

Azita pushes her emerald green head scarf back to reveal a short black ponytail, and rubs her hair. I shake off my scarf, too, and let it fall down on my neck. She looks at me for a moment, where we sit in her bedroom. "I never want my daughters to suffer in the ways I have suffered. I had to kill many of my dreams. I have four daughters. I am very happy for that."

Four daughters. Only four daughters? What is going on in this family? I hold my breath for a moment, hoping Azita will take the lead and help me understand.

And she does.

"Would you like to see our family album?"

We move back into the living room, where she pulls out two albums from under a rickety little desk. The children look at these photos often. They tell the story of how Azita's family came to be.

First: a series of shots from Azita's engagement party in the summer of 1997. Azita's first cousin, whom she is to marry, is young and lanky. On his face, small patches of hair are still struggling to meet in the middle as a full beard; a requirement under Taliban rule at that time. The fiancé wears a turban and a brown wool vest over a traditional white peran tonban—a long shirt and loose pants. None of the one hundred or so guests are smiling. By Afghan standards, where a party can number more than a thousand, it was a small and unimpressive gathering. It is a snapshot of the city meeting the village. Azita is the elite-educated daughter of a Kabul University professor. Her husband-to-be: the illiterate son of a farmer.

A few staged moments are captured. The fiancé attempts to feed his future wife some of the pink and yellow cake. She turns her head away. At nineteen, Azita is a thinner and more serious version of her later self, in a cobalt blue silk caftan with rounded shoulder pads. Her fingernails have been painted a bright red to match crimson lips, set off by a white-powdered face that reads as a mask. Her hair is a hard, sprayed bird's nest. In another shot, her future husband offers her a celebratory goblet from which she is expected to drink. She stares into the camera. Her matte, powdery face is streaked with vertical lines running from dark brown eyes.

A few album pages later, the twins pose with Azita's mother, a woman with high cheekbones and a strong nose in a deeply lined face. Both Benafsha and Beheshta blow kisses onto their bibi-jan, who still lives with their grandfather in the northwest of Afghanistan. Soon, a third little girl makes her appearance in the photos. Middle sister Mehrangis has pigtails and a slightly rounder face. She poses next to the twin mini-Azitas, who suddenly look very grown up in their white ruffle dresses.

Azita flips the page: Nowruz, the Persian New Year, in 2005. Four little girls in cream-colored dresses. All ordered by size. The shortest has a bow in her hair. It is Mehran. Azita puts her finger on the picture. Without looking up, she says: "You know my youngest is also a girl, yes? We dress her like a boy."

I glance in the direction of Mehran, who has been skidding around the periphery as we have talked. She has hopped into another chair and is talking to the plastic figurine again.

"They gossip about my family. When you have no sons, it is a big missing, and everyone feels sad for you."

Azita says this as if it is a simple explanation.

Having at least one son is mandatory for good standing and reputation here. A family is not only incomplete without one; in a country lacking rule of law, it is also seen as weak and vulnerable. So it is incumbent upon every married woman to quickly bear a son–it is her absolute purpose in life, and if she does not fulfill it, there is clearly something wrong with her in the eyes of others. She could be dismissed as a dokhtar zai, or "she who only brings daughters." Still, this is not as grave an insult as what an entirely childless woman could be called—a sanda or khoshk, meaning "dry" in Dari. But a woman who cannot birth a son in a patrilineal culture is—in the eyes of society and often herself—fundamentally flawed.

Excerpted from The Underground Girls of Kabul by Jenny Nordberg. Copyright © 2014 by Jenny Nordberg. Excerpted by permission of Crown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some to be chewed on and digested.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.