Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The convent was so narrow that it looked to have been built in an alley, crushed up against the houses on either side like a drunken crone held up by two fat fellows. Ours was the oldest house on the lane, the houses that had once stood on either side having been burned down, or torn down to make room for the new ones. Because the house couldn't spread out, it reached up; there were five floors, if you counted the cellar, and all the rooms were full, though the bodies in them changed about. My whole life, we never had a spare room for more than a day.

In our house we went to bed when the whole world was rising. I'd lie there and listen to the milkmaid shouting in the lane, and the women calling to those below to look out, as they emptied their pots. I'd fall asleep with the sun pinking the dark behind my eyes. I always thought it the best way to live; in daylight the world was merry and safe. At night it was always better to be up and ready. I'd no choice in it, so it was well that I thought it so fine—Ma would never have stomached me creeping about the house in the daylight, while all the house was abed.

Sleeping all day as we did, we took our breakfast when other folks had dinner, at three or four o'clock. The kitchen table had been built just where it was and took up near the whole room; you'd have had to chop it to firewood to get it out of the door. We sat around it, pressed together on the benches, the misses in their silks, all bare arms and bosoms, and Dora and I always pushed to the ends of the bench, with half our arses hanging off. The bullies would put heavy bars across the front door and come to sit with us, though sometimes they stood, the room being so full. There were chairs at the head and the foot, and the bullies never did sit in them, as the men might expect to in any usual house. Ma sat always at the head of the table. The other chair was for whichever girl she saw fit to reward, whether it be a miss who'd taken good earnings the night before or a newcomer who was proving difficult to turn and so needed softening.

When Dora and I weren't making ourselves useful we'd be huddled in the garret in the bed we shared, or else out upon the street, teasing the pigs; there were always pigs upon our street, let out and brought back in at night. Sometimes we'd be sent to the tavern around the corner, on Frog Lane, which hired out rooms to misses, to fetch home one of the girls. Our mollies were put two to a room at the convent, so one or other of them was always using the rooms at The Hatchet Inn. I preferred that errand over any other. I liked the smells: ale, straw, and smoke. The folks there knew my name and called out, "How d'you fare, little Ruth?" and best of all was the yard, with its roped stage, upon which there had been so many bouts between pugs, or cocks, or dogs, that the boards were patched black with old blood. I always lingered as long as I dared when Ma sent me there.

If you were a caller at the convent on a usual day, you'd think it as fine as any swell's place, with velvet hangings and sconces for candles upon the walls. The front stairs were always lit and the parlour, where the cullies sat, had a brocaded settee and a table with curved legs that looked ready to drop a curtsey. The parlour always had about it an air of waiting: all those breaths of restless old goats, waiting for a miss to have done with his crony and come to fetch him for his turn. None of the family ever would sit in that room, though it was done out so nice. If no sailor was waiting there, and if I thought no one would miss me, I sometimes went in to look at the pictures upon the walls. One was a small painting of a little girl, all done up in mourning dress, her face very serious and drear. The other was a fine picture of trees upon an autumn lane, made all from feathers. Ma had taken them from some likely lad by way of payment. I had a special fancy for the painting of the girl. I'd pose before the glass and with my hands clasped under my chin, as she did. I never could make my eyes like hers, no matter how I turned my head. Her eyes were sweet and mournful; mine were a pig's, too small for my face. Sometimes, I used to imagine the little girl stepping from her frame and strolling off down the autumn lane, perhaps to some place where she needn't look so sad.

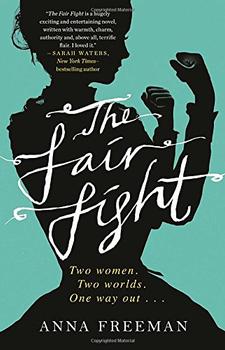

Reprinted from The Fair Fight by Anna Freeman by arrangement with Riverhead Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, Copyright © 2015 by Anna Freeman.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.