Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

It was a Sunday, but we had not gone to church that morning on account of the coming raid. The night before, the radios had announced that enemy planes would once more be on the offensive, for the next couple of days at least. It was best for anyone with any sort of common sense to stay home, Papa said. Mama agreed.

Not far from me in the parlor, Papa sat at his desk, hunched over, his elbows on his thighs, his head resting on his fisted hands. The scent of Mama's fried akara, all the way from the kitchen, was bursting into the parlor air.

Papa sat with his forehead furrowed and his nose pinched, as if the sweet and spicy scent of the akara had somehow become a foul odor in the air. Next to him, his radio-gramophone. In front of him, a pile of newspapers.

Early that morning, he had listened to the radio with its volume turned up high, as if he were hard of hearing. He had listened intently as all the voices spilled out from Radio Biafra. Even when Mama had come and asked him to turn it down, that the thing was disturbing her peace, that not everybody wanted to be reminded at every moment of the day that the country was falling apart, still he had listened to it as loudly as it would sound.

But now the radio sat with its volume so low that all that could be heard from it was a thin static sound, a little like the scratching of skin.

Until the war came, Papa looked only lovingly at the radio-gramophone. He cherished it the way things that matter to us are cherished: Bibles and old photos, water and air. It was, after all, the same radio-gramophone passed down to him from his father, who had died the year I was born. All the grandparents had then followed Papa's father's lead? - the next year, Papa's mother passed; and the year after, and the one after that, Mama lost both her parents. Papa and Mama were only children, no siblings, which they liked to say was one of the reasons they cherished each other: that they were, aside from me, the only family they had left.

But gone were the days of his looking lovingly at the radio-gramophone. That particular afternoon, he sat glaring at the bulky box of a thing.

He turned to the stack of newspapers that sat above his drawing paper: about a month's worth of the Daily Times, their pages wrinkled at the corners and the sides. He picked one up and began flipping through the pages, still with that worried look on his face.

I went up to him at his desk, stood so close to him that I could not help but take in the smell of his Morgan's hair pomade, the one in the yellow and red tin-capped container, which always reminded me of medicine. If only the war were some sort of illness, if only all that was needed was a little medicine.

He replaced the newspaper he was reading on the pile. On that topmost front page were the words SAVE US. Underneath the words, a photograph of a child with an inflated belly held up by limbs as thin as rails: a kwashiorkor child, a girl who looked as if she could have been my age.

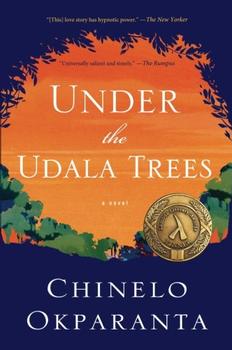

Excerpted from Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta. Copyright © 2015 by Chinelo Okparanta. Excerpted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When an old man dies, a library burns to the ground.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.