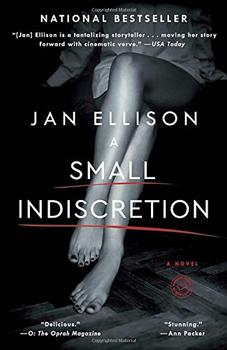

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Jan EllisonExcerpt

A Small Indiscretion

London, the year I turned twenty.

I wore a winter coat, the first I'd ever owned—a man's coat purchased at a secondhand store. I wore it every day, along with a silk scarf tied around my neck, imagining I looked arty or sophisticated. Each scarf cost a pound, and I bought them from an Indian woman who kept a stall in the tube station at Victoria, where I caught my train to work. They were thin, crinkled things, not the sort of scarves that ought to be worn to work in an office or that offered any protection against the cold. But I could not resist them, their weightlessness and soft, faint colors. The money I spent on them, and the habit I adopted of wearing a different one each day, seems to me now a haphazard indulgence, an attempt to prove that I was the kind of girl capable of throwing herself headlong into an affair with her boss—a married man twice her age—and escaping without consequence.

"Church," he said, the morning I arrived at the address the woman at the agency had printed out on a card. "Malcolm Church."

He extended his hand, and right away I was struck by a certain contradiction in him—the impressive height and mass of him in opposition to his stooped shoulders, his hesitant manner, his unwieldy arms and legs. He had a square face and round brown eyes and brown hair streaked with gray, but his features were mostly overwhelmed by his size, so that all I remembered afterward was the pleasing sensation of feeling small, by comparison, even at five feet eight. He had a strange way of talking, his head tucked into his neck and his eyes fixed in the empty space beyond, as if something were suspended there, ripe fruit or a glimmer of light, as if he were not quite brave enough, or perhaps too polite, to look a person in the eye.

He asked me how long I was available. I told him I planned to be in London three months, but that my work permit was good for six, through March of next year. I'd intended to claim I was available indefinitely, since the position was listed as full-time permanent, and I was entirely out of money and badly needed the job, but something had stopped me. Not a sense of right and wrong or fear of getting caught, but a hard center of self-importance I had not lived long enough to shed, the notion that I would offer myself on my own terms or not at all. And I was buoyed up by my typing speed—eighty words per minute—about which he never even inquired.

"That'll be fine," Malcolm said, staring intently over my shoulder as he proceeded to explain that his work was in structural engineering, and that he was currently preparing a bid for the new Docklands Light Rail station at Canary Wharf. The London Docklands, he explained, was an area in east and southeast London whose docks had once been part of the Port of London. The area had fallen into disarray, and in the seventies, the government had put forward plans for commercial and residential redevelopment. Malcolm had been involved in the early phases of the project. Now he was hoping to work on the renovation of the original rail station.

There would be dictation and word processing, he said, a little research and generally helping to set up the office and assemble the bid. The office was a single room upstairs from a sandwich shop near Bond Street, with two desks, industrial gray carpet and two folding metal chairs. On one desk was an unusual photograph of a woman and a baby, a posed black-and-white image with a startling play of silver light and shadow set against a background of trees and sky. A single smudge of pink had been hand-painted over the baby's lips. It was Malcolm's family—his wife, Louise, who would feature so prominently in my thoughts, and their infant daughter, Daisy, who was by then ten years old and away at the boarding school in the north that Louise had attended when she was Daisy's age. I was to learn later that the photograph had been taken by a young man named Patrick Ardghal, the son of an old family friend of Malcolm's, who was living in the cottage out back of Malcolm and Louise's house in Richmond. He'd taken the photo a decade earlier, when he was in art school.

Excerpted from A Small Indiscretion by Jan Ellison. Copyright © 2015 by Jan Ellison. Excerpted by permission of Random House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I have lost all sense of home, having moved about so much. It means to me now only that place where the books are ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.