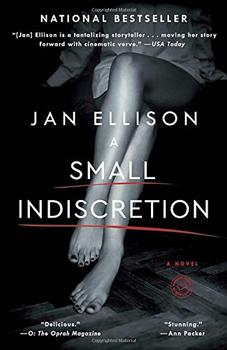

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Discuss | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Jan Ellison

In the photo Louise had blond hair and a fine straight nose and a smile with a hint of impatience in it, perhaps not with the baby per se, but with the general condition of motherhood into which Louise had finally plunged. It had taken them seven years to conceive their daughter, Malcolm told me later. By the time they became parents they had already been married a decade, and Louise had not wanted another child. She didn't have the temperament for it, Malcolm said. It overwhelmed and exhausted her and the delivery had nearly killed her, the baby, Daisy, having inherited from her father a rather large head.

I moved from a youth hostel in Earl's Court to a boardinghouse in Victoria. The building was five stories high, made of gray stone, on a block not far from the tube station. My room was ten feet square with bright-blue walls, a laminate desk and a hard, narrow bed covered in a thin white spread. There were bathrooms down the hall. There were no showers, only a single tub and a hose you attached to the faucet for washing your hair. There was no lock on the room with the bathtub, so I made a habit of propping a chair in front of the door for privacy. The chair, as I recall, did not stop Patrick Ardghal. Nothing much stopped Patrick when he had an idea in his mind. He simply shoved the door hard, and I welcomed him, I suppose, as I always did, and he undressed and climbed in. Our wet bodies were awkwardly entangled long enough to please him—then he left, as he always did, taking my heart with him.

My rent was sixty pounds a week, including breakfast and dinner. The meals were served buffet-style in the dining room downstairs. There were eggs and toast and stewed tomatoes for breakfast, meat pie or fish and chips or baked ham for dinner. It was a source of solidarity among the other boarders to complain about the food but I could not in good conscience join in. I loved those meals, the bounty and efficiency of them, the thick gravies, the custards and puddings and soft, fat rolls. It seemed a small miracle to me, to have so much available and to be paying for it all with my own wages. It pleased me, too, each time I handed over a pound coin in exchange for a scarf, and when I purchased, at the secondhand shop in Notting Hill, the winter coat, a full-length single-breasted gray tweed with covered buttons and a wide collar that could be turned up against the cold. I wore my coat and scarf and descended the escalator into the bowels of Victoria Station, emerging again into the dense, unyielding energy of city life feeling brisk, and stylish, and superior to the person I'd been when I'd left home. I was taken over by a sense of liberation and possibility. Any false steps I made now would be mine alone. Any foolish moves would be private business that had no bearing on the hopes and dreams of others, and that would not later be a source of remorse or reckoning or pain.

•••

What a shock to discover, some twenty years later, that exactly the opposite was true. To learn, in the aftermath, that I hadn't known the half of it. To stand in my San Francisco kitchen last June and slip my finger through the flap of a white envelope, and to find a black-and-white photograph of myself in that tweed coat, standing on the chalk down of the White Cliffs of Dover, waiting to board a ferry to Paris.

It was a photograph innocent enough to anyone unacquainted with its history, its treacherous biological imperatives, its call for reparations left unpaid. It had been solarized, just as the photo of Louise and the baby on Malcolm's desk had been. It had been subjected to a light source in the darkroom, causing a reversal of dark and light. My form, and Malcolm's, along with the inch of air between us, were bathed in silver light that brightened at the edges like a halo. Louise and Patrick, on the other side of the photo, were deep in shadow. The scarf I was wearing had been hand-colored a blunt red. It was tied around my neck like a choker, like a noose. But it wasn't me who was about to hang.

Excerpted from A Small Indiscretion by Jan Ellison. Copyright © 2015 by Jan Ellison. Excerpted by permission of Random House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The low brow and the high brow

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.