Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

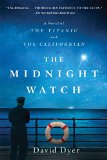

A Novel of the Titanic and the Californian

by David Dyer

But when we arrived home we saw that the family chickens had been slaughtered in their pens. They lay in the mud featherless and mutilated. Harriet – who had tended these birds, given them names and collected their eggs – slipped her quivering hand into mine.

As we climbed the stairs we heard rhythmic clapping and the singing of songs in Spanish. I held Harriet's hand tight and opened the door. The mosquito nets had been removed from the windows and candles placed on the sills. A makeshift altar of taller candles had been built on the floor, around which local women – half a dozen or so, all dressed in white – sat on boxes. When they saw us they sang and clapped louder, rocking back and forth.

In the centre of the room, on the floor near the altar, sat my wife. Perhaps she had drunk liquor, because she did not seem to notice us. Harriet began to cry. At first I did not know why, but then I saw. Her mother was holding thin hemp strings that ran up to the ceiling through a crude system of blocks and pulleys. I followed the strings upwards and there, suspended from the central beam, was the body of my son. He too was dressed in white, and was covered in feathers. Bird wings, still bloody, were attached to his shoulders and they opened and closed as my wife pulled the strings.

A woman came to Harriet, dabbed at her tears with a rag and said, in faltering English, 'No tears, no tears – tears wet the wings of the angel, he cannot fly to heaven.' The woman turned to me: my son was an innocente, she said, an angel baby. His place in heaven was certain, and there could be no greater happiness. No one must cry. The other women clapped and sang. 'Nada de lagrimas. Nada de lagrimas.' Olive joined in the clapping, applauding the dead little body creaking on its contraption of strings and pulleys.

It took only seconds for me to pull it all down. The women screamed; I felt one beating me hard on my back. I ignored them and held the tiny corpse in my arms. At first I was repulsed by this grotesque parody of my son – even after I tore away the feathers and bloodied wings, its strange, deadweight stiffness appalled me. But as I looked into the face I became mesmerised. His eyes were open and he peered out into the world with an unfocused stare, just as he had when he was born, seeming to see everything but nothing: so physically present but so absent too. There is something strange and profound in the gaze of the newly born and the newly dead. They seem able to see two worlds at once.

Olive tried to retrieve the baby from me but I pushed her away. She slapped me hard across the face and said she would not let me take him from her a second time. There was hot blood in my cheeks and stinging tears in my eyes, but my wife's face was blank and dry. Not then or ever after did I see her cry for our poor son.

'There is a better way,' I said, turning from her and carrying the small body outside to be washed by the rain.

I buried him on top of a green and gentle hill overlooking the lake. Harriet stood with me as I did so and said a quick prayer of goodbye. A week later we returned to Boston. Olive refused to speak to me about our son, but I showed her some brief sketches I'd made of him in words: the way his tiny fingers had curled tightly shut when she tickled his palm with her breath, how he was soothed by the smell of orange skins.

Over the following months I wrote of our son's life in more detail. I began, even, to extend it a little by envisaging his future. I published a small portrait of him in a Boston magazine in which he grew into a young boy who raced automobiles. Olive read my work, but she never forgave me. I might be able to convey something of a likeness of our son, she said, but I would never be able to show how much she had loved him. That was something beyond words.

In time I began to write about others who had died – at first, people I'd known personally, but then strangers too. I began to specialise in floods, fires and catastrophes. At the Boston American, where I worked, I became known as the Body Man. If there was a disaster, they would call me. I wrote about the sinking of the General Slocum, the Terra Cotta train wreck, the Great Chelsea Fire, and more. When I tried to report on commerce or politics, my writing lacked – well, the life of my body stories. The city editor said I should stick to what I did best, and so 'follow the bodies' became my motto.

Excerpted from The Midnight Watch by David Dyer. Copyright © 2016 by David Dyer. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.