Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

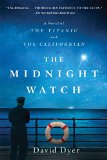

A Novel of the Titanic and the Californian

by David Dyer

But I want to say at the outset that I was never a ghoul. I respected the dead. I always sought out the truth of how they had died, and when I wrote about them I thought always of my own son and how much I loved him. I wanted to give the poor mangled bodies of this world a voice. I wanted to make them live again. My writing was an act of justice.

In 1911 I happened to be in New York when the Triangle Shirtwaist factory caught fire, killing nearly a hundred and fifty people, most of them young immigrant women. I saw the Asch Building ablaze at Washington Place and watched the girls jumping from the ninth and tenth floors. I saw five girls leap together from a window, their hair and dresses on fire. I saw another girl hang as long as she could from the brick sill until the flames touched her hands and she let go. I watched another stand at a window, throw out her pocket book, hat and coat, and step out into the cool evening air as calmly as if she were boarding a train.

When the bodies were taken to a ramshackle pier adjacent to the Bellevue Hospital I followed them. They were lined up in neat double rows, either side of the long dock, some in open boxes, others simply laid on the bare planking. I walked up and down. I said sorry on behalf of my country to those poor girls, who stared back at me in openeyed surprise, and I took notes. In the following weeks, I found out the truth of what happened to them. I told the world how Max Blanck, the factory's owner, had climbed a ladder to a building next door and left them to die. I brought the girls to life as best I could, publishing stories in Boston, New York and London. Like a courtroom sketch artist, I tried to capture their likenesses in a few finely observed strokes – a phrase here, a sentence there. It worked. People read my little portraits and felt the injustice of it all. They said such a thing must never happen again. At the Boston American the city editor passed a note to his juniors: 'If there are bodies, call Steadman.'

So when my telephone rang at two o'clock one Monday morning just over a year later, I knew it would be my newspaper and I knew there would be bodies. I wasn't disappointed. The duty editor told me an extraordinary thing: the new Titanic had struck ice and been seriously damaged. People may have been killed in the collision. The station at Cape Race had heard the ship calling for help. The duty editor assured me he was perfectly serious; it was not a joke.

I dressed quickly and walked the mile and a half from my apartment to the Boston American office. The streets were deserted. There was no moon and shreds of cold mist drifted in from the harbour like floating cobwebs. I could smell saltwater. In downtown Boston the North Atlantic always felt close and alive, but at this hour it seemed especially so. I thought about the Titanic out there somewhere, her bow crushed, crewmen caught in the mangled steel. I began to plan how I might get aboard when the ship limped into port.

When I arrived at the Washington Street office, Krupp, the city editor, was already there, shouting at newsboys and dictating cablegrams. Tickers clattered and telephone bells rang. As soon as he saw me Krupp told me to go downstairs and get hold of someone from White Star in New York on the long-distance line – preferably Philip Franklin himself. But the line was overloaded. The operator could not get me through. I tried instead to call Dan Byrne, my friend at Dow Jones, and then the Associated Press, but the lines were busy.

'Never mind about the telephone then,' Krupp said, interweaving his fingers so that his hands looked like a mechanical bird trying to take flight. 'Go down there, to New York, on the first train, and get it all from Franklin direct. There are bodies here, John, I can smell 'em.' He laughed at his own joke.

A couple of hours later, as streaks of pale grey began to lie along the horizon and a feeble crescent moon showed itself in the eastern sky, I boarded the train out of Boston for New York. Something told me that Krupp was right: there was a good body story for me here. I felt a tingling energy in my fingers, as though they were already beginning to write it.

Excerpted from The Midnight Watch by David Dyer. Copyright © 2016 by David Dyer. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Griffin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The worth of a book is to be measured by what you can carry away from it.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.