Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

You told me things about you, things that seemed irrelevant at the time, but that I recalled later in order to make better sense of our meeting. You said you had once built a fountain out of used water bottles and that, a few years ago, you had participated in a staged reading of Ulysses that had lasted one hundred and seventy-six hours. I found myself attempting to match the eccentricities of your stories and only coming up a little short, beginning with the story of my parents' confession, and how afterwards they never mentioned it again, and that I had never asked, because, in the way of children, I knew the subject had simultaneously been opened and closed.

You had recently dropped out of a doctoral programme in Philosophy. Why, I asked, and you told me, as if you were realising something only at that very moment, that it was no longer important to you. What would you do? You weren't sure. You might travel, see something of the world. Or you might practise the piano for a few years. You seemed very sure of yourself, in the way you held yourself and carefully paused before you spoke, and yet the things you told me betrayed a man with little ambition or certainty, a man with nothing to push against and hence adrift in a sea of infinite choices.

When I looked around, I saw that we were the only two people left. I was about to suggest we go somewhere else and decided instead that we should wait until the café closed and we were forced to leave. Your gaze was still fixed on me and I shifted in my seat. You seemed comfortable with pauses in the conversation but I needed to fill the silence, so I told you about the dig. 'I'm going to Pakistan next week,' I said. 'I'm going to dig out a whale fossil.' I told you that I was joining an expedition to find the bones of Ambulocetus natans, the walking whale. 'We're hoping to bring an entire skeleton back. The pelvis will tell us a lot.' I matched my pace to yours. Every word came out slow and deliberate. The word 'pelvis' sent a charge through me.

I asked about your family, and you told me the kind of story I had never heard before, that is, the story of perfect American people. Parents both professors at Harvard, now divorced but still great friends, three brothers and a younger sister, a house in Porter Square, a grand piano in the living room, lemonade in the refrigerator, a kitchen that smelled of wood and chamomile (the last details made up, but close to reality, as I would soon discover). No wonder you were lost. With nothing to resist, you floated like a fallen leaf. Then you said, 'My grandmother died last month. Every night I go to Sanders and I listen to the music. When there isn't anything at Sanders, I go to the Boston Philharmonic, and, sometimes, to the movies or to Shakespeare in the Park or to the Hatch Shell.' I reached out to touch your knuckle with my tea-cold hand. You seemed pleased by my touch, yet you didn't return the gesture. I told you that I had never been close to anyone who had died. Then I said: 'I know this will sound strange. But when I remembered my parents telling me I was adopted, it felt like a death. Like there's a person I've been my whole life and she's a fake, a ghost.'

'It must be hard, not knowing.'

'I'm afraid of what it means. And I feel alone in the world.'

'Loneliness is just part of being a person. We long for togetherness, for connection, and yet we're trapped in our own bodies. We want know the other fully, but we can't, we can only stretch out our hands and reach.'

It was so close to what I had felt an hour or two ago, when you had touched me and then untouched me, that I said, 'I think that's the best thing anyone has ever said to me,' and you smiled, your lips disappearing into your beard.

You said were pleased to have been given the opportunity to say the right thing. Then you asked me to tell you more about Dhaka. 'I don't know anyone from Bangladesh. In fact, I can't say I know any whale-hunting Shostakovich fans from any country.' I was charmed by this description of myself. I said you should come and see the place for yourself. You said you would like that. I told you how my parents had met during the Bangladesh War, that it had been the event that had framed their lives, and mine. We talked about that for a bit, and I gave you the potted history of my country I had narrated many times in the last seven years.

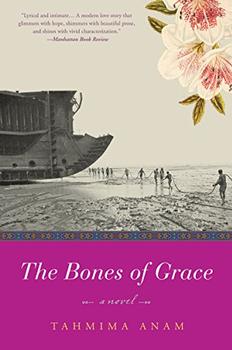

Excerpted from The Bones of Grace by Tahmima Anam. Copyright © 2016 by Tahmima Anam. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A few books well chosen, and well made use of, will be more profitable than a great confused Alexandrian library.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.