Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The café closed and we stepped out into the night, which was bright with heat and cones of streetlight. We drifted slowly towards my apartment. There seemed an infinite number of things left to say. We hesitated at the top of my street, reluctant to part, and, if I had paused to think for a moment, I may have had a premonition of what was to come: breaking your heart, finding my mother, Grace, the end and the beginning, the pulling crew, the discovery of love and its abandonment, and my telling you this story of our love, and of Anwar, and my mother. But I didn't pause, and the clairvoyant moment passed me by, and so we said an ordinary goodbye, promising to meet in the morning. When we parted, I felt my mind freeing itself of the story of my birth and turning to more graspable things, the dig I was about to go on, the fossil that was waiting in the earth, the lip balm and magazines I needed to buy before I departed.

You will wonder, as I often have, about the precise moment we fell in love. Was it on Grace, after you played the piano, or was it before that, the moment I saw you through the print-smudged glass at Chittagong Airport, or in your parents' living room, or as we parted that first evening, Shostakovich soaring in my music-mind, turning around as you walked away so that I could see you retreat with slow steps in your sandalled feet and hippy trousers?

But I should tell you now that it was not that night, because that night, I did not believe in love. I knew, of course, that it existed. I knew that it was the central principle around which most people built their lives, and I wasn't foolish enough to assume that it was something I could avoid entirely. But I did not believe that I lived in an age when a great love was possible. Everything about my life was too easy. I could love whomever I wanted, and marry or not marry them, or change my religion, or get divorced multiple times and have children with three different fathers if I wanted. I came from what you might call a traditional society, but I was not in thrall to that society. What I was in thrall to was the past. This had to do with my parents and the war they had been in, and, as a model for love, for what was possible between two people, they had set an example that fixed in my mind the notion that the epic thing, the one that went down in legend and song and was anointed with passion that lasted beyond beauty and youth, was something that only happened to other people, people that came before me or were born into magical, troubled times. I didn't believe that I was immune – of course I would love, and be loved – but I had proposed to myself a life that respected its historical moment and demanded something less, something tamer than those deeper furrows and interruptions of the heart.

As for you, if you had asked me, I wouldn't have been able to give you a single reason for your interest in me. I told myself this: (a) I would make an amusing anecdote for you later. Hey, you would tell yourself, I met this Bangladeshi palaeontologist and we listened to Shostakovich and then Nina Simone and she loves Anna Karenina. What're the odds? Or, (b) you felt sorry for me. Or, (c) you were actually a social outcast, totally unlikable and in desperate need of company, and I just couldn't see it. There was, of course, another option, which was that your interest in me was genuine – but I couldn't really fathom that, because I would have had to change my own understanding of myself and admit that I was what you were looking for, and that would have been beyond my imagination.

Now that my estimation of myself has taken a significant battering, I can say this: you did love me. You loved me from the very start. It could have been because you found me beautiful, or interesting, but more than that, it was because, although you bore none of the outward signs of being anything like me, we were, in fact, very similar. In me you saw embodied all the things you had felt about yourself: that you had been born into the wrong family, that there were things within you that had yet to be voiced and you might, if you were lucky, find yourself uttering them in my presence. In other words: we were nothing, yet everything alike. And you had the wisdom to see that from the start, even if I didn't.

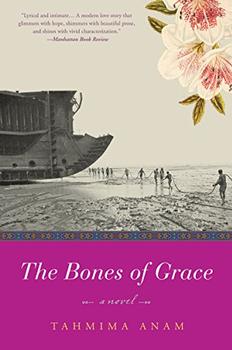

Excerpted from The Bones of Grace by Tahmima Anam. Copyright © 2016 by Tahmima Anam. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.