Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The American Revolution Through Painters' Eyes

by Paul Staiti

Peale's credentials as an accomplished artist were equally impressive: three years of study under Benjamin West, the distinguished American painter in London; dozens of portraits of Continental officers, many taken at camp-side; and artistic commissions from congressional leaders, including John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

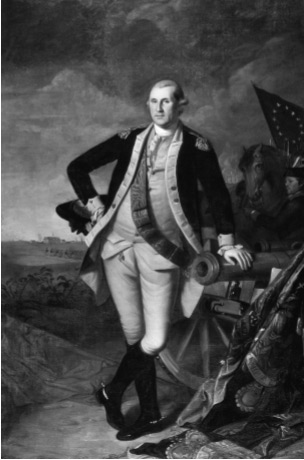

For the State House portrait, Washington made himself available to Peale for sittings between January 20 and February 2, 1779, at which point the general moved to his military headquarters in Middlebrook, New Jersey. Over the course of those two weeks Peale had to work on the eight-foot portrait at lightning speed.3 And he had to ask himself, and ask Washington, what the picture should show. The choices were endless. Washington might be depicted in the midst of a battle, and if so, there would be the question of which one. Or he could be seen far from the battlefield, perhaps at field headquarters, or appearing before Congress. There were ample reasons to portray him as a fearless warrior leading troops, but as compelling, he could simply be seen as an exceptional person.

Peale and Washington must have come to an agreement to focus on the decisive Battle of Princeton, which took place a week after the crossing of the Delaware and the Battle of Trenton. One of the most brutal scenes of combat during the Revolution, Princeton was fought on January 3, 1777, and it was won because Washington rallied the demoralized troops by coming to the front and then marching his horse directly into the line of fire. When it was over, the battle acquired special significance, not only because the British lost that day but also because it proved that their army was not invincible. Princeton was the first glimmer that the Revolution was winnable.

A decision also needed to be made on what aspects of Washington's character Peale should emphasize and what messages the portrait ought to broadcast. Since it would be put on display in a building at the heart of American independence, Peale needed to demonstrate the new concept of leadership in a republic. He did that by rejecting the climactic moment when Washington thrust himself into the battle, and emphasizing instead the aftermath of victory when Washington's inner qualities were most visible. Approachable, knowable, understated, calm, benevolent, and slightly ungainly, Peale's

Charles Willson Peale, George Washington at Princeton, 1779

Washington looks directly at his audience and comes across as a man of easygoing refinement and complete confidence.

After Peale put the finishing touches on the picture by traveling to Princeton to check the topography and review the architecture of Nassau Hall, he installed the huge portrait in a prominent place, behind the Speaker's chair in the State House, in majestic celebration of the great man of the new republic of virtue. It hung there until September 9, 1781, a Sunday, when Loyalists broke into the building and slashed it repeatedly with a knife. A Philadelphia weekly reported that "at night, a fit time for the Sons of Lucifer to perpetrate the deeds of darkness, one or more volunteers in the service of hell, broke into the State House in Philadelphia, and totally defaced the picture of His Excellency General Washington." Peale was called in to remove the picture and repair the damage, and over the next two weeks he cut away the damaged parts, patched in new canvas, and repainted those areas to match what had been there before.

Some of the Philadelphia public felt "indignation at such atrocious proceedings." But for the Loyalists, still in considerable numbers, slashing the picture must have been satisfying retribution for a cause that was lost, largely because of Washington. The painting had been left alone for two and a half years, during which time the fortunes of the war shifted back and forth. But when the picture was cut in the fall of 1781, during the siege of Yorktown, Britain's surrender was imminent and some of Philadelphia's Loyalists must have felt the need to strike back against the inevitable, at least in a symbolic way.

Excerpted from Of Arms and Artists by Paul Staiti. Copyright © 2016 by Paul Staiti. Excerpted by permission of Bloomsbury USA. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

At times, our own light goes out, and is rekindled by a spark from another person.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.