Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

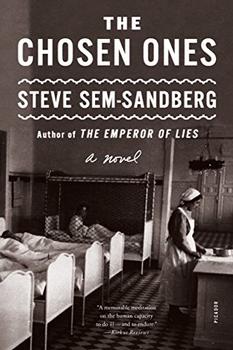

A Novel

by Steve Sem-Sandberg

Portrait of a Father Eugen Ziegler took a great deal of pride in his appearance. Before going to bed, he smeared nut oil into his strong, dark hair and kept it in place by pulling a ladies' stocking over his head. Whenever he might be coming to stay the night, Leonie always put a towel on the pillow to protect it from the oil. To Adrian, a towel on the pillow at bedtime meant that his father was on his way home. Though the towel on his father's pillow was often untouched, he remembers how hopeful he would feel every time and then how overwhelmingly disappointed, because his father was a great one for making generous promises about the special things he would bring next time he came home. A toy car, perhaps, or a steely marble or a collection of colourful bottle labels that he had showed Adrian once, promising that, next time, he'd have got hold of another collection just like it for his boy. Then next time, and the next and next again. At times, if and when his father did come home, it could be grim. He often arrived so late at night that Adrian was asleep and never heard the noise of the door slamming. In the morning, his mother was lying half on top Eugen's body as if she had tried to wrestle him down during the night or as if something inside her had broken and left her unable to move away on her own. Eugen Ziegler kept very quiet about himself and his relatives, which was strange for someone usually so cocksure and boastful. He had told Adrian that the name Ziegler had to do with his descent from one of the thousands of Czech labourers who had travelled to Wien to labour in the brick works – the Ziegelbrenners – without whom no houses could have been built in this city. Or so he said. Ziegler became his name because he was a Czech, and moulding and firing bricks was what the Czechs did. It didn't take Adrian long to realise that this was no more than a tale. Sometimes, his father would speak of his work as a handyman in a railway station somewhere in eastern Slovakia, and how he had just happened to get on a train to Donetsk in Ukraine where he got himself a job at a steel mill and stayed for years. The revolution had just ended and thousands volunteered to go to Russia because they were fired up by Lenin. I've always been a communist at heart, Eugen Ziegler would say, beating his breast. This was sheer bombast. Ziegler had no heart but reckoned he could get away with pretending that he did or, at least, that being so handsome would make up for the defect. As Auntie Magda kept saying, Eugen's looks made women turn their heads. Well, a certain kind of woman, Auntie Emilia would add. When Adrian asked her if his mother was one of these women, Auntie Emilia told him that Eugen had been different in those days. But if Adrian went on to ask more about what he had been like, in those days, the answers became vague and muddled because one wasn't to speak about what had been. Still, it was fact that Eugen Ziegler spoke Russian, so there might have been a grain of truth in the story about running off to Donetsk. Once, he and Adrian almost paid with their lives for his language skills. It happened in the autumn of 1939, just weeks after Eugen had collected Adrian from Mödling and they were planning to start a new life. They lived in the 3rd Bezirk, on Erdbergstrasse, which is only a few blocks away from Rochusmarkt. Every day, Eugen would go to the pub to negotiate business deals and, every night, his oldest son Adrian was told to go and walk him home. On the slow, unsteady way back to Erdbergstrasse, Eugen, who was usually dead-drunk, would go on about how Wien was no longer the city it once was, the streets were crawling with Piefkes, he said, traitors and Nazi swine, and, once, when he saw two of them in Wehrmacht uniforms on the square at Rochusmarkt, he swayingly pulled up in front of them and, before Adrian had time to react, let out a stream of Russian abuse, all presumably meaningless to the soldiers. What they did grasp was that this man spoke Russian. Spitzel, a fucking spy, Adrian heard one of them snarl as he whipped the rifle off his back. Adrian grabbed his father's arm and managed to drag him behind one of the remaining market stalls where they crouched, squeezed tightly together, and heard the two soldiers run past, rifles rattling against the buckles of their Sam Browns, the heels of their boots thumping on the cobbles, and then Eugen pulled his fingers through his hair and turned his face, stinking of alcoholic fumes, to Adrian and hissed:

Excerpted from The Chosen Ones by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Copyright © 2016 by Steve Sem-Sandberg. Excerpted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.